As a psychiatrist who is interested in psychedelic drugs, I’m probably qualified to say that, generally speaking, most people know very little about psychedelics, and what they do know is often coloured by years of politically-inculcated and media-perpetuated stigma.

So, it was refreshing to hear an informative and equipoised edition of Seriously… on BBC Radio 4 last night, entitled Psychedelic Science that sought to explore the state of the field today.

The programme started with some historical perspective. Prior to the 1970s, psychedelics (particularly LSD) were commonly used in Western psychiatry in drug-assisted psychotherapy for addictions, depression and anxiety disorders. They were considered to be safe and effective in medically controlled settings, with no risk of dependence, but it was noted that recreational use could lead to risky behaviours, especially in psychologically destabilising environments.

In the US, the 1960s saw the Vietnam war intensify and the rise of an antiwar and countercultural movement that tended to use psychedelics and cannabis in preference to alcohol and nicotine. It also included the LSD-acolyte and former Harvard researcher, Timothy Leary, as one of its spiritual leads. ‘Turn on, tune in, drop out’, Leary’s catchy précis of the psychedelic experience and the users’ reactions to it, encapsulated what some saw as a route to a self-reinforcing transcendence away from a sick, materially obsessed society, but others saw as a route into social idleness and psychological degeneracy. Never has there been a psychoactive substance that has seemingly generated such polar opposite opinions, as LSD.

Timothy Leary on his 1969 lecture tour, where he urged attendees to ‘turn on, tune in, drop out’ (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

By heavily criminalising cannabis and psychedelics, the Nixon administration gave itself legal sanction to criminalise the antiwar and countercultural movements. Partly because of this, and partly because of some concern for rare toxic reactions during recreational use, psychedelics were placed in Schedule 1, Class A of the UN convention on drugs, denoting that they had no accepted medical use and the maximum potential for dependence and harm. This was despite the research papers that evidenced their use in psychotherapy for mental health problems, and the lack of any evidence for dependence. A carefully orchestrated media campaign demonised the drugs as much as the movements that were associated with them. This legal classification was adopted around the world, including here in the UK.

Losing the Vietnam war in 1975, the US busied itself with a new war: on drugs. Drugs were, in Nixon’s own words, ‘public enemy number 1’. A whole generation grew up with the echoes of this political manipulation ringing in its ears, and concluded that psychedelics must be bad because they were told it was so, and told their kids that too.

As an aside, years later, in 1992, John Ehrlichman, Nixon’s advisor for domestic affairs at the time, confirmed at interview that the administration had intentionally lied about the harmful effects of various drugs to give them legal sanction to criminalise the anti war and counter cultural movements. But by that time it was too late. All medical use of psychedelics had long ago ceased, as had all research into their use.

So where are we, nearly half a century on?

Jamie Bartlett and Hannah Barnes, producers of this episode of Seriously… attempted to answer that question …and did a commendably good job.

Today, psychedelics are raising their heads from their social shackles. Psychiatrists and researchers looking for new paradigms in the treatment of mental health problems are looking to their predecessors’ use of psychedelics (and the empathogen, MDMA) in drug-assisted psychotherapy with interest.

The programme introduces Bill Richards, a psychotherapist in Baltimore sufficiently advanced in years to have experience of psychedelic assisted psychotherapy before prohibition, and the psychiatrist Roland Griffiths. Together, in 2006 at Johns Hopkins University in the US, they sought to test the active component of psychedelic ‘magic’ mushrooms (psilocybin) on healthy volunteers who had never taken psychedelics before. Griffiths was surprised to find that not only was the psychedelic experience well tolerated but that, even 14 months after the experience, 70% of the participants rated the experience as within the top 5 most meaningful experiences of their life, and 30% rated the experience as the single most spiritually meaningful experience in their life, ever. What was extraordinary was not so much the profundity of the experience per se, but that it lasted many months after the drug had left the body. This appeared to set aside psychedelics from almost all other examples of psychoactive drugs.

Spring Grove Hospital, the site of experiments into LSD assisted psychotherapy in the 1950s (Source: Forsaken Fotos)

Small scale trials in addictions and anxiety have followed, producing encouraging results. The team at Imperial that I am a part of, led by Dr Robin Carhart-Harris and Professor David Nutt, will shortly publish results of the first trial of psilocybin assisted psychotherapy in treatment resistant depression. Robin explains to Jamie that 2/3 of the patients in the study were depression free after 1 week, with 42% still depression free at 3 months. This is an open label pilot study, designed to show that the research is possible in principle. Whilst it may not accurately estimate the true effect size in the population of people with depression, it is certainly evidence that more research is needed.

There are difficulties with researching psychedelics, as Jamie explains. Firstly it is impossible to blind participants or the investigators. It is obvious to both participant and investigator when someone is on psychedelics. Secondly, the therapeutic effect is inextricably linked to the context it is experienced in. Provide a safe and supportive setting for a psychedelic trip, and you are much more likely to achieve a good therapeutic outcome than otherwise. But this inextricably interactive effect is problematic for modern trial designs, which seek to isolate a drug and test it solely for its therapeutic effect. With psychedelics you cannot do this. You have to consider the drug and the context together, or you miss the point. The psychedelic is a catalyst in a contextual substrate. Without that substrate, there is little effect. This doesn’t mean the research is impossible, but it does mean it requires a more flexible, and therefore less scientific, approach. Bill Richards explains the approach to supporting someone through a difficult experience with what, for me, is the most memorable quote:

“We often say that if during your psychedelic session some monster appears, then you want to say ‘well, hello monster, are you ever scary, what are you made of, why are you here, what can I learn from you? And you go towards that mental image, and then there is insight and then there is resolution and there is healing. On the contrary if you run away from it, it’s like running away from your own shadow. So you develop panic and paranoia and you might well end up in a psychiatric emergency room.”

That rings true of my experience as a psychiatrist as part of the team conducting the Imperial psilocybin trials. The people who report the most sustained benefit are those who have chosen to face their demons head on, and had the courage to laugh at them.

‘Well, hello monster’ – The Nightmare by John Henry Fuseli could just as well be depicting a difficult psychedelic experience (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

The therapeutic effect of psychedelics is not, however, the reserve knowledge of medical science. The programme went on to describe the UK Psychedelic Society, an organisation led by a gentle, unassuming man called Stephen Reid. In an effort to allow people to experience psychedelics legally and relatively inexpensively, he organises small group trips to the Netherlands, where psilocybin containing truffles remain legally obtainable. The programme followed some of the participants of a trip to Appeldoorn, an hour or so west of Amsterdam, where, in bucolic, serene surroundings, 16 people, supervised by 4 sober facilitators, took a dose of psilocybin containing truffles after signing a declaration taking full legal responsibility for their actions.

Here I can add a personal note to this piece. I was there in Appeldoorn too with Jamie. I’m interested in psychedelics and what they represent. I’m interested in the conversations people have with themselves, with others, and with their worlds. Within the detail of these conversations – our conscious experience and what we think about it – lie, in my opinion, both the problems that lead to some mental health difficulties, and the solutions to them.

I’m also interested in what Stephen Reid is trying to do. I have mixed feelings about it, because at one level I admire his aim to bring the beneficial elements of psychedelics legally and relatively safely to those who wish to try them. But at another level I am concerned that the scientific research I conduct with Robin and David, and which I care so much about, may be threatened by a blurring of the boundaries between recreational use and medical use and, critically, a conflation of the risks between the two scenarios. This is what happened before, in Timothy Leary’s time.

There are few risks when psychedelics are used in medical settings. They are remarkably safe, in fact. But in recreational circumstances, where you have no access to medical therapy, and an uncontrolled environment, it is more risky. Clearly this Psychedelic Society weekend was more recreational use than medical use, but it was certainly not the type recreational use that I have occasionally seen lead to admissions to the NHS psychiatric ward I work on in South London. Here, there was a single, known dose of a known substance amongst a group of people who were not only largely experienced in their use, but also, critically, had a shared common goal and had got to know each other beforehand. There were sober facilitators and observers to take any difficulties in hand and there was no mixture with any other psychoactive substance (alcohol was not allowed). Whilst some people had difficult times during their experience, every person rated it, overall, as a positive experience. And I suppose here is the nub of it. Experiences can be difficult and distressing, but what you take from them can be enlightening and positive. That depends on your attitude to the experience itself.

To that extent psychedelics aren’t some sort of panacea, and no one is suggesting they are. But if you are willing to go where they take you and, as Bill Richard’s describes, look your demons in the face with a curiosity and a friendly smile, you’ll most probably find they were never as frightening as you thought they were going to be. Our human minds have a fantastic ability for fantasy, and sometimes we believe the fantasies we create for ourselves.

Part of the mechanism of action of psychedelics is that they (probably) deconstrain and desegregate normal patterns of thinking and perceptual experience, so it is unsurprising when people under their influence struggle to put into words the experiences they are having. The experiences are often deeply emotional and meaningful in a way that transcends language, and becomes deeply personal. Here we perhaps transcend the ability of science to measure the effect. To this extent there is probably no fool-proof way around the problem that Jamie Bartlett has in trying to understand how psychedelic experiences might lead people to be less depressed, less anxious, or give up smoking. The brain is intrinsically difficult to measure, however we have more refined methods than we did 50 years ago. Still, as Griffiths puts it, ‘we are in kindergarten’ in our attempts to understand how the brain actually works, and how it generates consciousness.

With modern neuroimaging methods we can compare the brains of people in normal waking consciousness, and under the influence of psychedelics. Robin Carhart-Harris describes his team’s research at Imperial College London giving healthy volunteers intravenous psilocybin whilst they were in a fMRI scanner that was taking proxy measurements of blood flow in different parts of their brain. They found a reduction in blood flow in areas of the brain known to be responsible for high level integration of different facets of experience, and known to be involved in our capacities for self reflection and self definition. It is also an area known to be over-active in depression.

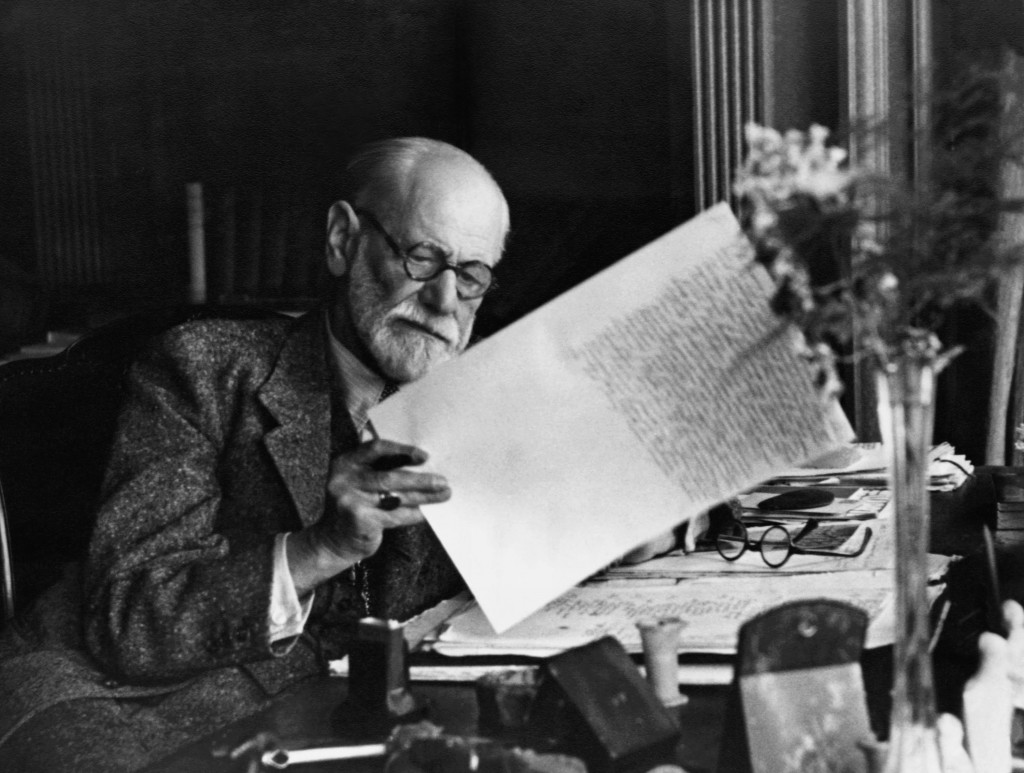

Freud termed this high level cognitive processing about our concept of self as the ‘ego’, and it is apposite in this context, that one of the first observations made in the 1940s by psychiatrists observing the effects of psychedelics on people was that they induced a temporary state of ‘ego-dissolution’. Something some of the participants in Appeldoorn were trying to get across, I think, was that their ‘thinking’ sense of themselves and the boundaries this tends to create between them and their worlds, dissolved away to leave a naked, more primal sense of existence. A state of existence which is not ‘thought about’, but simply ‘experienced as is’. Freed from the neurotic boundaries of thought, perhaps we are free to have the deeply personal experiences that some refer to as so beneficial, and perhaps the brain is free to rebuild the links between perceptions and conceptions in ways that are not so likely to lead to maladaptive patterns of behaviour (such as smoking cigarettes, or depressive ruminations). Perhaps.

Freud’s concept of the ‘ego’ has found an new context in the study of psychedelic drugs and their effects

The programme concludes by illustrating the pragmatic difficulties there would be in getting psilocybin and LSD onto the market. The cost is massive, and currently prohibitive. However the precedent exists with cannabis and so, one day, perhaps it will be with psychedelics. We are a long way off from that and, in the meantime, we need to make sure that the mistakes of the 1960s do not happen again and we proceed with a slow, meticulous collection of good quality evidence. That will take time but, I feel, it is time well spent. It was good to see a programme on psychedelic science that challenged the stigma surrounding these substances, and gave an equipoised presentation of the risks and benefits. I hope it’s the first of many.

I have to declare my own biases and interests here. I am interested in psychedelics. As a psychiatrist I think they deserve further research, and I am interested in doing that research. However I have no financial interest in them and have no links with private medical providers or the pharmaceutical industry. I only work in the NHS and at universities. I have not been paid to write this piece.

I conclude finally by pointing out that the only way psychedelics will ever become accepted as a medical treatment is through a change in the law. The Misuse of Drugs Act requires wholesale revision. I support VolteFace in their calls for a drugs policy that is focussed on scientific evidence and harm reduction, rather than political rhetoric and stigmatised heresay.

Dr James Rucker is a psychiatrist and honorary lecturer at the Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology and Neuroscience, King’s College London.

Seriously…: Psychedelic Science aired on BBC Radio 4 at 8pm, 7th April. It is currently available to listen to on BBC iPlayer.