From the start, the newly born Prohibition Unit encountered problems proportionate to its elephantine size. Inexperienced and untrained, the force was particularly open to pulls of bribe, graft, and corruption, fueled by the vast profits of black market liquor. As a result, between 1921 and 1928 nearly one-tenth of the service was dismissed for cause— including bribery, extortion, theft, and falsification of records, among other offenses. Only 41 percent of agents passed a new civil service test introduced in 1927, gutting the bureau at one stroke. New agents who could pass the exam but lacked practical experience were brought on board to replace the dropouts.

The war on alcohol put these inexperienced federal officials— customs officers, Border Patrol agents, Prohibition Bureau officers—in frequent and often violent confrontations with civilians. Poorly trained Prohibition Bureau officials were, according to federal admissions, responsible for approximately 260 deaths in enforcement of the law. The Washington Herald put the number killed at over one thousand, more likely, though not fully accounting for the dry army as a whole. Tellingly, for example, one Border Patrol agent, reputed to be a “stone cold killer,” estimated that between 1924 and 1934 patrol agents alone had killed close to five hundred “contrabandistas,” cross-border liquor smugglers of Mexican origin. Battling liquor violators was not the fledgling patrol’s primary charge, but it nonetheless became centrally involved in its enforcement. El Paso squads secreted themselves at night along the Rio Grande, waiting to ambush smugglers loaded down with large cans of alcohol or bottled liquor.

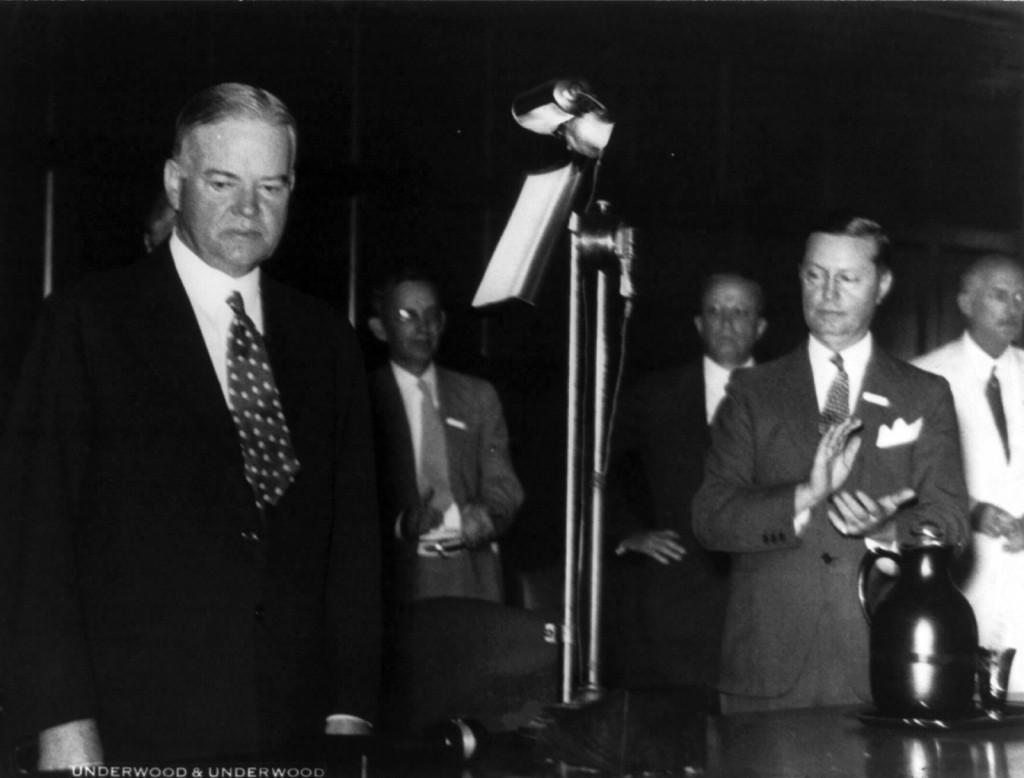

One former agent recalled a gunfight every seventeen days in his subdistrict. Along the border, the war on alcohol provided an opportunity for some of its more notorious gunfighters to engage in the “sport,” as one former agent recalled, of hunting people. Not surprisingly, rife government lawlessness was one of the topics Hoover raised in his inaugural address and a subject investigated by the Wickersham Commission. Killings by Prohibition Bureau agents, compounded by a pattern of acquittal, provided ammunition to the law’s opponents.

President Hoover, however, blamed not the law, but its administration: citizens would obey the law if and when the government established more efficient and professional policing.

The Federal Bureau of Investigation under the nation’s other Hoover was perfectly positioned to profit from the president’s call for more efficient and professional policing and public clamor over crime by building a smaller but more disciplined and respected force than the Prohibition Bureau. J. Edgar Hoover parlayed the public obsession over crime and the all-too-evident problems with the Prohibition Bureau into a brief for his nominally more professional federal anticrime arm. Despite lower funding and congressional attention, Hoover labored throughout the decade to build a law-enforcement agency untainted by the problems that had engulfed the federal Prohibition Bureau. He held his agents to high professional standards, rotating personnel assignments to keep agents from developing corrupting intimacy with local and state politicians. Hoover openly measured the Bureau of Investigation’s professionalism against that of the Prohibition Bureau, and as that agency collapsed his was well placed to fill the void. By 1940, the FBI had doubled in size.

While J. Edgar Hoover laid the foundation for a more professional, bureaucratic national crime-fighting apparatus, Herbert Hoover did not wait to restart a national effort to clamp down on the growing power of organized crime. Frustrated by the thriving liquor traffic, Hoover asked his attorney general, William Mitchell, if he had the authority to call out the military to crack down on rum-running and the violent fights over territory between rival gangs along the Detroit River. The president took a direct role in the effort to capture “Public Enemy No. 1”—Al Capone—soon to be the most famous resident of the federal prison on Alcatraz Island. Hoover charged his attorney general and secretary of the treasury Andrew Mellon with securing Capone’s conviction. Backed by the highest levels of government, the team concocted an unusual strategy. Ignoring the murders committed by his henchmen, for which local and state police failed to prosecute him, it used federal power to convict him of income-tax violations on the unreported profits he made through his illegal businesses. Upon Capone’s conviction, Frank Loesch, the Chicago Crime Commissioner, who also served on the Wickersham Commission, thanked the president for his behind-the-scenes efforts: “I hope that some day you will allow me to tell the public how much you had to do with it and how much impetus was personally given by you.”

President Hoover’s reputation as an individualist belied his use of federal power in the war against crime. He built a more muscular federal prison system. He backed the expansion of the FBI’s purview to include kidnapping in the wake of the Lindbergh baby murder; he called on Congress to widen federal authority to act against criminal gangs engaged in deadly warfare in New York, and he worked to unify, professionalize and expand the Border Patrol, which doubled in size in its first five years of existence. He also bolstered the federal government’s deportation authority “to more fully rid ourselves of criminal aliens.” He won some of that authority when the 1931 Alien Act provided for the deportation of noncitizens convicted of violating antinarcotics law. Hoover’s antidrug chief at the newly born Federal Bureau of Narcotics aided the cause, testifying that “aliens were at the root of the narcotics problem.”

This development points to an underappreciated aspect of the war on alcohol—namely its symbiosis with its less-known twin: the federal campaign for narcotic-drug eradication. The challenge of alcohol Prohibition drew federal officials into more aggressive narcotics enforcement of all kinds, often encouraged by the same reformers behind the Eighteenth Amendment. The nation’s nascent antinarcotics regime was in important ways the stepchild of alcohol Prohibition. It drew upon the dry campaign’s assumptions, logic, infrastructure, and some of its principal actors. There were, however, important differences. Without a tightly organized grassroots movement, the antinarcotics movement was chiefly backed by state agents, moral entrepreneurs, and a small number of influential and well-heeled private contributors such as pharmaceutical companies.

What it lacked in the intense grassroots mobilization for alcohol Prohibition, it gained in the widespread assumption that suppression of recreational drug use constituted a positive public good. Recreational narcotic use was far less popular, identified more centrally as a threat to youth, and its usage was more closely associated than alcohol with marginal, “deviant” groups. As a result, drug prohibition proved less controversial and far outlasted the alcohol Prohibition regime, remaining one of the most significant legacies of the era.

Narcotics prohibition also depended, in a way the war on liquor had not, on international agreements for the suppression of global drug trafficking. The Prohibition Unit’s Division of Foreign Control had successfully negotiated some international agreements to suppress liquor smuggling, but the nation’s nascent antinarcotics regime involved even more centrally a two-pronged strategy of international as well as domestic drug control. While supporters of the 1914 Harrison Narcotics Act had hoped from the beginning to utilize the law as a mechanism to prohibit narcotics use and traffic, the measure passed in the guise of a revenue act, merely requiring anyone dispensing cocaine, opium, and morphine to register, pay a tax, and display a stamp. It did not specifically criminalize nonmedical users of narcotics. Until 1919, the courts refused to go along with federal efforts to use the law to prosecute drug users, interpreting such criminalization as beyond the original intent of Congress. After the ratification of the Eighteenth Amendment in December 1918, however, courts increasingly sided with the prohibitionist goals of narcotics officials. In Webb et al. v. U.S. in 1919, for example, the Supreme Court forbade nonmedical addiction maintenance, a once common practice. Men and women addicted to drugs— previously thought of as morally weak and more pathetic than dangerous—were increasingly classed as criminals.

The logic of alcohol Prohibition, an effort to eradicate the traffic and use of one mind-altering, physically damaging recreational substance, hardened public opinion toward substances widely judged to be more addictive and harmful than liquor.

The passage of the Eighteenth Amendment also sparked new fears that the nation’s tipplers might turn to even more dangerous narcotics. Opponents of the war on alcohol had made that very argument, but once alcohol prohibition became law, that worry led inevitably to a parallel crackdown on narcotic drug use. New York’s special deputy police commissioner in 1920 declared that drugs, not alcohol, were at the heart of the “crime wave,” Prohibition having “driven criminals from whisky to narcotics.” The nation’s fledgling drug-enforcement bureaucracy, created after passage of the Harrison Act, gained significant new power with the coming of alcohol Prohibition, doubling the number of narcotics-enforcement allocations between 1919 and 1920. Antinarcotics enforcement now became a semiautonomous division within the national Prohibition Unit in the Treasury Department, and piggybacked to prominence on the new alcohol enforcement infrastructure.

Congress did its part by passing more expansive drug prohibition legislation, and drug users and traffickers were increasingly put behind bars. Congress established the Federal Narcotics Control Board via the Jones-Miller Act in 1922, outlawing the import and export of opium and other narcotic drugs such as heroin. Heroin had come into circulation to fill a void in the market after the Harrison Act and Jones Miller Act dried up domestic sources of cocaine and opium. Ironically, heroin trafficking increased in no small part due to the suppression of less harmful narcotic substances. The commodity won a favored place in the illicit trade, since it was more potent than opium, with a higher value per weight, and legal manufacture in other countries made supplies plentiful. It also lacked the strong odor of opium and therefore was less likely to be detected by enforcement agents.

The shift of the new illicit traffic toward more potent, dangerous, and thus profitable substances paralleled the illegal liquor market’s turn from beer to harder, more potent liquors that were easier to transport.

This is an excerpt from The War On Alcohol: Prohibition And The Rise Of The American State by Lisa McGirr, published with permission from Norton Publishers and available for purchase in the UK. Copyright © 2016 by Lisa McGirr. Lisa McGirr is a Professor of History at Harvard.

Read Christopher Snowdon’s Volteface review of The War On Alcohol