Statistical releases on drug-related deaths in the UK hold few surprises these days. So, it was with a heavy sense of inevitability that I opened the Office for National Statistics’ (ONS) latest update on drug death registrations in England and Wales.

Sure enough, the figures show another 2% increase in 2016, coming on top of an 8.5% increase in 2015. True, the rate of advance has slowed, but even if they were to flat line, the situation would still be unacceptable by any reasonable measure – the drug death rate in the UK remains more than three times the European average.

Why the relentless rise? When you ask anybody in public health, they will first refer you to the ‘ageing cohort’ of people who started using heroin in the 80s and 90s, whose bodies and minds are now inevitably succumbing to the ravages of decades of opiate misuse, and all the increasingly complex health issues that accompany it. Undoubtedly, this is an important part of the story. The new ONS figures show more than half (54%) of all deaths related to drug poisoning in 2016 involved an opiate (mainly heroin and/or morphine).

However, we must be cautious not to just explain away the situation in this way and leave it at that. This is problematic for two reasons. Firstly, it risks writing off a whole generation of extremely vulnerable people as lost causes. Bear in mind that the majority of these users have never been engaged with the drug treatment system, a fact that effectively sealed their fate. We must now reflect on why they were never engaged, and work harder in future to do so. We can make this work infinitely easier by restoring proper funding to our drug treatment services, and by removing the illogical and inhumane barrier to accessing them presented by criminalisation.

Secondly – and particularly pertinently in relation to this set of statistics – an over-focus on one substance risks blinding us to wider systemic issues. After all, the new ONS figures have in fact seen opiate deaths level off for the first time since 2012 – albeit still at a shockingly high rate. This halt may be related to the more widespread availability of take-home naloxone provided to vulnerable users by local authorities – one common sense harm reduction measure implemented, but many more evidence-based interventions, such as supervised injection sites, remain stuck in the starting blocks in the UK.

Meanwhile, the continued rise in drug deaths is now being driven by other substances, almost all of which are causing increasing harm. Deaths related to cocaine, in particular, rose 16% in 2016. Our drug strategy is failing across the board – not just on heroin. The same problems of criminalisation, stigmatization, lack of treatment funding, and enforced user ignorance dog our efforts to reduce harm from other substances as surely as they do for heroin. An enforcement-based policy framework that has allowed opiate deaths to spiral out of control has ample potential to facilitate the same disaster for other substances.

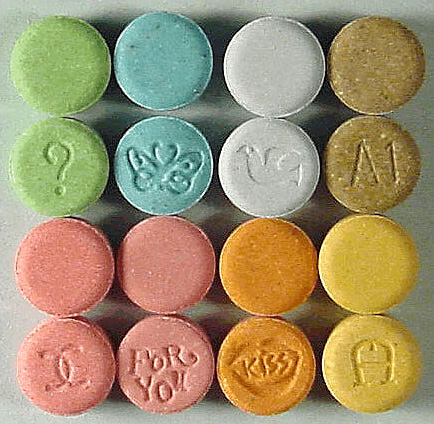

Source: Wikimedia commons

The issue of user ignorance, in particular, is one we can do something about. As recovering heroin strength has contributed to an increase in fatalities since the recent ‘heroin drought’, and as the increased MDMA content of ecstasy pills has fuelled more recreational drug deaths, so an increase in cocaine purity may be partly behind the pronounced increase in cocaine deaths in the new ONS figures. The pioneering work being done by The Loop at UK festivals this summer shows the way forward on this front, chemically testing drugs to allow potential users to make informed decisions and avoid super-strength or adulterated substances. Such services should become standard not just at festivals but in city centre nightlife areas too.

However, there is only so much that can be done to minimise the risk of harm at the user end. When drugs are supplied only by an unregulated, uncaring and unforgiving illegal market, their content will always vary unpredictably. Perhaps it is time for an open and adult conversation about the potential benefits and risks of modifying this situation.

Ed Morrow is Drugs Policy Lead at the Royal Society for Public Health. Tweets @edmorrow87