Does anyone? Drug prohibition is getting in the way of psychoactive drugs research

How can you answer a question if the answer doesn’t exist? Let’s examine the case of *Fiona. She had previously experienced depression and thanks to therapy and medication was now symptom-free for over a year. However, after taking MDMA on a night out, she felt that her depressive symptoms had come back.

She went to her psychiatrist for advice, but they were largely unable to answer. Why did that happen? Well, according to our research, one of the issues is that illegal psychoactive drugs like MDMA are being less researched than their legal counterparts like alcohol. This has created a dearth of peer-reviewed scientific information on these drugs, and drug prohibition can certainly take a fair share of the blame.

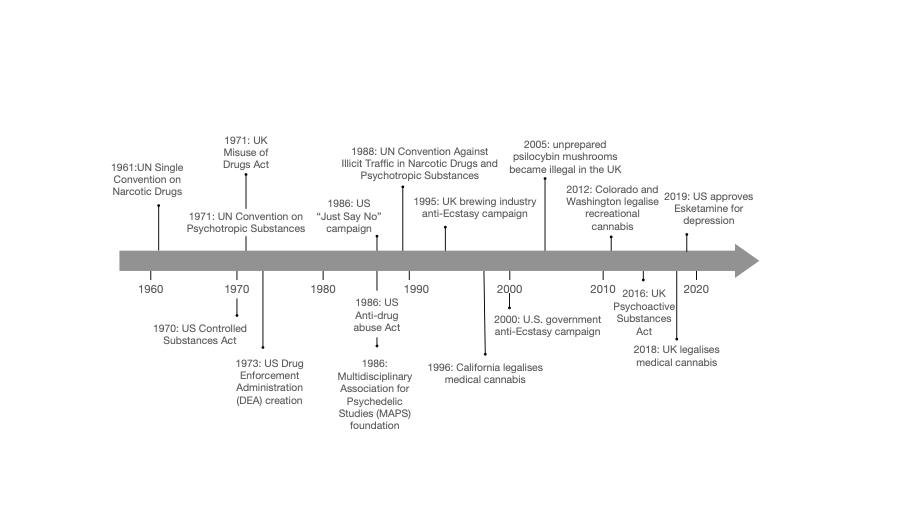

With the UK Misuse of Drugs Act 1971 “celebrating” its 50th anniversary last year, the war on drugs has had a profound impact on the world. Starting with the UN Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs in 1961, restrictions were placed on the trading and consumption of certain psychoactive drugs.

Using the perceived potential for harm/addiction and their accepted medical uses, they were placed into categories: schedules in the USA and classes here in the UK. Drugs like MDMA are heavily restricted, whereas alcohol can be legally acquired in licensed establishments. The idea behind these laws is to reduce trade and consumption of these drugs, with the intent of protecting citizens of the world, but policymaking really isn’t that simple.

The classification of individual psychoactive drugs is an ongoing and raging debate. A landmark paper by Nutt el al. has challenged how potential for harm is assessed, crucially integrating the component of social harm, shooting alcohol to the top spot, above heroin.

For the other component of psychoactive drug classification – their accepted medical uses – to evolve, research must be carried out. However, as we outline in our paper, there are several challenges that researchers face when researching illegal psychoactive drugs, such as costly and difficult to obtain licences which last for very short periods of time. This has led us to believe that an unintended consequence of these legislative frameworks has been the limitation of research on illegal psychoactive drugs.

How am I so sure? For nearly seven years now, I’ve been involved with Drugs and Me. Our core mission is to help people make more informed decisions about using psychoactive drugs, prompting us to notice first-hand the lack of reliable information. This piqued the interest of Ivan, our co-founder and director. He was surprised to find that there was little in terms of formal research into the impact of drug prohibition on research into psychoactive drugs. Ever the scientist, he enlisted Julia and I to try to make sense of the question together.

First, we chose 15 psychoactive drugs that would provide a good representation of the different drug classes and legal statuses. Then we went on to Web of Science, one of the biggest databases of scientific papers in the world, and looked at nearly a million papers published since 1960 about these 15 drugs. Finally, we plotted the data and analysed it against a timeline of international and national events in drug policy to test our hypotheses, which you can see below.

This last part was crucial to us because the whole point of this research was to see if drug policy and the legal status of a drug affects how much research attention it receives. Just demonstrating that there is a skew wouldn’t say that much; so much alcohol is consumed worldwide that it is normal that a significant amount of research is oriented towards it. But if there is a clear pattern consistent with key policy changes as in the timeline we constructed for our paper, then that’s a pretty good argument.

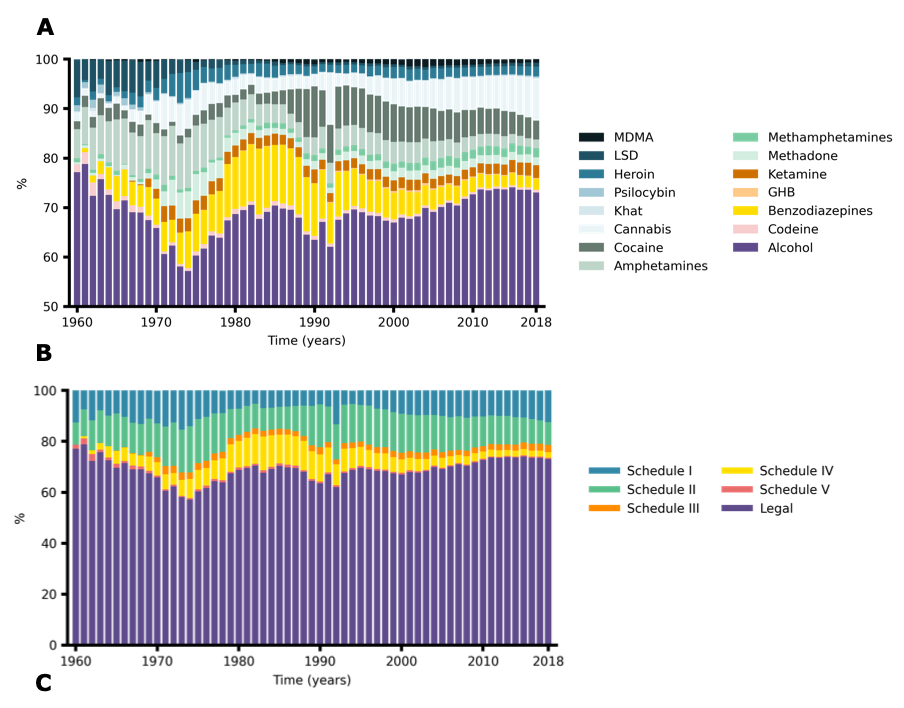

What did we find? Well, our findings support our original hypothesis: the legal status of a drug seems to have an impact on the amount of research that is dedicated to it. Let’s look at some examples based off figure 5 of our paper, which you can see below. In this figure, we looked at the total yearly publications for all 15 drugs, plotting the amount of research dedicated to them as percentages. Cannabis is an interesting drug to examine as its legal status has evolved a lot over the years, especially in North America.

When we separated each of the 15 drugs on the plot (fig. 5A), the amount of research starts to grow quite visibly from 1996 onwards, which coincides neatly with the legalisation of medical cannabis in California in the USA. And there still clearly is a research gap since the National Institute for Health (NIH) in the USA has just put out a “notice of special interest” calling for more research on cannabinoids and cancer. When we plotted the drugs by legal status (fig. 5B), we found a massive skew towards legal drugs, with consistently 60-80% of papers dedicated to investigating them across the entire studied time period.

This is all further supported by our analysis of the growth patterns of research carried out on each individual drug, whereby research on legal drugs typically follows a classic pattern of exponential growth whereas research on illegal drugs has stuttered and atypical growth, at times even negative.

So why does this even matter? Let’s revisit *Fiona’s story, because it turns out that there is in fact an answer. Recent clinical trials on the effectiveness of MDMA for treating various mental health issues such as depression and PTSD have yielded insights into the drug itself. Sessa et al. have reported that “Blue Mondays”, a period of low mood often reported after taking MDMA, don’t happen when the drug is given in a clinical setting, which indicates that the effect is probably not due to the drug itself, more likely arising from adulterants and the general punishment a big “sesh” puts on one’s body and mind. Let’s be crystal clear here, there are a number of reasons that the psychiatrist was unable to answer Fiona’s question.

For example, a severe lack of teaching about psychoactive/recreational drugs in medical school, which leaves medical students feeling unprepared to deal with issues related to psychoactive drugs. But it is fairly clear that drug prohibition is having a significant effect on the amount of research that is being carried out on illegal psychoactive drugs and without that basic knowledge, we can’t do anything. Let’s be emboldened by the success story of cannabis and free up research on psychoactive drugs; we will all benefit.

Drugs and Me was created because we believe that knowledge is crucial in empowering individuals to make smarter and healthier choices when using drugs. If you want to support our non-profit mission and receive cool benefits, head over to our Patreon. You can also follow us on Instagram.

*names changed for the purposes of anonymity

Read the paper in the Journal of Drug Issues. Connect with Arthur on Twitter or LinkedIn.