A symbol of resistance on the frontline of Thatcher’s Britain, London’s oldest Head shop closed for business after 45 years on New Year’s Eve.

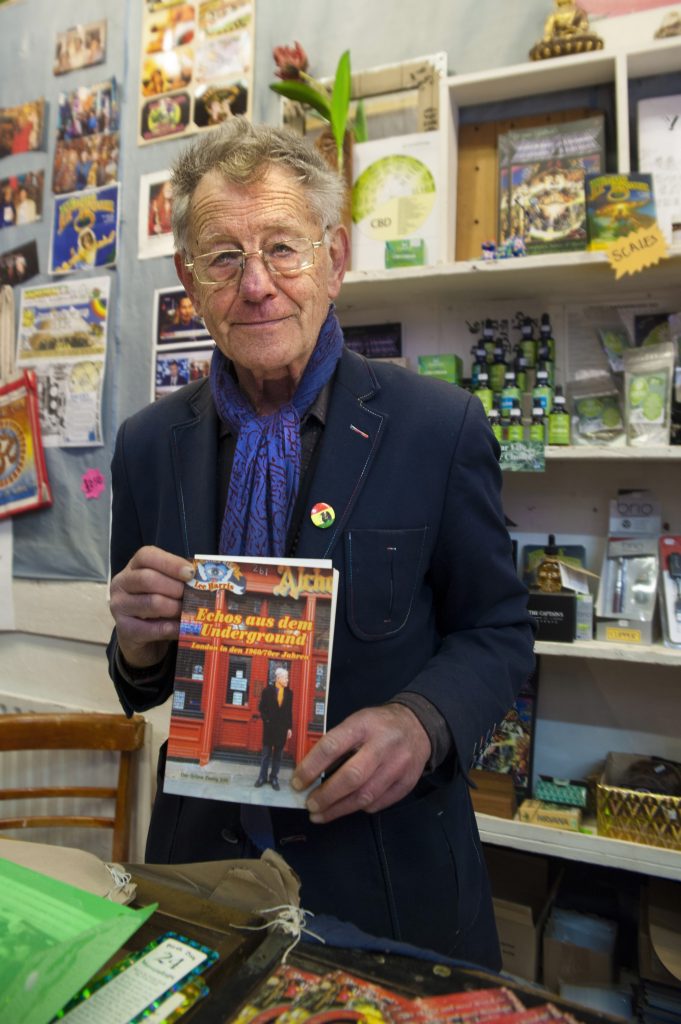

It’s the start of something new for owner Lee Harris, who first launched Alchemy on Portobello Road in 1971.

An artist, activist, playwright, author, healer, herbalist, shaman and publisher – Lee made sure he fulfilled his dreams as he ran the shop to make ends meet.

Alchemy became a stop-off point on the overland hippie trail to Kathmandu – and Lee witnessed the alchemical transformation of Ladbroke Grove as it became a diverse Afro-Caribbean hub for dance hall, Afro-beat, dub-reggae and hip-hop. The roots of London’s Rastafari movement were firmly planted and Lee’s shop became a meeting point for this vibrant community.

“When Rastafarian culture arrived into the Grove, it just brought so much more richness,” he recalls. Symbols of resistance to police persecution like Frank Critchlow became friends with Lee.

“Frank was on the frontline with his famous Mangrove Restaurant on All Saints Road. He was the godfather of black radicalism and targeted by the police. They planted the heroin on him but he fought them and won £50,000. This is how it was, and why Ladbroke Grove was dubbed Viet Grove.”

Fast-forward 45 years, three children and a few grandchildren later: Lee has rolled on with life’s constant changes. Lee’s wife Brigitte, who he met at Alchemy and married in a Buddhist temple, sadly passed away, losing her battle to cancer nine years ago. Gentrification encroached as mansion flats and corporate takeovers forced more and more locals out of the area.

In the meantime, Lee continued to welcome a swarm of colourful regulars to Alchemy, including cult hero Howard Marks aka Mr Nice, Lenny Kravitz, members of Aswad, the Edgar Broughton Band, the Pink Faeries, Shpongle, Hawkwind and Killing Joke. It also became a stop off point for assorted characters like Lynne Franks, brothel madam Cynthia Payne and even the president of Kenya’s son, Oginga Odinga.

“I was playing Lee Scratch Perry on the Wire when he walked in one day,” says Lee. Speaking from his home in Jamaica, Mr Perry recalls: “Punk music wanted to join reggae them days. There were punk reggae parties in Portobello. And many police and thieves chasing the marijuana.”

Perry continues, with a knowing cackle:

“Marijuana is the king of kings, marijuana is the lord of love, marijuana is emperor of emperors, and marijuana is the conquerer of conquerers, and marijuana have a green life span. Green. Life. Span. Water life span! And marijuana is the tree of life, tree of magic, tree of science, marijuana rule and fool all the free mason and the Queen of England, it fool the government, fool all the churches and fool the bishop. The ganja is my life, and my light and my salvation.

We don’t need the Queen of England or no royal family for clear revolution. God give us music to conquer. So we must conquer in the name of music.”

Portobello Road became a hot spot for police arrests of people caught with small bits of cannabis said Lee— a fight Mr Perry continues to condemn:

“Fight against one king ganja and face famine. Yeah man. Love ganja and be free, ganja have immortality to give.”

In 1986, Lee was invited by Lee Perry to join him as he recorded a new track in the studio in Holborn.

Alchemy withstood the storm of change while Lee flew the flag for the legalisation of cannabis. It was from Alchemy he also launched political poster magazine Fara Zine. It was in response to police brutality and racial profiling which saw UK prisons burst at the seams with black inmates – igniting the Brixton riots in 1983.

“Three years later they were still looking to repatriate non-whites, so I got very involved and published Fara Zine with the words of Haile Selassie: ‘until the colour of a man’s skin is no more significant than the colour of his eyes,’ says Lee.

Fara Zine was published just once. It featured the ‘dread poets’ of Portobello and 5000 copies were distributed across London, Chicago, Trinidad and Sydney, and to the likes of Brother Resistance, Sister Netifa and Seko Tafari. Thanks to former Kensington MP Dudley Fishburn, one copy even took pride of place at the Houses of Parliament.

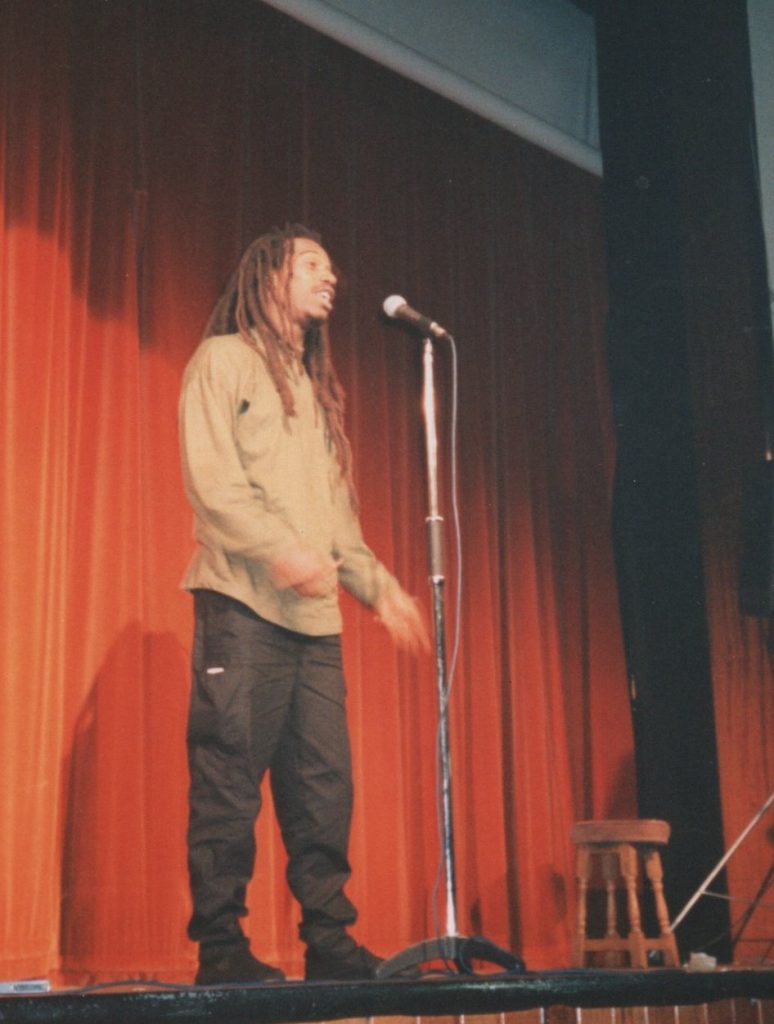

Fara Zine also featured legendary poet Dr Benjamin Zephaniah after he was falsley arrested on suspicion of burglary when trying to report a kidnapping. He said: “I asked them: ‘if I was a burglar, do you really think I’d report a kidnapping at a police station?’

“At the time,” Zephaniah continues, “I remember saying black people don’t even report crime because they risk getting arrested. People such as Colin Roach were dying in police custody in those days, and I know it sounds strange to some people, but I still say today, at least I didn’t die.”

“I remember once I got stopped by the police and they made me pull down my underpants in the road – they really thought I had something but they didn’t find anything. They literally pulled my pants down and exposed me. There was a gang across the road and they almost came towards us to riot, so the police quickly pulled my pants back up and said ‘right, we’re off now.’

He added: “But planting on people was so common in those days – the police would search you and suddenly they’d find something on you. So people like Darcus Howe and the Mangrove Nine and the likes of Linton Kwesi Johnson were real heros. “Linton wrote ‘I stand up in the court like a mighty lion, I stand up in the court like a man of iron, Darcus out of jail.’

“These guys helped form the Black Panther movement so the police really had it in for them, and Darcus was literally on the front line when he was getting locked up and framed.”

Stop and search laws spawned a movement of solidarity across underground Britain as information traveled between frontline areas. “In Birmingham it was Soho Road, in Bristol it was Grovesnor Road, in Leeds it was Chapel Town, in Brixton it was Railton Road and in Ladbroke it was All Saints Road and a stone’s throw away was Alchemy.”

“Sometimes I’d drop by and Lee would ask me what’s happening in Brixton. This was before internet or mobile phones, so we’d go from one frontline to another as a source of information. That’s the way I remember the place.

But in the black community, you had to be suspicious of other white people because you didn’t know if they were informers. So we were very nervous about outsiders, but once they proved they were friends, they were really, really welcome, and Lee was one of those few cool white guys who could be trusted. People would say ‘go talk to Lee, he’ll help you out.’ He was really like one of us.”

Racial discrimination by law enforcement was as synonymous as the war on drugs in eighties Britain and Lee witnessed the brunt felt by the black community through the eyes of Alchemy.

Yet one of the most definitive moments was to still come in 1988. Waiting in the wings was Thatcher’s draconian amendment to the Drug Trafficking Offenders Act.

On Radio 4, David Mellor announced every Head shop would be brought to justice for selling articles to smoke cannabis and use class A drugs.

Lee was the first to be summoned to court. He was sentenced to three months in prison but slipped through the fist of the Iron Lady when he was released on bail two days later. A gruelling 18-month battle ensued.

Huge support for the case was demonstrated by the Alchemy Defence Fund event at the London School of Economics where Benjamin Zephaniah performed alongside comedians Mark Thomas and Arthur Smith.

Then just as Thatcher was on her way out – Lee won his fight against a flawed system in a case that helped save the plight of Head shops across the UK.

“It took me many years to realise it, but I was busted by the police” he recalls. “I remember the day we saw a police van with a drug intelligence cell parked outside. My shop was full of Rastas and outside there was a van full of 20 police officers, all glaring in at us.

I came back to my shop the following week and looked under the shutters to find police photographing people inside so I quickly drove off. My lawyer said ‘be ready to go to prison.’ Before I knew it there was a headline in a local newspaper that read ‘Notting Hill drug squad nabs hubbly bubblies.’

Henk Targowski – who released Mr Perry on his Black Star Liner label – is milling silently behind the counter as Lee recalls the time. Henk walked into Alchemy 30 years ago with a bunch of flyers for a hip-hop night at the Tabernacle and the pair have been best friends ever since.

“I said three things when they tried to send Lee to prison. Firstly – everything here can be used for completely legal purposes.

“Secondly, we are neither trained, nor is it our job to psycho-analyse our customers. And three, I can’t remember the third one now, but at the end of the day, as an anecdote, the Lady Justice has scales in one hand and a sword in the other.”

Lee begins to laugh. “That’s right, and my barrister said ‘where we may see the figure of justice with her scales and sword on top of the old bailey, the police officer may see a drug dealer with an offensive weapon.’

“But after I won my case, the policeman who caused me all this trouble told me, ‘I’m glad you won Mr Harris.’ He wanted to be friends but I just couldn’t, although I do still have his Christmas card.”

News of Alchemy’s recent closure spread like wildfire. It’s just two weeks until New Year’s Eve and a constant stream of visitors fills the shop on this sunny afternoon. There’s an influx of multicultural college kids and old Rastafarian friends, well-heeled silver-haired artistes of lore, city boys, random legends and the odd celebrity. It’s an emotional time for a community of people from far and wide.

Lee is beaming excitedly from behind the counter. Drum n’ Bass blares away as he banters with each person like a long lost friend.

“I met my friend Egbert, a Rasta elder the other day, and he said ‘don’t leave, I’ll miss you,’ – and then he started to cry and we hugged.

“Alchemy has been a meeting place for brothers and sisters. The spirit and warmth of my Rastafarian brethren has been so uplifting. I give thanks to Jah Almighty for being enriched by the Rasta culture and thank the good brethren for their love and friendship.”

Lee’s eyes light up as his close friend, Killing Joke bass player and music producer Martin Youth Glover walks in. Alchemy is full of surprises like this – you just never know who you’ll meet. “It’s the last autonomous zone left – from the legacy of Frestonia and the free squats of the seventies,” he says.

“And now that legacy’s coming to an end. It’ll be the last corporatisation of the free world in this fair corner, but nevertheless, Lee’s done his time, he’s done a great job and been a great friend and mentor to many people. It’s very sad to see it close, but I’m happy he’s going to have more of a chilled out life. The shop has always been about marijuana, and he’s been a big pioneer of the reform of drug laws – and I go along with the idea that when it is legalised, it will end most of our problems.”

The shop is getting quite busy now and as Lee looks up, once again his eyes dance with excitement. Parked up in his wheelchair at the counter is none other than author and inventor of the veggie burger, Gregory Sams. “I knew Lee before he even opened the shop, back when he was selling the International Times on the street.

“Everything changes, and he’s left behind a legacy. He doesn’t need to be here all the time selling cigarette papers – he’s still part of the community, but I will miss coming here to see him.”

It was from Alchemy that Lee also launched Europe’s first magazine dedicated to cannabis. Homegrown paid tribute to counterculture revolutionaries like Alan Ginsberg, Jack Kerouac and Brian Barritt. It was the first to publish the story about Project MKUltra – CIA’s mind control program, and it featured literary works by writers like Peter Stafford and Michael Hollingshead.

Lee achieved his biggest feat ever at the age of 80 last year though when he was chosen to lead the Cannabis is Safer than Alcohol Party in the London Mayoral Elections. “I would have closed the shop last year, but I needed an address in London to stand for the London Mayor,” he says.

As a result, he won over 80,000 votes from Londoners who agreed taxing marijuana would take crime off the streets and bring over £200million in taxes to the city.

Lee was one of eleven candidates alongside contenders from parties like BNP, Britain First and UKIP. “I met them all but learnt from Jeremy Corbyn – ‘do not abuse your opponents’.

“It was a remarkable feat but also one of my lowest moments because I felt we’d been to all this trouble and I wasn’t going to win.”

Lee himself had risen from the ashes of South Africa’s apartheid system where he learnt the art of protest and helped fight racist white laws. His meeting with Nelson Mandela in June 1955 was not in vain, so by the time he rocked up to London the following year, he immediately resonated with the spirit of the beat generation.

But as Lee hit the sordid scene of underground Soho, wide-eyed mods high on amphetamines were a shock to the system. He became a ‘moral crusader’ and a stringer for the Evening Standard journalist Anne Sharpley who’s front page article about Soho’s ‘Pep Pill Craze’ blew the scene right open.

“I didn’t quite understand the impact of what I had done. It was only when I opened Alchemy in 1971 – the same year as the Misuse of Drugs Act – that I thought, ‘Oh God, what have I done?’ because I had helped bring forth a law which had rebounded on my friends.

The police were using racial profiling to stop and search my black friends for drugs and this is when I really understood that prohibition does not work, and when I realised I wanted to undo the damage.”

Lee has certainly left behind a lasting legacy. Alchemy’s closing party at Portobello Mau Mau Bar last month was proof as live music, poetry and performance packed out the place.

Surrounded by local legends and luminaries, friends old and new, it was a bitter-sweet symphony binding a vociferous community that has stood with conviction through one of the most brutal times in modern British history – and broke on through to the other side. Respect and solidarity brought together the Alchemy community and it was a vibe that could be felt at Mau Mau that night.

It marked the beginning of a new chapter for Lee Harris. And at the age of 80, with an album launch, autobiography, exhibitions, performances and events planned for the year ahead – there’s no stopping him yet.

Gentrified warts and all, Ladbroke Grove will continue to change. Portobello Road will never be quite the same – but as Lee says, “It’s the end of an era – but the spirit survives.”

Words by Anu Shukla