The Royal Society for Public Health and the UK Faculty of Public Health, two of the UK’s most highly respected public health bodies, have today called for the decriminalisation of possession of all drugs in a bold joint report, Taking A New Line On Drugs.

The report urges policymakers to shift away from treating drugs as a criminal justice issue and to move to a public health and harm reduction-based approach, recommending a ‘Portugal-style’ system of decriminalisation. To help achieve this, responsibility for drug strategy should be shifted from the Home Office to the Department of Health, the report adds.

The Royal Society for Public Health (RSPH) is an independent health education charity, consisting of over 6000 doctors and professionals from the public health community and can claim to be the oldest public health body in the world still operating. It describes its mission statement as ‘dedicated to protecting and promoting the public’s health and wellbeing’.

RSPH Chief Executive, Shirley Cramer outlines their position in the new report: “For too long, UK and global drugs strategies have pursued reductions in drug use as an end in itself, failing to recognise that harsh criminal sanctions have pushed vulnerable people in need of treatment to the margins of society, driving up harm to health and wellbeing even as overall use falls.

“On many levels, in terms of the public’s health, the ‘war on drugs’ has failed. The time has come for a new approach, where we recognise that drug use is a health issue, not a criminal justice issue, and that those who misuse drugs are in need of treatment and support – not criminals in need of punishment.”

Public support for the RSPH position seems widespread, after a recent poll of 2000 people commissioned by the RSPH and conducted by Populus found that 56 percent agreed that drug users in their area should be referred to treatment, rather than charged with a criminal offence, while under a quarter (23 percent) disagreed.

The Government will be hard pressed to leave the unequivocal call for policy change by the public health bodies unanswered. An initial response in The Guardian by a spokesperson from the Home Office offered vague words of support for the report in principle, but stopped far short of suggesting any action might be taken to move to a public health based approach:

“The UK’s approach on drugs remains clear – we must prevent drug use in our communities and support people dependent on drugs through treatment and recovery. At the same time, we have to stop the supply of illegal drugs and tackle the organised crime behind the drugs trade.”

Political support for the new report has, however, been forthcoming from other areas, with Liberal Democrat Health spokesperson and former health minister Norman Lamb hailing the report as a timely intervention, and reiterating his party’s support for decriminalisation of possession:

“Drug policy should focus on reducing harms from any drugs, legal or illegal, and this can be best achieved by focusing on diverting people from the criminal justice system. Continuing to criminalise drug users, blighting the futures of thousands of young people, is deeply flawed and has caused enormous harm.”

The report points to decriminalisation of drugs as a solution to the majority of public health concerns, with Cramer highlighting to The Guardian that the report’s suggestion that those selling or trafficking drugs should still be criminalised: “We think that people who are dealing drugs and the producers and suppliers absolutely should be prosecuted, but for people who have got a drug problem, why treat them differently from someone who has an alcohol problem or an obesity problem?”

A leader in The Times today goes further, noting that that the logical end point to a public health-based approach is not merely decriminalisation, but legal regulation, so that supply of drugs can be controlled and removed from criminal enterprise:

The Solution is not to return to the international drug wars of past decades, which proved unwinnable. It is to move towards legalised supply chains such as those allowed for cannabis in Uruguay and a minority of US states. The lesson of the drug wars is that a legal drug trade can hardly be worse than an illegal one.

Writing in The Telegraph, Christopher Snowdon, Head of Lifestyle Economics at the Institute of Economic Affairs, while heralding decriminalisation as an improvement on the status quo, is critical of the report in its failure to push for drug legalisation, stating that without legalisation, many of the problems that have taken root and flourished under prohibition would remain untouched.

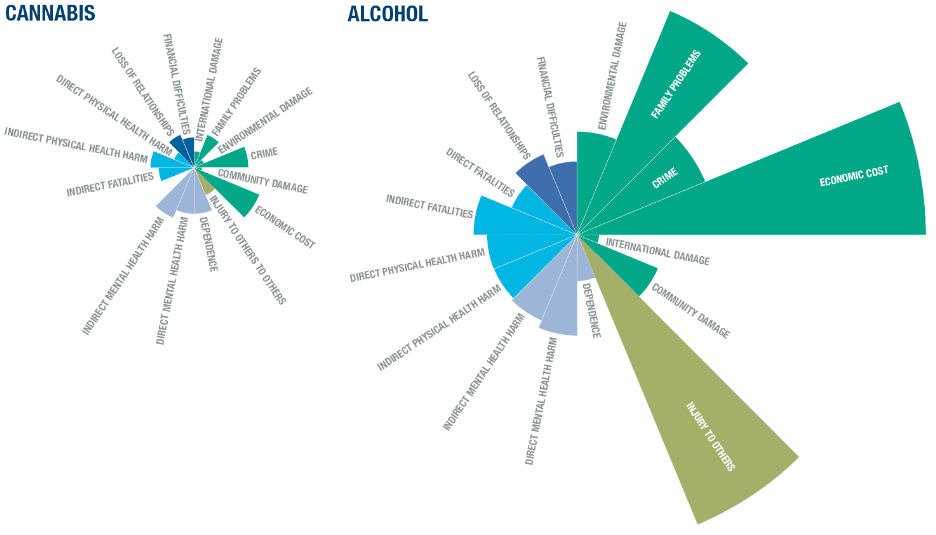

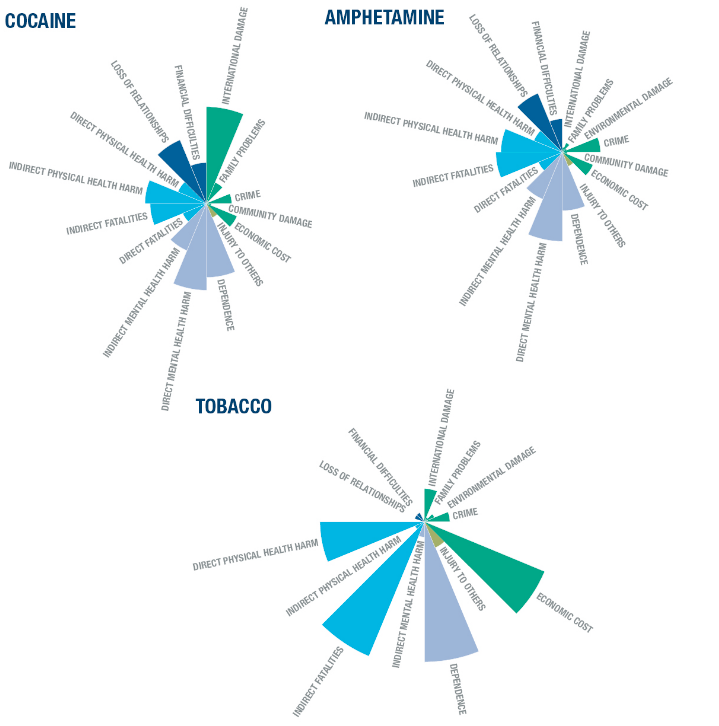

Indeed another key recommendation from the report makes clear the insufficiency of decriminalisation in comparison to legalisation at dealing with drug harms. The report states that evidence-based drug harm profiles should be used to inform policy, enforcement priorities and public health messaging and has created an online game for members of the public to test their knowledge of drug harms. However, the harm profiles for both alcohol and tobacco reveal these substances to be some of the worst offenders in certain measures. When laid out so clearly, merely advocating for decriminalisation of often less harmful drugs, as opposed to their legal regulation, undermines the RSPH’s recommendation of evidence-based policy.

While it is clear that decriminalisation is a good first step towards legal regulation and offers some clear and significant public health improvements, over exaggerating the value of decriminalisation as an end goal in and of itself comes with its own problems. Speaking to VolteFace, Alex Stevens, Professor in Criminal Justice and member of the Advisory Council on the Misuse of Drugs, cautions about over-enthusiasm for the successes of the Portuguese-style system, as he has noted previously:

“The authorities in Portugal are satisfied with the effects of their policy, which includes decriminalisation of all drugs for personal use. But they are not making any moves towards legalising and regulating the trade in such substances. From a public health perspective, this is problematic. Decriminalisation of possession leaves in place a criminal market that meets the ongoing demand. So users continue to face risks from products of unknown content, potency and purity. Violence associated with criminal supply is still a danger. Legalisation would probably reduce, but not eliminate, these risks.”

Sam Bowman, director of the Adam Smith Institute, is similarly sceptical: “Decriminalisation might sound like a stepping stone to full legalisation and regulation, but it’s risky. It doesn’t eliminate street dealing and doesn’t stop under-18s from getting access to drugs, which are two of people’s biggest concerns about legalisation, and it doesn’t allow us to encourage use of less potent strains of cannabis.”

If enacted poorly, decriminalisation could hamper further efforts for drug reform politically, and so the best course of action must be chosen wisely, Bowman adds: “Most people don’t differentiate between decriminalisation and legalisation in their minds, so there is little political advantage in going for decriminalisation – and if we do that and people do not see an improvement in the things that matter most to them, support for further drug reform will collapse.”

On legalisation though Stevens is measured, stressing that it is not without its own risks: “legalisation also poses problems for public health. Prices would tend to fall and legal drug sellers would have an incentive to increase consumption among heavy users. These are the people who experience most harm and who would provide most of the profits in a legal market.”

The heft of both such august public health institutions entering into the debate on drug policy should not be underestimated, as Neil Woods, former undercover drug police and chairman of LEAP UK states: “When a great institution like the RSPH presents work like this we all need to sit up and take notice. This report is thorough and the evidence clear. Drugs policy should be about drug harms not drug use. As a police officer on the front lines of the war on drugs I’ve seen the dreadful costs of trying to enforce the failed policy.”

The RSPH is a particularly booming voice to add to the clamour from other organisations, experts and members of the public calling for drug policy reform, carrying with it the weight of thousands of public health professionals. Governmental ears are only so deaf, sooner or later they will have to start listening to the advice being given on drug policy. When this happens though, is it too optimistic to hope it takes the best course of action, rather than what may seem the easiest?

Words by Henry Fisher, VolteFace Policy Editor