In the low ethereal glow of a hotel bathroom, the dopamine flows. Two pairs of eyes meet across the bubbles, and serotonin streams like sunlight into the 5-HT receptors of the brains behind them. Oxytocin, and a shared sense of elation spreads through both bodies. Monika and Lars are more in love than ever, and they’re on MDMA.

Talking about it three years later, they dive animatedly into the sheer romantic joyfulness of the memory. He embellishes her recollections; she picks up the ends of his sentences. “There was nothing between us,” they explain, “it was like we were merged.” As they gush in their keenness to convey the importance they both place on that particular MDMA experience, there’s something oddly reminiscent of this video series of Ann and Alexander (Sasha) Shulgin, discussing their shared drug-taking episodes in the living room at Beckley Park.

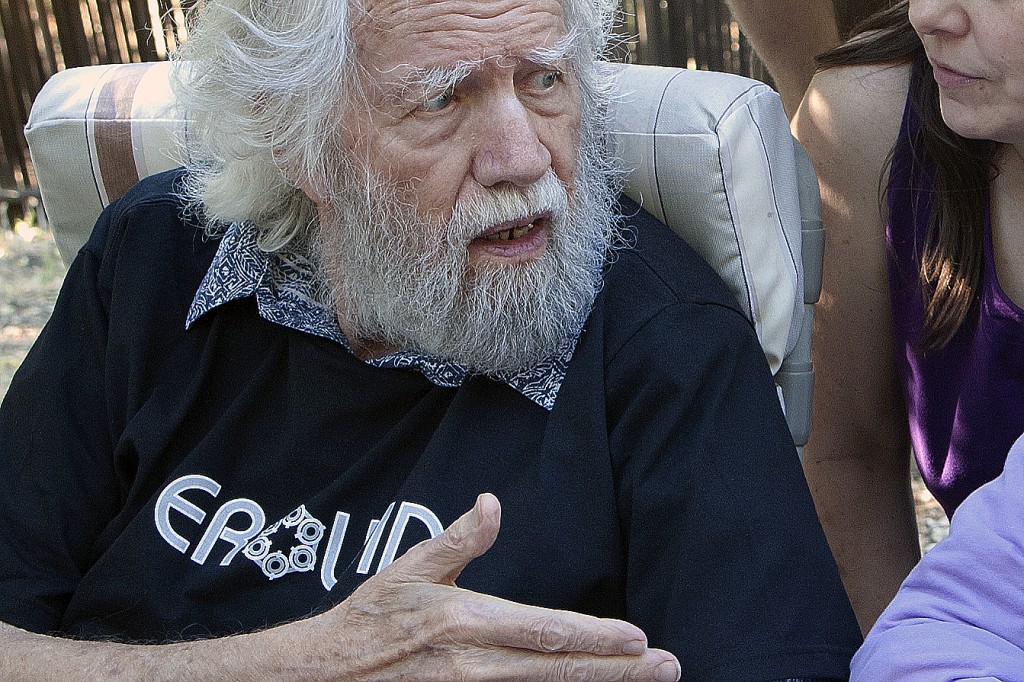

Famed for their chemical synthesis, self-trials and beautifully penned experiential treaties on hundreds of psychoactive compounds, the Shulgins are sharing anecdotes on a visit to fellow psychedelic researcher Amanda Feilding. Like Monika and Lars, they can be seen encouraging threads of the conversation through squeezes of their hands, lovingly correcting one another, finishing each other’s thoughts. Describing exactly the same chemical coalescence Monika and Lars experienced in the bathtub, Sasha, who was famously dubbed ‘The Godfather of Ecstasy’ wrote of an MDMA experience with Ann that, “underneath it all is the feeling that we both belong here, just as we are, right now” (PIHKAL: A Chemical Love Story, 1991, p.203).

But, doesn’t a normal couple, one that isn’t internationally celebrated for self-experimentation like the Shulgins, feel a teeny bit weird retrospectively fleshing out the minutiae of such an intimate moment for the eager ears of a third party (dictaphone in hand), particularly when that moment involves MDMA, one of the UK’s most strictly classified illegal substances? Not when it’s all in the name of psychological research. Monika and Lars are one of 10 couples who have been supplying qualitative data to Katie Anderson of London South Bank University, as part of her PhD project: “MDMA: the love drug.”

“Let’s take MDMA together; I want to love you even more.”

I caught up with Katie after she’d presented her preliminary findings at this year’s International Conference on Psychedelic Research, and here’s what I learned: she has coined the term the “MDMA bubble,” a dynamic which takes the form of a kind of protective casing a couple enters into together as they embark on their high. Having researched MDMA users more generally for her MSc dissertation, Katie was captured by the idea that some of its key effects, openness and empathy, are “the perfect conditions for romance – for crafting a relationship.” She has always seen MDMA as unique in providing a high accompanied by such a strong sense of connectivity: “the couple in the bathtub were experiencing a particular kind of ego dissolution.” Like the kind that occurs in the recent LSD Beckley/Imperial LSD studies, where “the normal sense of self is broken down and replaced by a sense of reconnection with themselves, others and the natural world”? “Yes, exactly! But they enter this space together.”

And how happy were the couples to talk, in general, about MDMA? “There was a range of attitudes, and degrees of openness – most couples were happy talking about their MDMA use with friends, but not with family or at work. None were involved in drug policy or advocacy etc., so there were different levels of comfort.” The interviews were semi-structured, meaning that they took the form of free-flowing conversations, punctuated by some staple questions and activities. As part of the interview process, participants brought 4-5 items (photos, keepsakes, words) that were reminiscent of their experiences.

The relics of romance included a brightly patterned hula-hoop and a set of photos from a party photo-booth, indicating that the festival atmosphere and its paraphernalia is complimentary, even conducive, to these romantic moments of intimate closeness.

Another interview activity involved the couples ranking the importance of their MDMA experiences in relation to other crucial events within their personal relationship timelines. Despite their wide range of differences in ages, financial circumstances, career choices, everyone agreed that they’d had a positive shared experience of MDMA, and that there is something uniquely special about the shared experience of taking it together, in love. 8/10 ranked their MDMA memories alongside the more archetypal fixtures of the amorous trajectory, like getting married and the birth of their children. (An emphasis which tellingly echoes Prof Roland Griffiths’ findings when he conducted a survey on the life-changing potential of psychedelics as part of the John Hopkins Psilocybin Research Project, in which a third of users attributed the highest degree of significance to having tripped on magic mushrooms within their lifetime.)

“I was worried it was just a chemical romance.”

Does MDMA ever create feelings from scratch? Katie mentions one volunteer, Nick, wondering if the heightened level of connection to his partner that he felt could prove “too good to be true.” However, along with many of the other couples, his recollections after the experience reflect a residual but enduring sensation of increased closeness. Like traces left by soap bubbles, most of the couples emerge from the cocoon of the MDMA experience noticing that their relationships are brighter and better than before. Katie evaluates these longer-lasting positive changes as being as “real” as any other relationship dynamics, despite having originated from taking MDMA.

In their seminal editorial; “MDMA, politics and medical research: have we thrown the baby out with the bathwater?” Beckley Foundation collaborators Dr Ben Sessa (University of Bristol) and Prof David Nutt (Imperial College) lament the fact that MDMA was made illegal by “single-minded politicians” in order to prevent an epidemic of people “writhing on the dancefloor,” and assert that MDMA-as-a-medicine has wrongly been “caught in the crossfire of the War on Drugs.” The jurisdiction has for, several decades, interrupted vital research into MDMA as a psychiatric tool. Sessa has more recently, and more viscerally, spoken out on social media against the blinkered political tendency to conflate the clinical administration of MDMA with recreational use when they should be clearly differentiated, asking whether cardiac surgeons writing papers on optimising the safety of medical procedures, would be hypothetically be obliged to nod to it, “if there was some weird recreational pursuit in which some people performed open heart surgery on their kitchen tables with rusty instruments” … Point made.

But, even at variable street-level purity and separated by a canyon from clinical conditions, it is remarkable that MDMA deepened interpersonal connections between 90% of Katie’s interviewed couples. These results indicate MDMA’s empathetic properties are so potent that, against the odds of the adulteration it incurs on the illegal market, and despite it being taken in a recreational climate, the potential benefits of MDMA are trickling determinedly into a proportion of couples’ lives and improving their relationships. In the context of our current drug culture, these results are surprising, but they befit MDMA’s singularly benign historic trajectory as a substance that initially entered the psychiatric arena in the 1950’s after having been found so incapable of producing any emotional effects other than compassion that the US Army deemed it to have no military use.

Other than Monika and Lars, who shared a bubble bath, what did the rest of the serotonin-crossed lovers get up to during their high? The anomaly within the research sample were one couple who “loved taking MDMA and going out to gigs,” but their experiences were “never deep, or life-changing.” More interestingly, nine out of ten couples found themselves indulging, unintentionally or intentionally, in MDMA’s therapeutic conversational properties. So is MDMA masquerading as a party drug, whilst offering these couples something much more beneficial? Katie finds one of her interviewees’ stories particularly symbolic in this regard; they dropped MDMA to dance, but inadvertently succumbed to its propensity to be therapeutic: “suddenly we were talking on the couch for the entire night.” About half the couples planned to take MDMA in a social setting, but then felt a desire to peel away from the party for some one-on-one conversation, inadvertently entering the “MDMA bubble” and plumbing new depths of their abilities to compassionately confide.

Emily and Dan “took MDMA for fun” initially but recall how this resulted in a mutual admission of infidelity. Despite it being “the worst stuff you could hear,” Dan recounts that, “it was as though every word she was saying made me love her even more.” Admitting infidelity during their MDMA experience helped the couple to reach a point of total honesty, such that, after a break-up, they felt able to heal the schism and return to the relationship secret-free. This sense of feeling secure within the drug-fuelled conversation no matter what negative memories or topics come up is the basis of MDMA’s use in psychotherapy, and was replicated by other interviewees: “one person’s going to be really honest and the other person’s going to listen and accept…I think that’s actually a very safe environment to chat through stuff”. For other couples, the use of MDMA to reach a state of conversational openness and mutual self-acceptance was deliberate. Mark and Jenny describe their use as “therapeutic” and walk through the streets of their city for hours “just dealing with all the issues that we have and just flowing with conversation”.

A lasting impression that Katie has taken from her interviews is that there’s “no typical MDMA user.” Users were a wide range of ages and took MDMA in a variety of settings: from the traditional club/festival venues to exploring urban and natural environments. As qualitative research into recreational MDMA use is so unwillingly funded, and consequently so rare, she feels privileged to have been allowed glimpses into “so many worlds.” But the vast majority of her interviewees were similar in one respect: they were recruited from MDMA/drugs subreddits, and RollSafe; online communities dedicated to sharing tips about illicit drug taking, and how to indulge in it, in relative legal and medical safely. Katie recalls being overrun with applicants, but that there was something special about the final ten: “the couples ultimately who took part in the study were all there because – if they wanted to make the time commitment and were brave enough to open up – MDMA was in some way important within their relationship, and they had something important to say.”

These are people who are trying to protect themselves as best they can, arming themselves before they drop with whatever information they can find. Before Sasha’s death, the Shulgins decided to disseminate their collected information about MDMA and other drugs for free: as it was illegal, they had to rely on the rave culture, “interested amateurs” – their purpose was to make sure that what had been discovered about the pharmacology and transformative properties of drugs “cannot be exterminated now.” The couples in Katie’s study are just such amateurs as the Shulgins wished to benefit. By researching and discussing their MDMA experiences online, they are sustaining an important legacy.

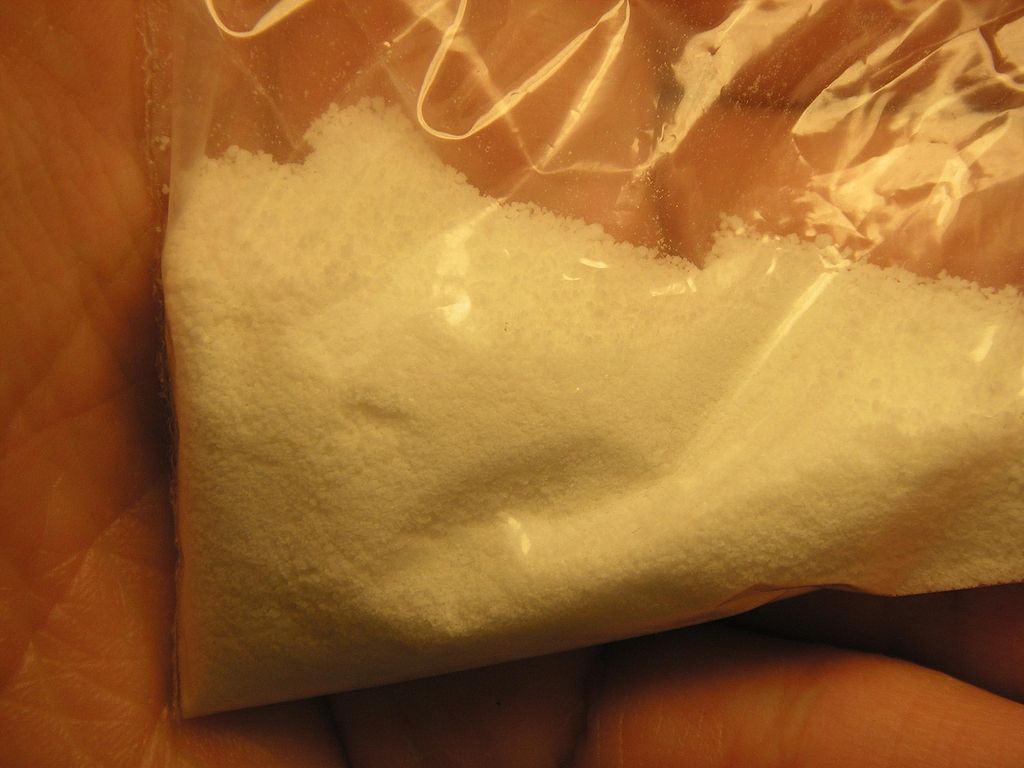

Although some of the experiences described by the couples indicate strongly therapeutic effects, a crucial distinction between MDMA therapy and recreational use is “that after 40 years of MDMA research, there has not been a single, serious adverse reaction,” following a clinically-administered dose of MDMA (Sessa, TEDx, Uni of Bristol, 17.45). All “ecstasy deaths” and associated media hysteria are born out of our current recreational culture, in which prohibition makes safety impossible because, “we’re in “the land of the blind,” grappling with assumptions and unknown adulterants, as VolteFace’s Policy Editor Henry Fisher observed after testing festival goers’ drugs with The Loop. The samples of “MDMA” taken by The Loop when they tested punters’ drugs at The Secret Garden Festival this July revealed that unregulated pills could contain anything from a lethally strong dose of MDMA, to concrete!

In his biting analysis of fabric’s closure earlier this month, David Nutt points out that “tragic deaths” are often caused by more toxic MDMA substitutes such as PMA and PMMA, which make their way into the hands of clubbers when the real deal is in short supply. Furthermore, a lack of regulation over the potency of MDMA, and insufficient harm reduction measures form a potentially fatal combination. This makes accidental overdoses, such as suspected for the two 18-year-olds who died after going to fabric, all the more likely.

Katie feels that MDMA can be “demonised and derided” in the mainstream media, and that the unlucky few for whom adulterated, black-market doses of the drug prove fatal are all too often made to stand for users as whole, framing recreational drug use as incompatible with a functioning society. The current propensity of Brits to blunder around in the dark ingesting unknown substances adds, unfairly, to the notoriety of “MDMA,” which is used by a sometimes unscrupulous media as a blanket term for its more toxic substitutes. This reaffirms our drug culture where talking about drug-taking is taboo, drug-testing in the UK has only just become a possibility and has taken years of hard work and careful planning to organise, and most safety-measures involve hearsay and guesswork.

One important thing to note is that all of the couples were only concerned with the illegality of MDMA at the beginning of participating in Katie’s research. Having sussed her out as a non-judgemental interviewer, collecting their subjective experiences with the spirit of an explorer, they focussed entirely on the way taking MDMA together had provided them with a unique platform to explore aspects of their relationships, upholding the Shulgins’ intentions that MDMA be shared and experienced and enjoyed safely regardless of its legality.

According to the 2016 Global Drug Survey results, UK clubbers take the most MDMA per night (up to half a gram), so Katie is doing vital work bringing the droves who take MDMA every week in the UK with no long-term adverse effects into the academic discourse. And she’s valiant for setting out to do this in a climate which is such a far cry from the pre-prohibition perception of MDMA, which, before the “war on drugs,” enjoyed a spell as a mainstay in couples therapy.

And, in step with Katie’s psychological research, MDMA couples psychotherapy itself is making a comeback: on August 2016, a couple took part in the first experiential treatment session of a new trial of MDMA-assisted Conjoint Therapy for PTSD, by our friends at the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies (MAPS), monitored by Julie Holland, M.D. Both the partner experiencing PTSD, and their significant other, will take MDMA, reaching a clinically-controlled, psychotherapeutically superintended version of Katie’s “MDMA bubble”; a safe space in which they can emotionally explore together, and begin, within the context of their relationship, to heal the PTSD-suffering partner’s trauma.

Since MDMA was made illegal, its therapeutic potential, the “baby” of Sessa and Nutt’s treatise, has spent years confined to the dancefloor, its potency dimmed by adulterants. By confining the drug to the rave scene and blotting out its medical value, the mainstream media has functioned as a smoke machine, obfuscating the “disco biscuit” in a haze of notoriety and mystery. But, as Katie’s research shows, more and more ravers are stumbling out of the smog and accessing glimmers of MDMA’s stifled healing properties.

Most clubbers’ nightlife careers feature the odd, pivotally important memory of an emotionally-laden, and strenuously gurned, heart-to-heart. But the “baby,” the therapeutic potential of MDMA, has limited applications whilst it remains stuck in the rave scene. The fact that Katie’s couples have had the luck to buy substances that perform like MDMA, and have taken them in the right set and setting to access the drug’s famous therapeutic benefits, show that these properties have not been destroyed, no matter how risky it has become to try to access them. On the contrary, Katie’s findings -and particularly the fact that she sourced most of the couples that provided them from harm-reduction forums- suggest that there is a demand within the recreational community for a safer means of exploring the therapeutic effects of MDMA: the “baby” has been sitting on the side of the dance-floor, teething tetchily on slobbery glow stick, for long enough. Surely it’s time to give it a legally-regulated leg-up into the bathtub?

I’m not positing the MDMA experiences Katie documents as an ideal to pursue: all clinical researchers of psychedelics take great care to distinguish their results from any experiences achieved through recreational drug use. (Think Dr. Robin Carhart-Harris’s qualification, after leading the recent Beckley/Imperial trial of psilocybin as a treatment for depression that, “I wouldn’t want members of the public thinking they can treat their own depressions by picking their own magic mushrooms. That kind of approach could be risky.”)

But while Katie’s findings may not be ideal (from a risk-perspective), the research she is doing- bringing qualitative data about the positive experiences that can and do result from the recreational use of MDMA into the academic and social discourse- is vital. She is documenting the fact that a significant proportion of the population are currently seeking out these MDMA experiences regardless of its Class A status and corresponding dangers.

Research like Katie’s makes it increasingly impossible for politicians to legitimately continue to ignore the non-problematic drug using proportion of the population. It also undermines the prohibitionists when they peddle the idea that MDMA-related deaths are a consequence of MDMA itself, rather than a consequence of the fact that there are no quality controls or instructions to accompany illegally-sold MDMA, and undercuts the oversimplified portrayal of drug use itself as intrinsically bad, incapable of producing effects like the ones Katie records.

If MDMA could be sold officially in the UK, those who want to try it would be able to purchase it from a shop, at standardised purity, with safety and dosage instructions, and could more reliably enjoy the transformative bonding experiences of the “MDMA bubble.” As the country with the biggest appetite for it, this is the future we have to work towards.

Rosalind Stone is the Communications Officer at the Beckley Foundation. She has written for the Londonist and The Stylist. Tweets@RosalindSt0ne