Last month marked the 1-year anniversary since the re-launch of AlphaBay Market, a darknet marketplace which shut down in 2017 in a highly publicised international sting which led to the mysterious death of its founder, Alexandre Cazes, in a Thai prison cell.

With a successful first year back in business pioneering new innovations in operational security, its original co-founder DeSnake released a celebratory message in which they launched the “AlphaBay Harm Reduction Program Professional Drug Checkers” – a service which pays selected users to purchase products from vendors to conduct two tests that determine strength and purity. The results are then added to the vendor’s profile and strict penalties are in place for vendors with adulterated or mislabelled drugs. This development is a first-of-its-kind, and just the latest example of the innovative harm reduction initiatives pioneered by darknet marketplaces.

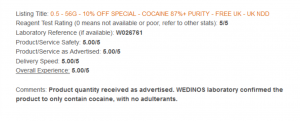

Figure 1: Harm Reduction Review on AlphaBay

The last decade has seen the evolution of the darknet market ecosystem, comprising of Amazon-style marketplaces for drugs of all kinds and the forums and messaging boards which orbit them. This has cultivated an online community of vendors and users who have built a mechanics of harm reduction into the very architecture of this “brave new world”.

This has manifested in customer reviews, drug testing, mass adulterant warnings, community support, user-based guides, and even darknet forum ‘Ask Me Anything’ sessions with harm reductionists such as Dominic Milton Trott, author of The Drug Users Bible. Centred around harm reduction and risk mitigation, Trott’s book follows the belief that “The first casualty of war is truth, and the war on drugs is no different”.

By 2017, AlphaBay, which had replaced Silk Road as the largest, most sophisticated marketplace, was also leading the way in harm reduction. Alongside its customer review model, users were finding ways of reducing harm in the mist of a looming opioid crisis – the leading cause of accidental death in the US at the time.

One vendor called Grand Wizard’s Lair was offering “recovery packs” comprising of three different medications which ease the painful (sometimes life-threatening) side-effects of opiate withdrawal as well as working to eliminate cravings. The product reviews speak for themselves:

“Got mine 3 days after order! I had 12 years sober, but a bitter divorce and a case of the “fuck-its” has had me strung out for the past year at about 5g a day. 🙁 Today is the day I start kicking and get back to my life again, wish me luck and thank you so much for these!”

“you are the best!”

“10/10, and the low price is well worth the amount of pain you will avoid! every opiate user should have a little stock of these pills just in case. I ordered them thinking I might never use them, but I was praising”

In this case, these users were benefitting immeasurably from access to a transparent, quasi-legal market, allowing them to withdraw and detox with dignity – an experience otherwise known for its nausea, insomnia, nightmares, rapid changes in body temperature, and uncontrollable shaking. “Long Live the Revolution” the vendor’s bio read, “They can jail a man but they can’t jail a dream”.

After three years of business, reaching 400,000 users, AlphaBay suddenly went offline. At the time, many suspected an exit scam. In a panic, displaced users of AlphaBay migrated to the next-best market, Hansa – oblivious that it was being run by the Dutch police, who, in a carefully orchestrated manner, syphoned the details of the thousands of migrating users (or, refugees, as they were called).

Two weeks later, both AlphaBay and Hansa displayed an official seizure notice. United States attorney general, Jeff Sessions described it as “one of the most important criminal investigations of this entire year”, in an internationally coordinated mission called ‘Operation Bayonet’.

Figure 2: AplhaBay Seizure Notice

In this case, law enforcement won the battle, but not the war. While the legacy of AlphaBay had seemingly died along with its founder, the darknet market ecosystem carried on unscathed, with other marketplaces ascending to prominence. However, four years later in August 2021, AlphaBay rose from the ashes, led by its original co-founder, DeSnake (verified by his PGP key, a kind of encrypted personal signature). In a public message he wrote:

“AlphaBay has always been a principle-driven, vision-oriented and community-centered marketplace. The administration is almost the same as in the 2014-2017 period which means you will find again AlphaBay runs with mature management, unparalleled security, 24/7 professional & well-trained Staff and of course unique vision for the future not only for itself but for the darknet market scene too.”

In another message, DeSnake paid tribute to his predecessor Alexandre Cazes, known as alpha02, who he believes was “Epstein’d” or “Mcaffee’d”.

“Another reason of vital importance of why AlphaBay is returning is how everything ended with alpha02 (…) That complete disregard for human life by Law Enforcement made me make the decision that alpha02 deserves to be honoured and no one was ready or going to do it so fuck it here I am doing this. (…) I want to dedicate this to alpha02 first and foremost we promised each other to go to the bitter end, here I am keeping my end of the deal.”

A year later, having returned to their spot of market leader, DeSnake launched the “AlphaBay Harm Reduction Program Professional Drug Checkers” in a message to users last month. This market-funded service pays trusted buyers to purchase products from vendors and test them twice – once with a Reagent home-testing kit, and secondly by sending a sample to a drug checking laboratory such as WEDINOS in Wales, or Energy Control in Spain to verify the contents and purity.

This is paired with the rule that all products must be correctly labelled, incurring the immediate ban of vendors for whom fentanyl is found to be in any product without prior labelling. The same products are then purchased and tested later at random intervals to ensure consistency.

Make no mistake – this is a lifesaving service. In my research on darknet forums during the height of the opioid crisis, many people would ask for harm reduction advice, having been forced into the shadows by our government’s criminal justice approach. Occasionally, a prominent user would suddenly stop posting and drops off the radar, the assumption being that they overdosed and never logged back in.

In comparison to the alternative of purchasing from a street dealer with no knowledge of the strength or purity of the product, the darknet marketplaces resemble a utopia. However, for all its successes, this is merely a drop in the ocean of the harm reduction which could be achieved under legal regulation.

The success of darknet harm reduction is a testament to the failings of the drug war. While these innovations have already legalised drugs by proxy for its users, a move towards legal regulation would radically safeguard vulnerable people, make our streets safer, and migrate the profits out of the hands of organised crime groups and into public infrastructure.

More importantly, the need for harm reduction would itself reduce under a legal regulation framework in which production and supply is standardised. Conversely, the customer reviews and adulterant warnings we see today merely serve to mop up the blood spilled by prohibition.

This piece was written by George Smith(BA SOAS, MA Bristol). Tweets:@GESmithResearch. George is an anthropologist, his ethnographic research among British “new age” travellers was published in the SOAS Research Journal, and his research on darknet marketplaces was presented at the British Sociological Association’s annual conference. His latest project ‘Whose Republic?’ explores the creative expression of spatial politics in a gentrified area of Bristol, which will be presented at the Royal Anthropological Institute’s annual conference next year.