DMT is well known for being one of the most potent psychedelics out there, capable of providing users with profound spiritual breakthroughs. There’s no surprise that this has led to it attracting nicknames such as ‘the spirit molecule’ and ‘fantasia’.

Despite these recreational connotations, DMT is also firmly on the radar for those interested in psychedelic therapeutic advancement, with the first clinical trial of DMT-assisted therapy having been launched in February 2022. Interestingly, historical uses of the drug also had their roots in the therapeutic context. With that, let’s take a look at the curious history of DMT…

What is DMT?

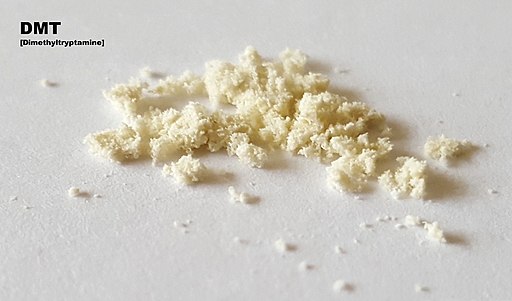

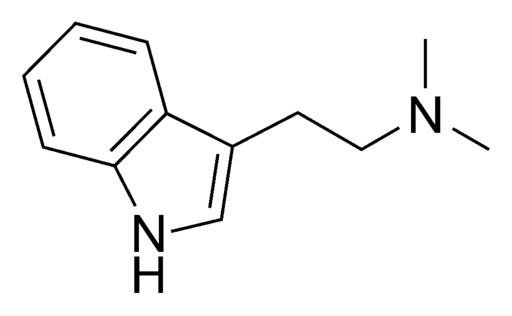

DMT, or dimethyltryptamine as it’s more professionally known, is a tryptamine-based botanical hallucinogen that is structurally similar to both LSD and psilocybin. The DMT molecule naturally occurs in a number of plant and animal species, however it can also be synthesised in a lab. The drug is perhaps most well known for its ability to create intense visual and auditory hallucinations which can cause users to experience profound spiritual breakthroughs. Many users report entering ‘other-wordly’ dimensions and interacting with entities that are hard to put into words (sometimes called Machine Elves).

As ethnobotanist Terence McKenna described in an interview:

“I encounter self-transforming elf machines, which are creatures, entities perhaps, although they’re not made out of matter. They’re made out of, as nearly as I can figure it out, syntax-driving light.”

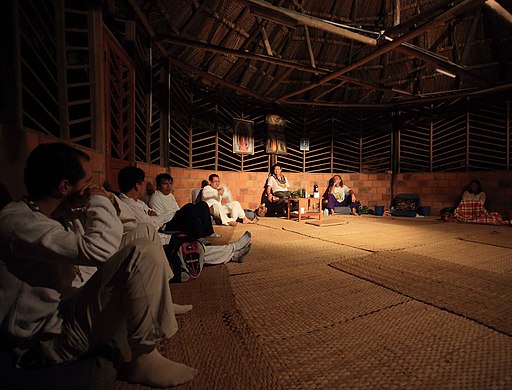

Of course, DMT has physiological effects too. These can include increased blood pressure and heart rate, nausea, and dilated pupils. For the most part, the duration of effects from DMT are dependent on the way it’s used. Many users prefer to smoke DMT via a pipe or joint, however it can also be injected, snorted or ingested in the form of Ayahuasca, a brew made from the plants Banisteriopsis caapi (which contains harmine) and Psychotria viridis, which has naturally occuring DMT.

The effects of the drug are felt almost instantaneously, within 10-60 seconds. However, a DMT trip is usually pretty short and intense, with effects lasting for around 15-20 minutes. Despite this users have reported that DMT experiences can feel like they last hours. It is important to note that this is not the case for ayahuasca. An ayahuasca trip can last as long as six hours, and its effects may persist for even longer. After consuming the ayahuasca brew, effects are typically felt in between 20 and 60 minutes.

As with every substance, it is important to be aware of potential side effects. Those with a history of mental health conditions should be careful when deciding to use DMT, as this may exacerbate the likelihood of a poor experience. Therefore, it’s a good idea to make sure both set (mindset, thoughts, expectations) and setting (environment and social setting) are right before journeying with DMT.

The history of DMT

The roots of the DMT molecule have been traced back to pre-Columbian South America, where ayahuasca was used for shamanic purposes. In 2010, José Capriles, an anthropologist at Penn State University, published a paper presenting the discovery of a 1,000 year old shamanic pouch which contained a number of psychoactive substances such as psilocin and DMT. It’s believed that the contents of the pouch may have been used for ayahuasca ceremonies conducted by South American shamans.

However, DMT only started to be discussed academically in Europe and North America in 1931, when German-Canadian scientist, Richard Manske, first synthesised the compound in a lab, although he never studied the drug’s pharmacological effects. In 1946, microbiologist Oswaldo Gonçalves de Lima discovered that the DMT molecule occurred naturally in a variety of plants.

Ten years later, a breakthrough occurred with the discovery of DMT’s psychoactive properties. In his paper “Dimethyltryptamin: Its Metabolism in Man; the Relation of its Psychotic Effect to the Serotonin Metabolism”, Hungarian chemist and psychiatrist Stephen Szára administered 20 healthy volunteers with an intramuscular dose of synthesised DMT. From this research, scientists were then able to determine the psychoactive properties of the molecule and its short trip duration.

This helped to pave the way for a small number of DMT studies that used human participants from the 1950s-1970s. At the time, scientists proposed that the powerful psychoactive effects of DMT (and other psychedelics they were studying) could help both provide a model of psychosis, as well as potentially treat brain disorders.

Moving into the 1970s, the tone shifted from one of discovery to one of panic and prohibition. The introduction of the UN Convention of Psychotropic Substances in 1971 brought into force a control system on psychoactive drugs, prohibiting their possession, sale, purchase and distribution. Many psychedelic drugs, including DMT, were scheduled as having no medical benefit, despite prior research suggesting otherwise. For DMT, the Convention signalled nearly a 20 year halt on clinical research.

However, the 1990s launched what is known as the ‘psychedelic renaissance’ with the first federally approved psychedelic study since the 1971 ban, which took place in 1994. Dr. Rick Strassman’s study explored the tolerability and subjective effects of DMT in humans, and documented the DMT experience in his book “DMT: The Spirit Molecule”.

Dr. Strassman’s study is credited with putting DMT and psychedelic research back on the map, although it was anything but an easy journey. It took Dr. Strassman two years to overcome the regulatory hurdles imposed by the 1971 convention. This included seeking federal approval and difficulties finding research-grade DMT.

Chemical structure of DMT

This study opened the doors for a host of DMT research moving into the millennium. In 2005, Gouzoulis-Mayfrank et al. conducted a double-blind, cross-over study which explored the psychological effects of DMT and ketamine in 15 healthy volunteers. Similarly, in 2009, Dauman et al. explored the effects of DMT and ketamine on attentional function as a core cognitive symptom of schizophrenia.

Another breakthrough for DMT research came via Timmerman et al.’s research in 2018/19 which helped to investigate the mechanistic effects of DMT in the brain. Researchers noted that the results illuminated the potential antidepressant effects of DMT, helping to pave the way for research in DMT-based therapies.

Where are we now?

Despite the positive results of prior research, DMT remains a class A and schedule 1 drug in the UK. This means that it is illegal to possess, supply and produce DMT recreationally. In the eyes of the Home Office, DMT’s schedule 1 status means it holds no therapeutic value and cannot be lawfully possessed or prescribed. It may be used for research purposes, although a Home Office licence must be acquired, and this is no easy feat.

Despite the hurdles that research into DMT faces, the future still looks bright for DMT-assisted therapy. Last year, biotech company, Small Pharma, launched the world’s first clinical trial for DMT-assisted therapy for the treatment of major depressive disorder (MDD). Moving into February the company has now announced that the patient has been dosed in their Phase 1 trial of intramuscular and intravenous administrations of DMT. It’s hoped that this research will help guide future clinical development and commercialisation.

There’s no doubt that DMT has had a bumpy ride when it comes to research and its legal status. The recent surge in interest in psychedelics and psychedelic medicines has proved essential in kick starting new research avenues and applications for one of the most powerful psychedelics. Although research still faces a number of hurdles, it appears there could be a bright future ahead for DMT-assisted therapy.

This piece was written by Volteface Content and Media Officer Megan Townsend. She is particularly interested in the reform of drug legislation, subcultural drug use and harm reduction initiatives. She also has an MA in Criminology from Birmingham City University. Tweets @megant2799.

Featured image: ‘DMT idea’ by L.Brown, CC BY-SA 3.0