During his presentation of the 2017 budget last week, Chancellor Philip Hammond mentioned a £28 million financial aid allocated to the Housing First programme to tackle rough sleeping in the United Kingdom. This measure confirms the Government’s pledge to halve rough sleeping by 2022 and eradicate it by 2027.

The success of the Housing First programme (initially developed by psychiatrist Sam Tsemberis in the USA), lies in its core innovation: moving rough sleepers directly from the street to individual and permanent housing.

At present, the traditional support scheme for rough sleepers involves what is known as the ‘staircase approach’ to housing. This results in a person moving from one place to another multiple times as they progress through the system.

Jo Prestridge, Housing First England Project Manager, reported that “people get stuck in that staircase”. As people go up the staircase, each stage has less support, and people are faced with “goals that are unattainable, they needed to be perfect rather than ordinary to have their own housing”.

The Housing First programme provides far more support than standard models of resettlement. Social workers allocated to Housing First will have caseloads of 5 to 7 people, a far more manageable number than 40-50 which is often the seen on traditional schemes of housing support.

A smaller caseload allows Housing First to address the multiple and complex needs of each rough sleeper, providing thorough, dedicated care on the complex issues they present with. For some this might be simply providing a birth certificate so that the individual can gain faster access to housing. In other cases, which are sadly frequent and commonplace, the support is focused on serious physical and mental health needs of the individual.

Regarding drug dependency, Housing First has a harm reduction approach. The focus here is to reduce the overall harm caused by drugs and alcohol rather than immediately stopping use. For many the end goal remains abstinence, and the programme does encourage such an outcome, but this is crucially not a prerequisite to being housed. Many existing housing schemes do have this requirement which becomes for many an exceptionally difficult barrier to overcome whilst they remain living on the streets.

According to the Housing First principles, the success of the initiative cannot be achieved if the rough sleepers do not keep as much independence as possible. This involves giving the choice of accessing treatment rather than such a decision being enforced, a basic human right according to Housing First.

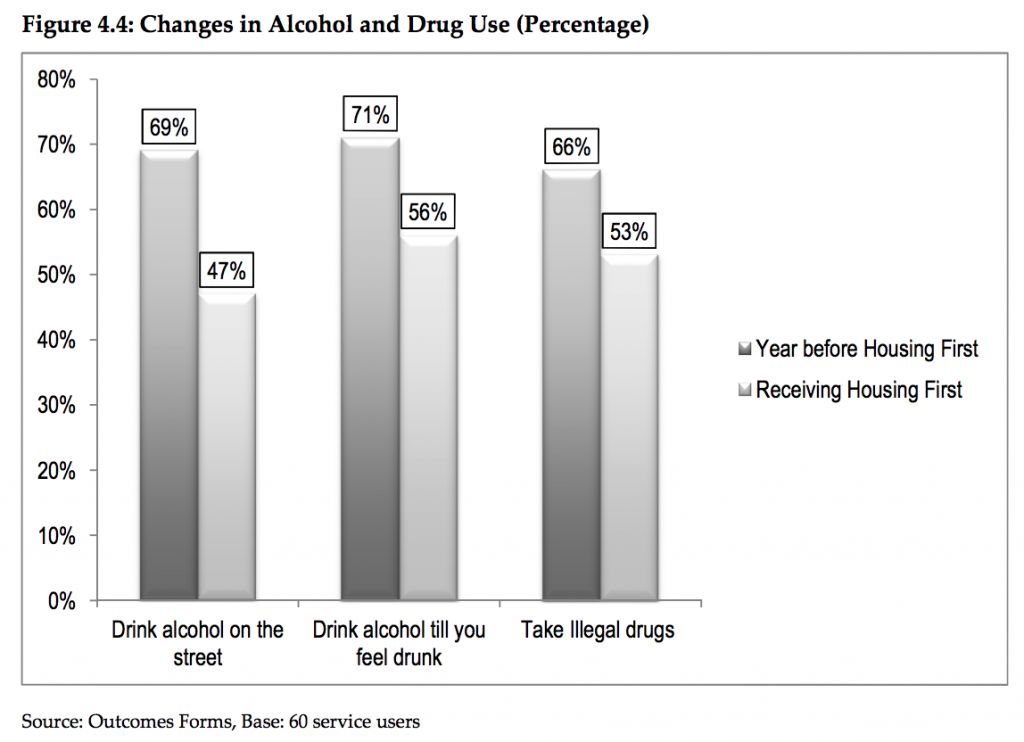

As stated by the Housing First project lead in Glasgow, “with regards to the harm reduction approach, service users emphasised that this enabled them to be “honest” about their addiction and their use of drug and alcohol and that they don’t have to “lie” when they experience a relapse to avoid losing their flat.” The graph below highlights the success of this approach.

Among those who entered treatment, significant progress have been monitored. Research from the University of York investigating the effectiveness of Housing First in England showed that:

“There was some evidence of reductions in drug and alcohol use. Among the group of 60 service users completing outcomes forms, 71% reported they would ‘drink until they felt drunk’ a year prior to using Housing First, falling to 56% when asked about current behaviour. When asked about illegal drug use, 66% of the same group reported drug use a year prior to using Housing First, falling to 53% when asked about current behaviour.”

Liverpool and Manchester, two of the three cities receiving the substantial government aid to develop Housing First projects, are particularly impacted by rough sleeping and public drug use.

In Liverpool, drug litter (e.g. discarded needles and syringes) has been reported by my colleague Liz McCulloch to have increased by 611% between 2012/13 and 2016/17. Manchester is one of the UK cities with the highest rates of rough sleepers in the UK, with an average of 78 people sleeping in its streets every night, according to Homeless Link, and known for having a problem with public drug use.

The £28 million Government aid given to these areas, along with West Midlands, will boost the success of Housing First in order to get rough sleepers out of the streets and reduce their drug dependency thanks to their effective harm reduction approach.

“I think housing first offers multiple services to the complex needs of rough sleepers and gives them an opportunity to find a home and address their needs. There are a number of Housing First projects across England that are being developed, and this announcement is really welcomed in terms of opportunities it provides to people across these cities.” – Jo Prestridge

Pierre-Yves Galléty is Communications Officer at Volteface. Tweets @PYGallety