With the ongoing climate crisis, there has never been a more urgent need to question our relationship to material production; currently the construction industry contributes to 40 percent of global carbon emissions. This figure is related not only to the operating energy of the building, the heating and maintenance, but also the materials used for construction and demolition.

The materials most widely used in the construction industry are the direct result of extraction, relating to commodifying the ground and its ungrounding. The most widely used material within this is concrete; quick, cheap, and easy to build with, its use has expanded dramatically since the postwar period. A mixture of sand, aggregate and cement, it has become our way of controlling, supplanting nature, building not with the resources available but instead with the easiest option for expanding into the city.

This is crude oil architecture at its peak, and the results have been disastrous for the environment; concrete is said to be responsible for 4-8% of the world’s CO2. This dependence on finite materials creates resource scarcity, fuelled by a western desire which fixates on the use of new, virgin materials. The impact of this construction caters to an ever-expanding city, a place where pollution and toxicity excel while biodiversity and human health are on the steady decline. This poses a fundamental question: how can you continue to create buildings within urban areas, without relying heavily on extraction?

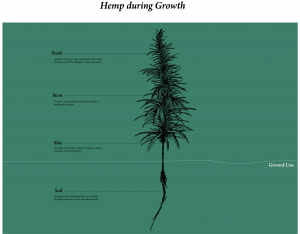

Enter Hemp. As a plant, it is functional, fibrous, and fertile; it has a history of use, both as a construction material and as a cultivated product. Binding together the Shiv, the stem of the crop and normally a waste product, you can create Hempcrete, a wet, biscuit-like material which can be used as a great construction material. Hemp is mixed with lime, and becomes a versatile material, suitable for a range of uses within a building. Hempcrete has warm, insulatory properties; the development of which could provide a great substitute for our dependence on Concrete.

Hempcrete also has thermal mass properties, like concrete, which means the material can work with the sun, absorbing heat during the day to then emit slowly throughout the winter. This has always been used as a justification for using concrete, as despite its extractive and harmful properties, current sustainable buildings still advocate for its use. It seems a backwards step, to extract a material and then promote it as climate friendly and this reliance on quick and easy concrete construction accelerates the carbon footprint of each building.

Sustainable Architecture is currently geared towards reducing carbon within the building’s use, not within its construction; this has led to buildings such as the Bloomberg headquarters in London, which although is listed as the most sustainable office building, relies on lavish materials imported from extracted means around the world. The properties of Hemp could seek to subvert this, ushering in a new regenerative age, in which buildings can become attune to the landscape they are grown from.

Unfortunately, Hemp as a material has been subjected to the process of discrimination; both the War on Drugs and the propaganda from plastic companies within the late 1960s created a criminalisation of the separation plant, attaching a stigma which has been hard to shake off. This has also prevented further research into the many uses of the crop, limiting both its production and cultivation. Despite the UK having a long heritage of building with Hemp, it is only now, with the looming threat of Climate Change, that Hemp as a building material is finally beginning to flourish in use.

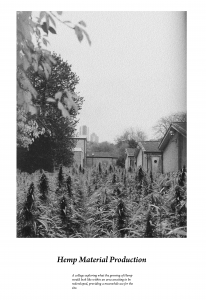

Flat House by Practice Architecture and Material Cultures sought to subvert the traditional uses of Hemp building through utilising emerging technologies. Their house was made in Margent Farm, Cambridgeshire, and grown from Hemp crops harvested in the surrounding fields. It featured on site construction and was easily assembled in a matter of days. Since completion, it can be viewed as a case study in how building with Hempcrete can not only result in a more environmentally friendly house, but also a warmer, more open, and natural way of living. The combination of off-site construction and home-grown materials argues that, despite having a seasonal harvest, Hemp as a material could easily slot into the design and build projects happening around UK cities.

Current legislations put in place restrict the production of Hemp; though the Shiv, fundamentally seen as a waste product, can easily be harvested, and used within the construction industry, the UK government restricts the cultivation of plant without an appropriate licence. This creates a boundary to those interested in growing Hemp, making it less appealing for farmers who, instead of harvesting and selling the product, must burn the most economically viable part of the harvest. This also poses challenges within a setting for growing individual plants, as it makes it not only economically unviable (a license just to grow the crop costs upwards of £500), but also subject to a huge amount of faff. Instead of promoting a landscape-led redesign of our current material system, the UK is falling at the first hurdle, restricting the capabilities of carbon neutral construction.

This creates an undeniable barrier, between expanding the cultivation of Hemp within the UK, and will need to be revised if the country can become self-sufficient rather than placing a reliance on a worldwide chain of imports.

The potential for growing, rather than extracting, to create construction materials is exciting; this seeks to usher in a new period, where land is there to become a source of fertility, rather than one for commodity.

Compared with the materials currently used within the UK construction industry, Hemp is regenerative and can be a carbon negative crop. This means that, rather than being a source of environmental degradation, the crop can act as a filter for the surrounding area, absorbing carbon whilst it grows and becoming a natural method of ridding the soil of toxins. This helps prepare the land for potential further use to grow crops without being as reliant on fertiliser, a material that promotes an exchange between human and non-human use. Additionally, the growing of Hemp becomes one which can become generous to its surroundings; it can become a hub for biodiversity, prompting insects and birds to come into the area. Imagine this world as one in which the growing of products aids the surrounding area, rather than depending on baseless extraction.

This natural attribute could herald a new era, away from relying on extraction of the ground beneath our feet for materials, and instead to work with the land itself. Regenerative design could change the landscape of the UK, and help promote a vision of a greener, more ethical form of construction. Through advocating for a more structural, ethical framework for Hemp reform, the building and rebuilding of our cities could expand organically, creating a mode of living and learning from the land around the country.

Within this context, there could become a vision for how Hemp reform could provide the basis for a restructuring of the separation between rural and urban communities, looking at how the emerging material and its application could become one for the education needed to implement a just transition to a sustainable future.

In place of land becoming priced, of commodifying both the built environment and the resources which constitute it, there could become provision for a yearly yield. This yield would dictate the expansion of the site, rather than a placing a dependency on extraction for materials. The harvesting and growing of Hemp could create a local economy and newfound employment, where material production becomes useful not only for the construction of homes, but for the health-based benefits of the crop. Hemp has many uses; as a crop, it creates the option for a regenerative form of farming practice. Seeking to build on established companies, Hemp farming could become co-operatively run and provide the basis for longer term growth.

Currently, our relationship to materials and production is through the means of; to paraphrase Marx, we have become invisible to the things we make. Nowhere is this more apparent than within cities in the UK, in which new build developments spring up, all clad a safe shade of brick. This is exemplified by the construction hoardings which pop up around each city, creating a boundary between the construction project and the local communities.

This focus on integrating the community back into the harvesting of Hemp could not only instate local forms of farming and ownership, but also to help heal the disconnect between production and consumption. This growth of materials could provide a connection between productive landscapes and a just transition, providing precious cultural insights which will help make a sustainable future easy to understand, walk through and take delight in.

The attachment, between source and use, creates a newer, home-grown form of construction. In place of noise, pollution and extraction, there will be tranquillity, increased biodiversity and routes in and around the ongoing construction. By rethinking our relationship to materials, one currently built on foundations of greed and excess, we can start to restructure our relationship to buildings themselves, questioning the nature of practice and who, why and how we build.

Hemp can provide the catalyst for social change and environmental within an area, providing a space where citizens can go and become immersed in the processes of production. A nature-led form of regeneration will not only establish a move away from our fixation with concrete, but also would create a calmer, kinder, more sensitive form of construction. The future of fields could be on our doorstep, in an emerging neighbourhood round the corner, all it needs is structural reform, and growth, to happen from the ground up.

Will Hayter is a Freelance Writer and Designer from London. He is currently pursuing an MA in Architecture at Central Saint Martins, exploring the role Hemp could play in the redevelopment of our cities. Tweets @w_hayter