In November 2020, Oregon became the first U.S. state to legalize the use of hallucinogenic mushrooms after voters passed a measure authorizing the use of psilocybin in certain settings.

Measure 109, which passed with 55.75 percent of the vote, gave the Oregon Health Authority (OHA) the power to license and regulate the manufacturing, transportation, delivery, and sale of psilocybin products and provision of services.

Adults aged 21 years and older are now legally able to consume psilocybin in state-regulated centers while under the supervision of licensed facilitators and guides. Psilocybin (also known commonly as shrooms, or magic mushrooms) remains illegal for retail sale and recreational use in Oregon.

Given these legal specifications, it is reasonable to view the measure as legalizing psilocybin-assisted therapy, rather than psilocybin itself. However, “therapy” holds a flexible interpretation in this instance, as all adults are legally allowed to access psilocybin services regardless of whether they have a mental health diagnosis or other therapeutic intentions.

Given these legal specifications, it is reasonable to view the measure as legalizing psilocybin-assisted therapy, rather than psilocybin itself. However, “therapy” holds a flexible interpretation in this instance, as all adults are legally allowed to access psilocybin services regardless of whether they have a mental health diagnosis or other therapeutic intentions.

Such inclusionary parameters are particularly noteworthy, as they diverge from much of the psychedelic industry’s focus on psychedelic-assisted therapy for the treatment of specific mental health conditions. Many people may have predicted that the legalization of psychedelics would follow the same regulatory trajectory as cannabis, in which U.S. states legalized the drug for medical use before permitting recreational access. Measure 109, in contrast, blurs the recreational and medical divide by offering adults access to psilocybin without needing to provide a doctor’s note.

For Tom Eckert, the ballot’s sponsor, this deviation from the norm was on purpose. Although the measure was intended and drafted for people who want to use psilocybin for therapeutic purposes, its legal structure allows it to function outside of what many consider to be a broken Western mental healthcare system by adopting a proactive approach to wellbeing.

Critics of Measure 109, like the Oregon Psychiatric Physicians Association, cite this very disengagement with the medical system to explain why the new law is potentially dangerous. For example, people who want to become licensed guides do not need any medical experience. Nonetheless, many training programs are still choosing to only enroll mental health professionals.

Psychedelic Guides and Psychedelic Assisted-Therapy

To earn their license, facilitators must complete a minimum of 120 hours of training and 40 hours of hands-on experience from a state-approved training program. The OHA has outlined specific topics that all training programs must include, including ethics and responsibility, consent, dealing with challenging trips, and general facilitation skills. Except for these components, training programs have significant flexibility on what they can include in the curriculum.

Jason Foster, a psychedelic educator who helps lead training sessions, told the Seattle Times that trainings mainly focus on “how to do a really thorough screening, how to help a client refine their intention for the journey that they’re going into, and giving [clients] the tools and knowledge about what to expect as they go into the journey.”

Psychedelic-assisted therapy traditionally follows a preparation-dose-integration structure that is modified based on a chosen psychotherapeutic approach, all of which tend to depend on the mental condition being treated. Oregon will also require facilitators to include preparation and integration sessions.

Before undergoing a session, participants are first screened for the physical and mental comorbidities known to jeopardize a positive psychedelic experience and long-term therapeutic benefits. For example, although research increasingly substantiates the efficacy of psilocybin for depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, and substance use disorder, it may worsen the symptoms of other mental illnesses such as bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. Physical conditions known to be a direct concern for psilocybin use include high blood pressure, diabetes, heart disease, and renal disease, among others.

The OHA has spent the last two years finalizing the ballot’s regulatory framework after its passage in November 2020. The department did not start accepting applications from psilocybin centers and guides until January 2023 and only approved the nation’s first psilocybin manufacturer license in March 2023. As a result, psilocybin is not expected to be legally available in Oregon until Summer 2023.

As of April 10, a total of 259 license and worker permit applications had been submitted to OHA for review.

Although now legal, adults may experience financial hurdles when seeking provide and receive psilocybin services. Since psilocybin remains federally classified as a Schedule 1 drug, insurance will not cover any related expenses. A single supervised session is expected to run an upward of $1,000. Training programs currently cost between $8,000 to $10,000 USD.

Psychedelic Legalization Across the U.S.

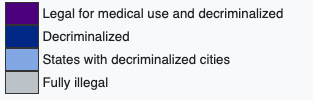

Psychedelic mushrooms are already decriminalized in several other cities and jurisdictions in the United States, including Oakland, California, and Washington, D.C. However, as the first state to completely legalize psilocybin, Oregon has become a case study and potential role model for other states who may be interested in expanding access to psilocybin or other psychedelic drugs at the local level.

As state senator Jesse Salomon, who is spearheading efforts to legalize psychedelic-assisted therapy in his state of Washington, explained to Seattle Times, “One thing we did — that I think was genius — is let Oregon go first, and then we’ll just learn, either adopt what they did or learn from their mistakes.”

In November 2022, Colorado voters approved a law similar to Oregon’s that allows for licensed “healing centers” to provide supervised access to the psychoactive components of fungi. In March 2023, state senators authorized the development of an advisory board to oversee the framework for its legalization. Colorado was one of the first states to legalize the recreational use of cannabis in 2012.

Moreover, lawmakers in almost a dozen other states have also introduced some form of psychedelic legislation for the 2023 session. At the current pace, it seems likely that psychedelic reform – an inconceivable debate several years ago – will continue to gain political momentum in the United States over the next several years.

Hannah Barnett is a medical anthropologist based in London. She specializes in psychedelic research and is passionate about the intersectional between drug policy, social attitudes, and culture.