Go to a festival this summer, and drugs will never be far away. As the UK festival season gets underway, we asked Professor Fiona Measham to fill us in on this year’s festival drug trends, and what could be done to reduce harms resulting from drug use at festivals. In Part I, Fiona revealed how the Psychoactive Substances Act is already shaping drug use in the festival scene, now in Part II she sets out how technology and pragmatic thinking could combine to save lives at UK festivals.

Music festivals offer a brief escape from the stress or boredom of weekdays and weekends, a Shangri La of socialising, music, and for many, intoxication. Festivals may also contain unusually intense concentrations of recreational drug use, not just because of the nature of the activities – an extended weekend of partying night and day for many thousands of revellers, accompanied by eclectic entertainment, whilst knee-deep in falafel and mud – but also because of the increased opportunities to access drugs from random strangers, less feasible in everyday life.

In my research over the last six years at UK festivals, anything up to a third of festival goers have reported taking illegal drugs, depending on the type of festival, of course. Furthermore, a sizeable minority of these festival drug users are 30-, 40- and even 50-something adults who have otherwise hung up their party shoes for the rest of the year and retired from raving. This provides a unique opportunity for drug supply, from occasional and social supply through to seasoned ‘dealers’ with varying degrees of commitment to the responsible retail practises that we take for granted in the regulated market of alcohol, drugs and over-the-counter medicines. Illegal drugs can contain not only varying quantities of the intended contents but also adulterants and fillers. All of this produces a heady cocktail of opportunity, intoxication and risk, for festival drug users and dealers alike.

Currently almost all UK forensic testing occurs for evidential purposes, with seized drugs sent to laboratories by police after an arrest in order to identify their contents pending prosecution. In the UK this can take up to a month and can cost up to £100 per sample, a significant deterrent to testing in the cash-strapped criminal justice system. Alongside this, a handful of UK festivals operate ‘back of house’ on-site testing by police and associated civilians, again for evidential purposes and to monitor drug trends, although results may also be used to inform on-site services, depending on the resilience of multi-agency partnerships at that event. The overwhelming deficit in information about drugs circulating on site, contrasted with the intensity of use, left me as a drugs researcher asking how might we bridge this knowledge gap to the benefit of everyone at festivals, staff and customers alike?

[READ] Drugs, Dissociatives, and Displacement: The Festival Drug Report – Part I

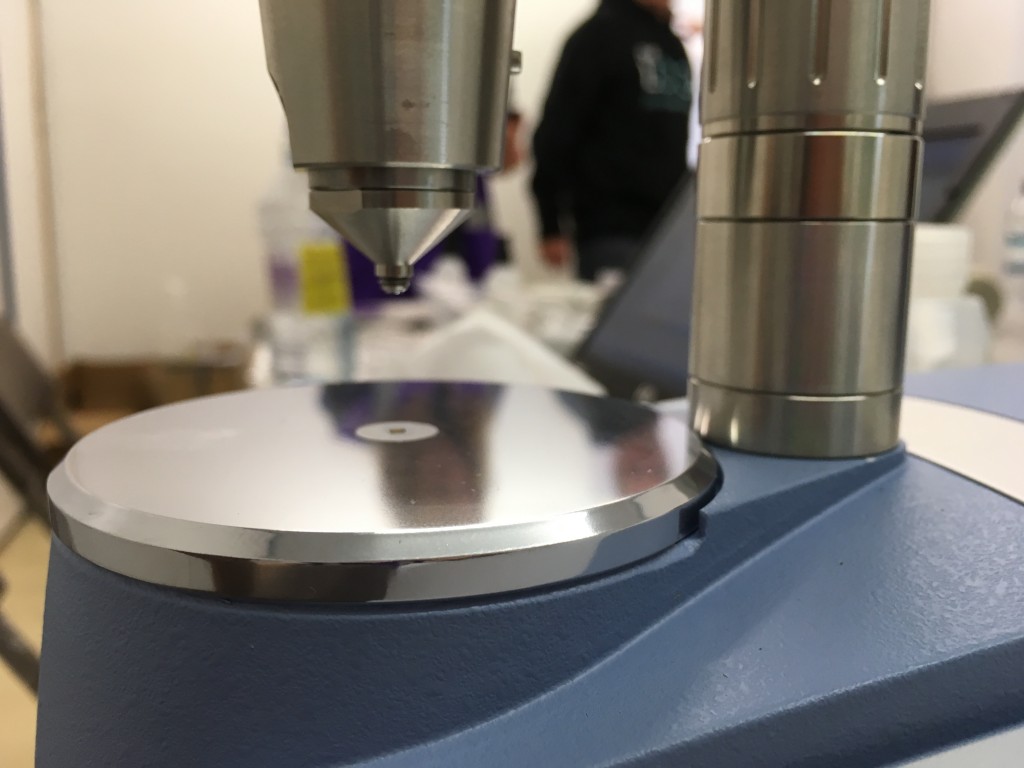

Three years ago, frustrated at the absence of harm reduction advice for recreational drug users, I co-founded The Loop to provide on site information and interventions. We also introduced what I call ‘halfway house’ testing as an additional limb of The Loop’s service delivery, facilitated by developments in testing technology. It is possible to carry a suitcase-sized laser to a festival that can identify any known drug to an impressive level of accuracy in 60 seconds. We introduced forensic testing at the Warehouse Project (still the only UK club to have on site testing for public safety) in 2013, and then at a number of festivals including Parklife, for which we won the UK Festival Award 2014 for Best Use of New Technology.

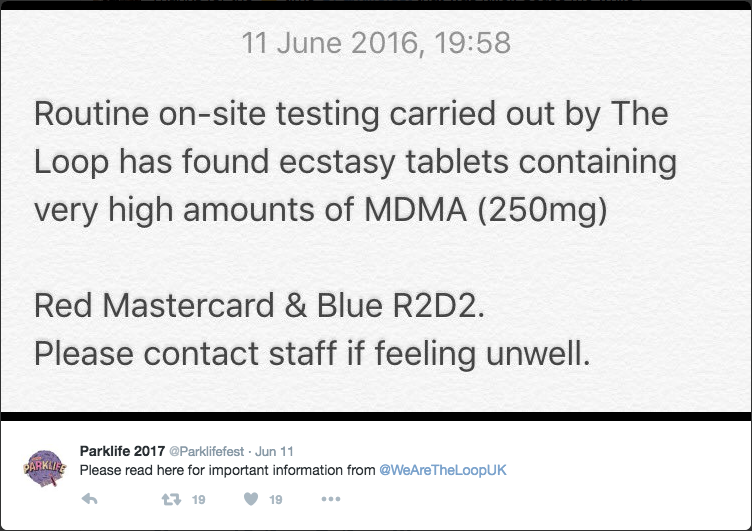

‘Halfway house’ testing is distinct from ‘back of house’ police operations because we test substances of concern obtained from any on site services, not just seizures, confiscations or amnesty bin donations. This includes medical, welfare and security incidents, with results circulated to all on-site services. This also allows The Loop to monitor drug trends, identify risky substances in circulation and put out real-time alerts to inform festival goers and the wider public about drugs in circulation. For example, at a Manchester festival this summer The Loop tested ecstasy pills varying in strength from 20-250mg of MDMA on just one day at just one festival. The risks of festival drug use can also extend beyond the festival and irresponsible retail practices on site. For example, high strength ecstasy pills recently led to the hospitalisation of three young girls who raided their uncle’s festival stash.

Of course there is a key piece of the jigsaw missing: drug users themselves. By including this group we can link rapid analysis of a sample with individual user accounts of the drug and its effects. Some European countries have added drug users to the mix and taken testing another step forward with ‘front of house’ testing or ‘drug checking’. There are charity initiatives such as Safer Party in Austria and public health initiatives such as the Luxembourg National Drug Action Plan 2015-19.

So what are the additional benefits of adding users to the mix? In Switzerland there have been no ‘party drug’ deaths in the last six years, which the authorities believe is due to drug checking. Indeed in Zurich, drug related problems are considerably lower than elsewhere in Switzerland, which has less drug checking, whereas the reverse might be expected given that Zurich has the most clubs, parties and consumption of ‘party drugs’.

Alongside all the benefits of ‘halfway house’ testing (informing emergency services, tracking trends and so forth) users can receive information directly about substances of concern that they or their friends have taken or may be considering taking. This provides a vital opportunity to link what individual users think they have bought with what they have actually bought, and thereby can lead to more productive harm reduction messaging, perceived by users to be more trustworthy because it is grounded in the realities of drug markets.

On-site testing can identify misselling by dealers, such as methylone and table salt for MDMA; methoxetamine for ketamine; and ketamine for cocaine (all of which The Loop has tested), which increase the profit margins and reduce the risks for dealers along the supply chain, but add to the risks for users from unexpected consumption of these alternatives.

Of course, front line suppliers may have little idea themselves of what is actually in the drugs that they sell, they rarely have access to such technology. Yet many of the regular users that I have interviewed choose to buy their drugs off someone they characterise as a trusted, known local dealer rather than ‘chancing it’ with chancers on site – an understandable harm reduction strategy when operating in an illegal market. This is counterbalanced by having to run the gauntlet of security upon entry, risk getting their festival party pack confiscated and themselves arrested, and having to buy replacement drugs from randoms.

[READ] Man’s Best Friend – Festivals, Sniffer Dogs, and Your Rights by Release

‘Front of house’ testing is a pragmatic response to the current situation of illegal and unregulated drugs sold by suppliers who themselves may be unaware of the contents. The obvious and easy criticism of testing is that it is a quality assurance measure for the illegal drug trade, as well as potentially increasing drug use and associated drug-related harm.

- Firstly, it can reduce on-site dealing by identifying and warning about misselling on site, as my own testing does each year.

- Secondly, evidence from Europe suggests that in fact ‘drug checking’ highlights the variability of illegal drugs and reduces experimentation by new users. When provided with their test results, a Canadian project found that half of festival goers chose to dispose of their drugs. For those who do continue with their planned consumption, they may change the amount or circumstances of consumption.

- Thirdly, while drug checking is unlikely to lead to an overall reduction in prevalence of drug use, it can and does lead to a reduction in drug-related harm, including targeted and more efficient use of emergency services on and off site. Dr. Tibor Brunt, of the University of Amsterdam, suggests that the Dutch Information Monitoring System (DIMS) has not increased drug use but instead has resulted in decreased mortality rates, leading him to conclude that accurate and timely public health warnings can be successful. An example of this would be the emergence of red Superman pills containing PMMA that resulted in 4 deaths over Christmas 2015 in the UK but none in the Netherlands.

Festival forensic testing won’t stop drug use but it will reduce harm and save lives. And the greater the input from all on-site stakeholders, including users, the more effective on-site testing will be.

It’s #TimeToTest

Fiona Measham is Professor of Criminology at Durham University, Co-founder and Director of The Loop drug, alcohol and sexual health service, and Member of the Advisory Council on the Misuse of Drugs. Tweets @FMeasham

You can support The Loop’s #CrushDabWait campaign by buying and wearing a #CrushDabWait T-shirt or hoodie from the Release shop here.

The Loop is a not-for-profit community interest company established in 2013 by Fiona Measham and Wilf Gregory. It provides free, confidential and non judgemental advice and information on drugs, alcohol and sexual health at nightclubs, festivals and other leisure events in the UK and mainland Europe, as well as providing the only UK civilian forensic testing service focused on public safety at such events.