What’s the political landscape for cannabis policy reform in Italy? After an Italian court recently ruled that categorizing hemp flower as a narcotic was ‘absurdly restrictive’, will a new bill on cannabis gain enough support to pass through the country’s legislature?

On February 24th in Rome the association Meglio Legale (‘Legal is Better’, ed) held its first public meeting due to open a nationwide debate in Italy about a new popular initiative bill on cannabis legalisation. Divided into three pieces, the bill aims at widening the use of medical cannabis (currently allowed under very strict conditions), at recognizing the existing cannabis industry in the country and, last but not least, at legalising personal consumption. This proposal would be the umpteenth attempt of the association, which already promoted a referendum in 2021 that didn’t make it to the ballots due to the Constitutional Court’s ban in February 2022.

“We’re surely aware that right now Italy has its most prohibitionist government ever”, Antonella Soldo, Meglio Legale’s coordinator tells me, “But there’s a higher risk to silence ourselves if we don’t deploy all the means we have to achieve our goal”. The bill has indeed to be approved by the Parliament, under Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni’s strict control, and Soldo happens to know the few chances her organisation has in the short term to succeed.

OPPOSITION FROM (MOST) ANGLES

Meloni has always opposed any drug liberalisation, and in fact when Soldo and her organisation were collecting signatures online for the aforementioned previous referendum she referred their efforts specifically as “a crazy message”. However, her objections don’t extend to medical cannabis, as the Defence Minister Guido Crosetto proudly announced the production increase in cannabis-based medicinals by the army three days before Meglio Legale’s public meeting.

“But on anything else, the dialogue is closed, even though we tried to approach them,” states Soldo, whose stance on the ruling Italian far right, “extremist, populist, anti-aborton”, goes along with the knowledge that currently without its voters support, nothing can be done. “We did a poll before the [last] referendum was blocked by the Court: 40% of Meloni’s voters were in favour of it”, she says, blaming the fact that they keep supporting Meloni due to “a lack of knowledge”.

Soldo doesn’t want to say that cannabis reform is a left-wing issue, but nevertheless it’s perceived as such by the vast majority of right-wing voters. During the referendum campaign Soldo didn’t refrain from taking pictures with Riccardo Magi, leader of the radical-liberal +Europa party, whom she counts among “our historical friends”, alongside politicians from other very liberal parties, like Volt, or more leftist like Possibile or the Verdi. But, Magi and his party are probably more friends than the others, due to a common background rooted in years. Soldo did her civil service in Associazione Luca Coscioni, a civil rights group historically linked to the Italian radicals. Indeed the debate over cannabis during the referendum campaign, ran parallel to the one on euthanasia, another referendum (also blocked) that had been proposed by many associations, the most prominent among them linked to the same radical environment. Soldo says this is a coincidence, “we had the unexpected opportunity to collect the 500,000 signatures online and we did it”, but that coincidence was surely favoured by years of common networking.

These close ties to the radical environment can create problems for those proposing cannabis reform when it comes to persuade other willing political forces to join the efforts, engendering mistrust. Carlo Calenda, leader of the biggest liberal party in Italy, Azione, has several times expressed doubts on the issue. “We struggle to make Calenda understand that this is a liberal and anti-Mafia battle”, tells Soldo. Indeed Calenda’s bid to include +Europa in his coalition of power is failing also for similar reasons, on the civil rights grounds.

The left’s white whale, the Partito Democratico (Democratic Party, ed), has often had its members promising to put the cannabis issue at the top of its priorities: the newly elected Party Secretary, Elly Schlein, included the issue in her program, after lobbying from Meglio Legale. However, in the former legislature, even though the Democrats’ votes combined with the centre-left Movimento 5 Stelle’s (Five Stars Movement, ed) votes could have allowed it, neither the first, nor the second biggest left-leaning party felt the urgency to pass a law on cannabis. “It’s not the Church’s fault, that’s populist excuse for everything”, comments Soldo when asked if 5 Stelle’s leader Giuseppe Conte’s and the then democratic leader Enrico Letta’s relations with the Vatican hierarchies influenced their choice to not actively support the battle.

Noi intanto ci preoccupiamo di non far ridere le mafie.

La legalizzazione della cannabis sottrae terreno alla criminalità organizzata, mentre alzare il tetto al contante e smantellare il codice appalti la agevola.

Son scelte. #MeglioLegale

— Elly Schlein (@ellyesse) January 25, 2023

Moreover, it was not a right-wing controlled Court that blocked the referendum in 2022, but a centre-left one, chaired by Giuliano Amato, former socialist Premier and one of the Partito Democratico’s founders. “A mixture of reasons allowed Amato to block the referendum, mostly legal quibbles. But, as the Italian Constitution allows only popular referendums, if you cut a piece of law it becomes puzzling. A proactive referendum would be a suitable option for democracy”, states Soldo, “Amato is much more an enemy than Meloni herself”.

However, the blockage imposed by the Court ignited mistrust in institutions in Italy’s youth. Luca Biscuola, 20, activist and former secretary of Milan’s Enzo Tortora radical association by the time of the Court’s ban, doesn’t hide his anger:

“Many of us believed that the people would succeed where the Parliament couldn’t. When the Constitutional Court President rejected the proposed amendments and blatantly lied about the eventual consequences during a huge press conference, the only ones who lost all the trust were the associations that had gone through so much to grant us a vote. A political work of art gently offered by the highest Italian court”.

On the other hand, Fabio Tumminello, 30, local spokesperson of Possibile in Turin emphasizes the previous lack of action of the Partito Democratico on cannabis:

“It hasn’t actually done much about the referendum battle. Excluding some initiatives by militant supporters, the party has not taken any position on the matter and this a clear sign of the deep divergence of opinion that continues to exist within the party on ethical issues, ranging from cannabis to euthanasia. As a former militant supporter in this party, I’m not surprised, because, since its origins, it was born to be a synthesis of different and often conflicting political experiences”.

THE CANAPA MUNDI CASE

Regardless of whether the cannabis issue will be a win or a loss for the liberal parties, this disconnect on cannabis is also indicative of a wider fracture between the youth (one out of three young people in Italy have tried cannabis at least once) and the institutions. New ways to build democracy, like the ability to collect signatures online (firstly trialled for the cannabis referendum) aren’t enough to change the spirit of a country that is moving every day more and more towards conservatism.

Even past achievements, like the law that enabled the selling of hemp flower or ‘cannabis light’ (Canapa, ed) for personal consumption in 2016, could be close to being called into question by the new Cabinet. The Italian Canapa industry, made up of over 12,000 workers and 3,000 companies, is indeed one of the clearest modern examples of Italian family-owned small businesses. Recently in Rome, on February 17-19, these producers held the 8th edition of the Canapa Mundi festival, where they showcased their products and industrial achievements.

Police raided the festival each day it took place, performing strict controls and searches and handing out fines for any small step out of line. Drug dogs walked down the corridors during the busiest hours of the festival, causing the outrage among the showcasers. “We’re all professionals and we pay taxes. We work regularly but we’re treated like drug dealers”, one of the entrepreneurs involved in the festival shouted at the officers, after having part of his products seized for ‘further controls’ by the police.

View this post on Instagram

Who exactly gave the order to storm a perfectly legal festival is unknown, which is pretty staggering, as eventually it was admitted that no large amount of contraband was found, despite all the meticulous controls. Police in Italy are under the control of the Interior Minister, namely Matteo Piantedosi, a man of the Lega (League, ed), Matteo Salvini’s party and member of Meloni’s coalition. However, there’s no certainty that the operation was ordered by a politician. “We cannot know who was behind it, but one possibility is that the police authorities wanted to impress the new government by showing themselves ready to act”, comments Soldo, who has been the public voice of the producers’ outrage on the national media outlets.

This signals that with this government a new environment is in place, and the attitude of right-wing supporters can easily be summarised by Salvini’s famous words “è finita la pacchia” (‘the party is over’), said towards all the liberals and leftists, seen as promoters of the ‘moral decadence’ of the country.

UNDERSTANDING THE ITALIAN RIGHT’S VIEW ON CANNABIS AND DRUG POLICY

The Italian right’s current drug policy has been influenced by ideas promoted by San Patrignano, a long-standing addiction recovery community whose methods have historically been a “right-wing alternative” to Gruppo Abele, a pro-legalisation NGO operating in the same field. San Patrignano gained popularity during the 80s and 90s for claiming to take care of people addicted to drugs by using paternalistic and simple methods without any mediation for preventing withdrawal symptoms at their rehab centers. This made San Patrignano popular with the public and gained them a political network that they maintain today.

The right-wing has been one of the political groups most seduced by San Patrignano, and in the fact the former Health Councilor of Lombardy, a centre-right rampart, was Letizia Moratti, a historical donor to the addiction treatment centre. Essentially, knowing San Patrignano’s stance on any drug issue means knowing the right-wing one as well.

When in 2019 the Court of Cassation ruled that of the selling of cannabis-derived products was illegal, the community released this declaration:

“For 90% of the young people present at San Patrignano, cannabis was the gateway to the world of drugs and its danger cannot be trivialised. Instead of thinking about useless legalisation, we should focus on prevention and a greater commitment on the part of the adult world in setting positive examples to our young people”.

Dismissing any calls for legalisation as “useless” and a calling cannabis a gateway to stronger drugs has been a right-wing trope for decades, which can be contrasted to the left-wing’s emphasis on “taking money away from Mafia”.

San Patrignano can effectively be seen as the right-wing’s drug policy think tank. They’re so entrenched that when in 2020 a Netflix documentary, SanPa: Sins of the Savior, questioned the methods used in the community and shed light on old violence and abuse cases that took place at their facilities, Meloni and Salvini ran to give their support. “I have been to San Patrignano many times and I am angered by this debate, Vincenzo Muccioli (the founder, ed) was an extraordinary man”, told Meloni. “Vincenzo Muccioli was defamed”, stated Salvini.

Moreover, it’s not just Meloni and Salvini’s opposition to cannabis that can be explained by the right’s ties to San Patrignano, but maybe even Calenda’s, the liberal strongman blamed by Soldo for not joining the battle. During the last February 12th-13th regional elections in Lombardy, the former Councilor Moratti changed political side and ran as Azione’s candidate for the Presidency. Even though the drug issue was not really at the top of the agenda during the campaign, it also would’ve been hard for Calenda to go public in favour of cannabis while his party is full of former centre-right politicians (not just Moratti) that on this issue share the exact same view of the current Government.

Giuliano Amato’s background is also linked in a certain way to San Patrignano, as his political leader during the 80s in the then ruling Partito Socialista (Socialist Party, ed), Bettino Craxi, was a huge supporter of Muccioli’s actions and he made with him what journalists then called an anti-drug agreement which brought Italy into the wave of the “War on Drugs” kicked off by the US in the 70s.

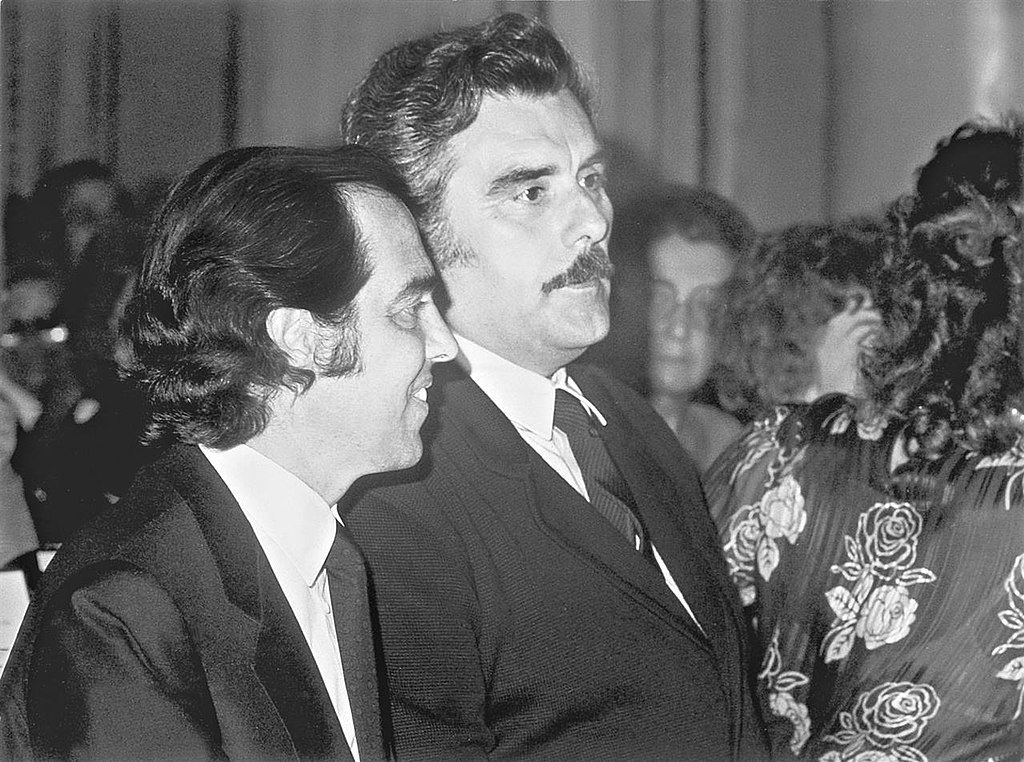

Vincenzo Muccioli, founder of SanPa, with Gian Marco Moratti, former husband of Letizia Moratti in 1985

HARD TIMES FOR CANNABIS LEGALISATION

Given the scenario depicted, you don’t need to be a genius to understand how difficult it is today to imagine a success in the short term for Meglio Legale and the other actors in the struggle for legalisation. “We will win”, states Soldo in a Che Guevara-style impetus of self-motivation, but “when” is a question she’s not able to answer.

The fact that according to Soldo, 40% of Meloni’s voters were allegedly in favour of cannabis has positive and negative aspects. It testifies surely that the majority of Italians would vote yes to a possible referendum, but at the same time it shows how they don’t care enough to impose this issue on the political agenda. Neither does it seem the left voters will do so, if we take into account the long-time inactivity of the Partito Democratico itself. What Soldo wasn’t able to hide is the fear of getting lost in silence. When asked if she agreed that the cannabis issue moved lots of votes, she said ‘no’, which could be a damning sign for the current legalisation movement, because, using the traditional approach of political economy, politicians are motivated to shape policies by their own interest, and it’s in their interest to win votes.

If cannabis is not able to inspire votes, politicians will never be pushed to act. Indeed, although legalisation has yet to materialize, the liberalisation of cannabis is a de facto condition no one actually cares about. Action by simple lobbying is not enough, because this issue is also about a cultural paradigm unwilling to recognize the existing situation under the current the law. It’s a question of ethics as well, and it goes without saying that the eco-system of Meglio Legale currently represents the most radical-liberal spot in the Italian political landscape. Free-market, free-choice, free cannabis, they’re all entrenched together, as Soldo’s statement reveals, “Ideally, I would rather have a free market for cannabis than a State monopoly”.

The real issue, then, is that currently the Government and the legalisation activists are speaking a totally different language and, for now, no one has been able to find a good translator.

Dario Pio Muccilli is a political science student and freelance journalist working between Italy and France as foreign correspondent for english-speaking media outlets. Tweets @dario_muccilli