The House of Commons debate last Monday was a fantastic display of support and solidarity for families, campaigners and advocates alike, all hoping to expand access to medical cannabis that remains almost entirely inaccessible on the NHS.

Speakers from across the House offered emotional and impassioned pleas for intervention by Under Secretary for Health Jo Churchill, calling for: better education and direction for prescribing medical professionals in the NHS; the consideration of an observational study to alleviate the need for children suffering with refractory epilepsy to come off their medication as part of a placebo group; and temporary financial support for the seventeen families currently eligible.

Interestingly, a sizable number of the speakers discussed the reputation of the term ‘medical cannabis’ and its language as a focal point of their time. Many MPs claimed the besmirched reputation of the word ‘cannabis’ actively impedes upon access, where doctors may be wary to prescribe due to its connotations.

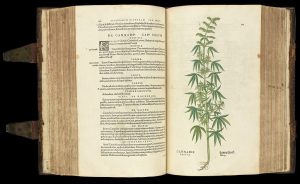

It would not be the first time advocates have concertedly shifted the terminology of cannabis. Burdened by its racial connotations, the Mexican term ‘marijuana’ was co-opted by prohibitionists in 1930’s America in order to manufacture an impression of the drug as ‘un-American’, and justify the over-policing of non-white groups’ possession and consumption of cannabis. While this blighted history is well-known in advocacy circles, the origins of the dissemination of this term remains hidden from the general public.

The MPs’ speeches reflect the tendency of a fragmented movement to ‘break off’ from its predecessors burdened by history, as they advocated for the rehabilitation the reputation of medical cannabis. In practical terms, this might look like replacing ‘cannabis’ with ‘cannabinoid’, ‘hemp’, or referring to the specific compounds within cannabis-based medicines.

This article will first look at the benefits of a rehabilitated image for cannabis, starting with its name. It will then turn its attention to the arguments against embracing new terminology for cannabis-based medicines both for cannabis users and people who use other drugs.

THE CASE FOR

Insurmountable fear & a clean slate.

“In this House, we should not be using the word “cannabis”, because it strikes that fear into the hearts of many, many people across the UK.”

Tonia Antoniazzi, Labour MP for Gower.

“I think this problem might be to do with the terrible word “cannabis” that we use in this country. This is not anything to do with cannabis, really; I wish we could invent another name for it and just say “oil with TCHs in it”, because that would eradicate much of the fear that there is at present—and it is not just fear, it is dangerous to the argument.”

Sir Mike Penning, Conservative MP for Hemel Hempstead.

For as long as we have seen representations of cannabis in the media and politics, it has been intrinsically connected with fear. The early 20th century saw the immediate categorisation of the drug by politicians, doctors and police as one with the capacity to morally corrupt the British people.

This assumption was directly informed by racist and imperialist ideologies that connected the use of cannabis among immigrants and non-white residents with danger to upstanding communities. A moral panic was manufactured out of fear of a drug that had predominantly existed in countries which had been colonised by Britain. Cannabis and hashish was a perceived problem by the colonizers; thus, authorities sought to control it.

This panic has persisted for over one hundred years, its malleable state allowing ‘cannabis’ to be a vehicle for suppressing the anti-war ‘hippy’ movement and racial equality movements in the US through fear-mongering.

MPs in the Commons debate have aptly understood the crux of all issues pertaining to drug policy reform: decisions that engage first with fear, and then with reason. Jonathan Haidt’s’ The Righteous Mind’ uses the analogy of a rational Rider atop an intuitive Elephant, where the former is in control until the Elephant’s overpowered, primal instincts are alerted. If we eliminate the initial alarm- the instinctual and fearful aversion to ‘cannabis’- we can more readily appeal to our target (in this instance, medical practitioners).

While the process of overcoming this initial and intuitive fear with heroin, cocaine, or recreational cannabis use may be a longer process, medical cannabis is not necessarily positioned in the same way. Already distinct due to the reforms in 2018 which created a legal pathway for access, medical cannabis is an unnecessary casualty in the War on Drugs and for this reason needs to be, above all else, uncontroversial.

By separating medical cannabis from the term ‘cannabis’ and embracing an alternative, we might start to quell the instincts that encourage the reluctance to prescribe the life-saving medicines. It is an easier win than doing so for all drugs, so should we not take our victories and prioritise the wellbeing of suffering patients?

While not explicitly mentioned in the debate, it is important to recognise that before 2018 much of the understanding around cannabis in primary care was tied to its alleged link with psychosis. If a GP was approached by a patient who was self medicating with cannabis for conditions such as anxiety and depression, their apprehension to support this would be understandable. Since its legalisation, however, revelations of the ability of cannabis-based medicine to effectively manage symptoms in a variety of mental health conditions have emerged.

It could take years to re-inform and shift medical opinions on cannabis-based medicines, especially where patients are either children, or have a mental health condition. But if a new term free from the drug’s loaded history and preconceived understandings was popularised, it could help accelerate this necessary shift. Ultimately, increasing patient access has the potential to drastically improve patient outcomes and reduce harms, the cornerstone of medical intervention and care.

A line in the sand.

“[…] the crucial thing about when the law was changed was that it was about the prescribed medical use of cannabis oil by a specialist consultant, not a GP. It was not about a spliff behind the bike sheds or anything like that; it was prescribed medical use that saved children’s lives.”

Sir Mike Penning, Conservative MP for Hemel Hempstead.

“Does she [Christine Jardine MP] share my frustration—I am sure she does—that the debate around medicinal cannabis is often confused with people who just want to smoke dope and drop out? “

Adam Afriyie, Conservative MP for Windsor.

“If we continue to talk about medicinal “cannabis”, stigma will continue to attach to the part that gives a hallucinogenic effect. That is the part that everyone will focus on unless we start to change the direction, the language and the naming, which is why the medical profession is blackballing it on every occasion.”

Paul Girvan, DUP MP for South Antrim.

Another crucial argument in favour of changing the way we talk about medical cannabis is in pursuit of the separation between medical and recreational cannabis use. It is true that the reputation of medical cannabis users have been conflated with those of recreational..

Since the inception of the Misuse of Drugs Act, cannabis has been presented as equally dangerous as heroin and cocaine for both the individual and society. Cannabis use and users attracted multitudes of misinformation and inflammatory headlines. The criminalisation, and ultimately stigmatisation, of those who use cannabis continues to underpin medical opinions and understanding of the harms and risks associated with prescribing cannabis as a medical treatment.

The risks of being associated with recreational cannabis may limit a doctor’s confidence in advising, and supporting patients who are trying to obtain cannabis medicine, and prevents them from accepting cannabis-based medicines as legitimate treatment pathways. .

If the Rt. Hon. Paul Girvan is right, and the continued association of medical cannabis use with its recreational use is the primary inhibitor of reform, we must seek to alleviate this associated stigma. A holistic rehabilitation of the image of cannabis is possible, but it could take decades to do so. People are dying now, and children are suffering,

Ronnie Cowan MP suggested, “let us call it ‘medical hemp’”.

But is it that simple?

THE CASE AGAINST

“[…] the core of the problem [is] the reputational issues that we are dealing with. We owe it to our constituents to do just a little better. We owe it to them to try to understand the evidence and create institutions that will advise our Government based on the evidence. We have a duty not to be stampeded by the popular press in a particular direction about the particular meanings of words, but we have done so for 50 years in regard to cannabis”

Crispin Blunt, Conservative MP for Reigate.

Realistic assessments of use.

In spite of the Hon. MPs’ claims, a neat distinction between recreational and medical use of cannabis (nor other drugs) simply does not exist.

Neurosight and Students for Sensible Drug Policy UK’s ‘Student Drug Behaviour and Mental Health during COVID-19’ survey contains compelling evidence to support this stance. Among students who had taken illicit drugs in the 2020-2021 academic year, as many as 36% reported that they had never or rarely used drugs with socialisation as their primary motivation.

For those students who used drugs daily, motivations related to mental health including dealing with anxiety, relieving depressive symptoms and escaping reality were uniformly cited most.

These motivations can be considered both recreational and medical, and are the reality for many cannabis users.

The media and politicians’ tendency to separate cannabis users into either critically ill or irresponsible pleasure-seekers is therefore inappropriate, failing to take into account the myriad nuances between the two classifications.

The reality is that most cannabis use is more complex than the distinction between chronic illness and not, unable to aptly be pigeonholed into neither recreational nor medical. Therefore, in drawing a line in the sand we are ignoring the needs of the vast majority of cannabis users, who are still at risk of criminalisation, and other harms associated with the prohibition of cannabis.

Working with fear, not against it

“All of us have a duty to […] be able to disaggregate all the issues and negative connotations associated with the use of cannabis”

“We refuse to listen to the evidence because it will be politically inconvenient and subject to misrepresentation in the media. We owe our constituents way more than that”

Crispin Blunt, Conservative MP for Reigate.

In the Commons debate, the implication was clear; The policy deadlock and reform for access to medical cannabis access should be delineated from the wider drug policy reform movement. The fear instilled by the word ‘cannabis’ was presented as insurmountable, and as such in order to expand access to medical cannabis, we must abandon the term in and of itself.

While doing so may be immediately advantageous for medical cannabis reform, the consequences for the wider drug policy reform movement would be devastating.

Advocates, activists and reformers have been pursuing the holistic dismantling of the War on Drugs since its creation. The movement has made incredible triumphs that encouraged research into cannabis-based medicines, and successfully lobbied for its legalisation in 2018.

This was done so in the interest of saving lives and reducing harm above all else, a mission shared by medical cannabis campaigners.

To draw a line in the sand between medical cannabis and other drugs, including recreational cannabis, would be disastrous to the advocacy efforts of drug policy reformers.

This symbolic betrayal has real-world consequences. The ONS recently released devastating and unprecedented drug-related death statistics for England, Wales and Scotland for 2020, showing the real-world catastrophic consequences of the dehumanising drug policy of the UK government.

Anything short of a holistic dismantling of the War on Drugs, achieved through humanising policy that does not distinguish between users of caffeine, ketamine and heroin, is insufficient. If the concern of MPs is of saving lives, specifically those most vulnerable, we cannot afford moral high-grounds in our pursuit of change.

Should we abandon the term ‘medical cannabis’ to encourage more comfort and trust in prescribing the life-saving treatments among GPs?

Should we instead seek to change minds, benefitting wider drug policy reform?

We want to hear your opinion! Have your say on Twitter (@Voltefacehub), Facebook, or Instagram (@Voltefacehub).

This piece was written by Content Officer Issy Ross (tweets @isabellakross) and Operations Officer Ella Walsh (tweets @snoop_ella).

Lead image credit: https://www.pxfuel.com/en/free-photo-xzpnr