For years now, an epidemic of opioid overdoses has been sweeping across North America. According to the US Department of Health and Human Services, on an average day in the USA, more than 650,000 opioid prescriptions are dispensed, 3,900 people initiate non-medical use of prescription opioids, 580 people initiate heroin use, and 78 people die from an opioid-related overdose.

The devastation and loss of life has been unprecedented.

This is not a new phenomenon. The problem has been growing for at least two decades. But in the last few years, one particular drug has forced its way to the forefront of people’s minds when they think about the opioid crisis: fentanyl. This synthetic opioid is 100 times more potent than morphine, and is increasingly being found in heroin sold in the US and Canada. Its impact has been huge – in British Columbia and Alberta, two of the hardest hit Canadian provinces, overdose deaths linked to fentanyl rose from 42 in 2012 to 418 in 2015, a 10 fold increase.

In the US, drug overdoses killed more people – 52,404 – than car crashes in 2015, with synthetic opioid deaths (including those from fentanyl) rising a massive 73% to 9,580. It’s a crisis that is affecting the lives of everyone, from superstars like Prince – who was found dead at Paisley Park in April 2016 from a fentanyl overdose now believed to have been caused by counterfeit pills – to 14-year-old Chloe Kotval, an Ottawa schoolgirl who overdosed and died on Valentine’s Day this year.

Until now, the worst of the fentanyl crisis has been restricted to North America, but public health and drug policy experts have long cautioned that it would only be a matter of time before it reached UK shores. Sadly, the signs are that this time has now arrived. Spates of fentanyl related deaths have been reported around the country in recent weeks and months, prompting fears that the drug has now found its way into the UK’s heroin market, a hugely worrying development given the already record numbers of drug related deaths in the country.

Police forces in Yorkshire and Teeside have issued warnings after four people died in Barnsley, South Yorkshire, on Good Friday, followed by two more deaths the following day in Leeds and Normanton in West Yorkshire. These deaths came after six people died within days of each other in Stockton-upon-Tees in March, all of which were thought to be linked with what the police referred to as a batch of “low-grade” heroin, thought to contain fentanyl.

Earlier in the year, seven people died of overdoses in Hull, and although police have not yet confirmed whether these were fentanyl-related, West Yorkshire police are reported to have confirmed the presence of the drug there. A pattern is definitely emerging of clusters of deaths, suggesting that fentanyl contaminated heroin is entering the drug market, but isolated cases have also been reported.

27-year-old Ross Mallon’s body was found by his mother in the home they shared in Hampton Dene, Hereford, in January. Toxicology reports found that he had consumed a significant amount of fentanyl, along with diazepam, cocaine, and sertraline.

In November, 18-year-old Robert Fraser, from Deal in Kent, was found dead in his bedroom. Toxicology reports showed that he had taken fentanyl. Reports of his death in the press contained conflicting accounts – sometimes within the same article – of where the drug had come from, with some claiming it had been given to him for free by a drug dealer from whom Robert was buying cannabis, and others suggesting that it had been purchased from the ‘Dark Web.’ What is clear is that the prevalence of fentanyl in the UK is on the rise, with increasingly deadly results.

Tales of adulterated heroin in the UK have been around for years, but this new phenomenon is something very different. I spoke with Neil Woods, ex-undercover drugs officer, current Chairman of LEAP UK, and author of Good Cop Bad War, about the history of Britain’s heroin market and what the emergence of fentanyl tells us. “In the UK, heroin has traditionally been relatively unadulterated,” he explained, “despite claims of brick dust and strychnine and other such scares. It has traditionally and for many years been adulterated at the point of import with a mixture of caffeine and paracetamol. This combination behaves like heroin when smoked from foil, and the colouring matches. Hardly ever is there any further adulteration, as the demand is for a strong product.”

Asked why fentanyl-tainted heroin is emerging now, Neil was unequivocal about where the blame lays. “The average purity for heroin has steadily risen since the MoDA, apart from a glitch of low purity in 2009-2010 due to poppy blight. Now however, it is possible to get a stronger product that’s easier to smuggle, which follows the simple economic rule of prohibition. During the alcohol prohibition in the USA, no one could buy beer, because more money could be made from Whiskey. Well if heroin is beer, we are seeing the first signs of its whiskey. The black market does not care about the users, a spate of deaths are just normal business losses to them. It’s time for nation states to take responsibility by taking control of the commodity.”

The response to the fentanyl crisis in North America has been predictably slow and short-sighted, with one Democratic lawmaker just this month introducing a Bill to “keep fentanyl out of the United States.” The Bill would authorise $15 million dollars to be spent on new screening devices and laboratory equipment designed to detect fentanyl entering the US. It would seem that, even after decades of ever-rising death tolls, increased availability and purity of opioids, and billions of dollars spent, some Senators still feel that the best way to deal with the problem is to throw money at it and attempt to clamp down even harder.

Not all responses have been as ham-fisted as this, however, and effective harm reduction initiatives are gaining ground. Insite supervised injection facility in Vancouver, Canada, has provided a space for heroin users to inject their drug of choice under the watchful eye of medical professionals since 2003. Despite years of pushback from both the federal government and a minority of local citizens, the site’s effectiveness is now acknowledged, with plans now afoot to open three similar facilities in Toronto. In the US, supervised injection facilities are now planned in Seattle and Washington, whilst President Obama finally lifted the ban on federal funding for needle exchange programmes in 2016.

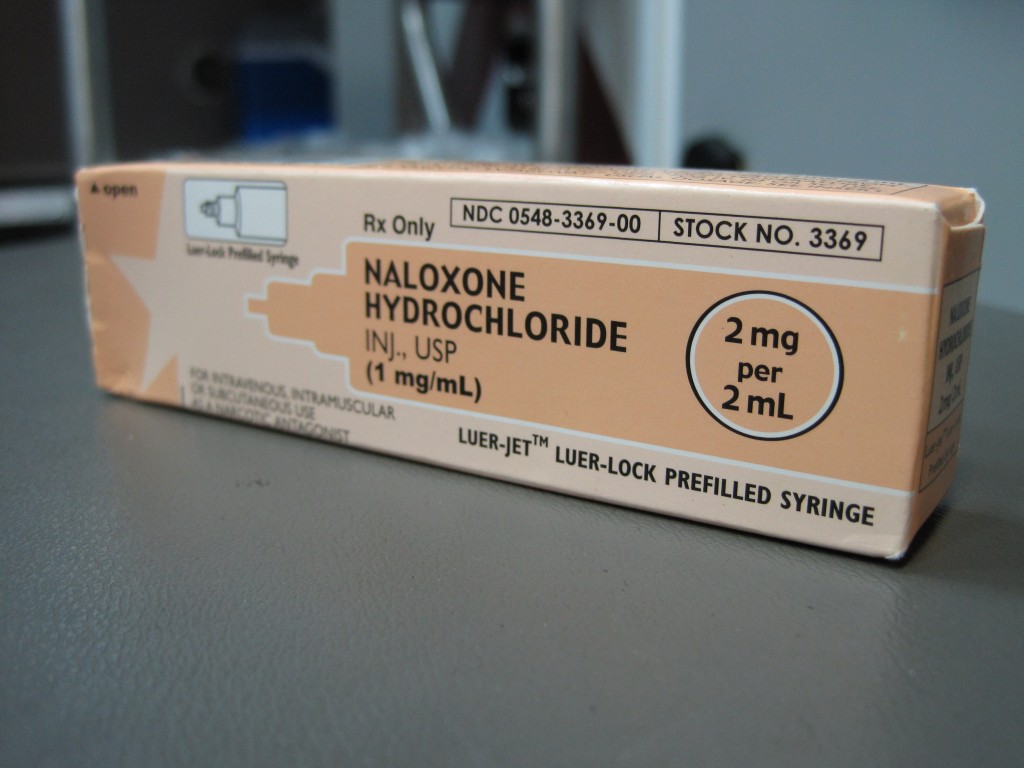

In addition, awareness and availability of Naloxone, the so-called “overdose antidote,” has steadily increased in recent years. The FDA approved Narcan nasal spray, the first nasal spray version of Naloxone, in the US in 2015, and by mid-2016, all but three states had passed legislation designed to improve access to Naloxone. The situation is still far from perfect – more widespread use of Naloxone would doubtless save many lives – but it is improving all the time. This month, New Mexico Governor Susana Martinez signed legislation – the first of its kind – that requires all state and local police to carry Naloxone, as well as requiring clinics to provide patients with two doses of the drug plus a prescription.

If the UK is to avoid the same fate as the US and Canada when it comes to fentanyl deaths, it is vital that the reaction to the problem is swift and effective. Much like in North America, overdose deaths in the UK have been on an upward trend for years, reaching record levels in 2015. The government simply does not have time to prevaricate on the question of harm reduction – if they do so, they will be responsible for ever greater numbers of preventable deaths.

Thankfully, as in the US, there has been plenty of talk surrounding the opening of supervised injection facilities – the first such site was given the green light in Glasgow last year – and in 2015 a change in UK law made it legal for Naloxone to be prescribed to anyone who is likely to encounter someone overdosing on heroin. However, despite these changes, funding for Naloxone is still at the discretion of local authorities whose funding has been drastically cut by successive governments.

Now that fentanyl has reached our shores, the situation is all the more desperate. It is vital that the government does more, quickly, to protect users. As promising – and welcome – as the opening of supervised injection facilities and spread of Naloxone use is, this response has been nowhere near enough even to cope with existing heroin overdoses. Should fentanyl’s presence in the drug market increase, any small gains made will doubtless be overwhelmed.

More supervised injection facilities need to be opened – despite ill-conceived claims that they only encourage drug use, the evidence is clear that they save lives and ultimately allow more users to quit or control their use – and more funding is needed for Naloxone and needle exchanges. But these measures will not solve the problem on their own – greater social support is needed for heroin users, in areas including healthcare, housing and employment among others. Prescription heroin programmes must also increase nationally, rather than remaining isolated anomalies. We know that prescribing heroin to addicts works, and we know that criminalising them only increases harm not just to the user, but to society as a whole. With fentanyl’s inevitable arrival now upon us, the need for drastic change has never been clearer.

Sadly – but wholly predictably – the response so far has been anything but helpful. In Hull, where a surge in fentanyl-related heroin deaths earlier in the year first brought the impending crisis to national attention, police have launched ‘Operation Windsor.’ As with any clampdown, the increase in raids has simply led to the arrest and criminalisation of a number of low-level users. The producers and suppliers of the drug are left untouched by the law, in a depressingly perfect example of why current policy is unfit for purpose.

Deej Sullivan is a journalist and campaigner. He is a regular columnist for Volteface, writes on drug policy for politics.co.uk, London Real and many others, and is the Policy & Communications officer at LEAP UK. Tweets @sullivandeej