Drug policy is a complex sphere to navigate for a whole host of reasons. The most important and difficult being that drug use is perceived to be a moral issue.

It is obvious that policies based on morals rather than science are inherently problematic as biases and emotional reasoning cloud our ability to think rationally.

We can argue all day that a moralistic approach to drug policy is wrong, but that on its own will achieve nothing. In order to see positive progress, we need to understand why we can’t agree and how we can change this.

As much as drug use shouldn’t be viewed as a moral issue, it is something that solicits strong gut reactions and intuitive responses.

People tend not to sit idly by when it comes to a discussion on drugs as they invoke strong and polarised opinions from both sides of the political spectrum. Unfortunately, gut reactions lead to irrational thinking patterns from both sides. This is why, despite the evidence that our current drug policies are harmful, scientific studies often fail to persuade the general public.

The speed at which we are seeing global cannabis reform demonstrates that we are making progress but society still has a way to go to destigmatise drugs.

Issues rooted in morality are challenging to unpick and difficult to engage with positively.

Drug reformers are often angry and frustrated with the lack of appetite for policy change. Although this anger is understandable and justified, such a combative and reactive approach does little to introduce change. It also means we are seeing reformers use emotions rather than reason.

Pointing fingers at impractical policies and burying the opposition in evidence does little to change policy, yet it continues to be done.

We must wake up to the reality that the way reform is approached needs to change.

Liberals and conservatives have always disagreed on policies, drug policy being one of many. A key reason for this is a difference in the importance of moral foundations.

Liberal and conservative policy views are manifestations of conflicting views for what a ‘good’ society ought to look like, despite both meaning well.

In his book ‘The Righteous Mind’, Jonathan Haidt heavily discusses moral issues on the political spectrum. As society becomes increasingly polarised, understanding where the left and right differ and why is more important than ever.

Haidt argues there are six moral foundations that explain differing views across the political spectrum. These foundations are as follows:

- Care/Harm: An ingrained attachment to wanting to protect one another, being kind to each other and preventing pain.

- Liberty/Oppression: Feelings of resentment toward those that dominate and restrict our liberties with a common dislike for oppressors.

- Fairness/Cheating: Reciprocal altruism is at the core of justice and autonomy through a shared set of rules.

- Loyalty/Betrayal: Standing with your group and forming shifting coalitions.

- Authority/Subversion: Underlying leadership and followership with a respect for authority and tradition.

- Sanctity/Degradation: Strong repugnance to disgusting and repulsive things

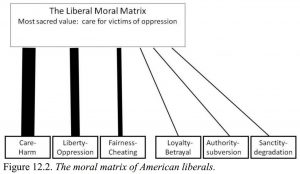

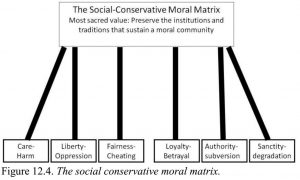

These six foundations guide our moral thinking. Social psychology research demonstrates that the left and right disagree with what moral principles are most important. The figure below shows how important liberals and conservatives find each to be, the thickness of the line shows how important each is rated to be.

It doesn’t take in depth analysis to notice these figures are vastly different. What we see is liberals are primarily bothered about the care-harm principles; they do not want people to be harmed and want policies to prevent pain, which is very relatable to drug reform. The next two principles liberals feel strongly about are liberty and fairness.

On the other hand, conservatives care equally about all moral foundations. What we see is a difference in moral thinking.

This research showcases the inherent difficulty the left and right have for getting along. The entire liberal moral matrix rests on care, liberty and fairness. Whereas, conservatives have a greater number of moral principles to weigh up when considering change. Could it be argued that the right understands moral psychology better than the left?

Liberals often call conservatives out for being afraid of change, novelty and complexity – this isn’t necessarily true, they simply have more to weigh up and consider.

Human nature is oversimplifying complex concepts that fit into a tidy model that involves dichotomous thinking. Truth be told, both the left and right are at fault for such thinking.

Such a simplistic view of ‘good’ and ‘bad’ does little to instigate change when drug policy has a plethora of nuance.

In order for the left and right to ‘get along’ and approach drug policy change positively, we’ve got to understand where we disagree. This will allow us to find a common ground to stand on.

Angry activism, hostility and aggression will not move us forward. Instead, being positive and collaborative will open the pathway for a more balanced approach to change.

At the moment, both sides are shouting with little positive engagement which is driving us further away from a solution.

Current political polarisation for drug policy has led us to believe those on the other side of the spectrum are vastly different to us, when this isn’t necessarily the case.

In order to see positive change, we’ve got to stop seeing the world so black and white – engage with the opposite side, understand their worries and fears in order to bring together all inclusive policy.

This piece was written by Katya Kowalski, Stakeholder Engagement Officer at Volteface. Tweets @KowalskiKatya