Follow the money. In politics, money can tell you more than opinion polls or prime ministerial speeches or newspaper columns. And beneath the skin of the drugs debate, the money is saying something interesting.

On the surface, it seems hopeless. Home secretary Theresa May recently steered the jaw-droppingly draconian Psychoactive Substances Bill through parliament. The Lib Dems, who provided a bastion of liberal thought on the issue, have been exiled into the political wilderness, possibly never to return. Even Jeremy Corbyn, who seems to have time for every crackpot theory brought to his door, doesn’t want to go near it. The drugs debate looks dead in the water.

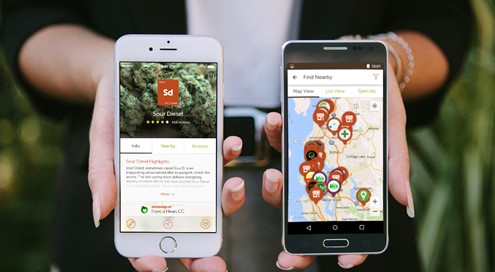

But below the surface, the money is moving. Brendan Kennedy is the CEO of Privateer Holdings, an innocuous sounding name for a seriously interesting company. It encompasses three cannabis brands: Leafly, an information resource about strains; Tilray, which produces medicinal cannabis; and Marley Natural, which produces cannabis for recreational users. It operates strongly in places like Canada or Colorado, where progressive government policy has opened up a space for a cannabis market. But Kennedy is seeing lots of UK investors take interest too.

I meet him in a Starbucks on Baker Street, in between meetings. “We have a lot of investors from the UK, a lot of investors from London,” he says. “Probably somewhere close to 20.”

Business is going well, given people are putting their money into an industry which either doesn’t exist or resides in a regulatory grey area subject to political change at any time. “We raised $7 million in our first round, $75 million in the second round and I think we’ll raise an additional $100 million this year,” he says. “It’s mostly from high net worth individuals and institutional investors. There is a sense of the inevitability of cannabis becoming legal. There’s a fear of missing out on an investment opportunity. So they look for potential targets for investment and they end up with us. I don’t make that statement out of ego. There just aren’t a lot of opportunities.”

The American businessman is a strange figurehead for a drug reform movement usually associated with political bloggers and bearded activists. He’s suited, handsome, optimistic and unmistakably corporate. This guy isn’t in it for the politics. He’s in it for the money. And that makes him a useful barometer of investor thinking about cannabis reform.

In May 2010, he was sitting in his office at a venture capital bank in San Francisco when a medical cannabis tech firm paid him a visit. He’d not really been in contact with cannabis much before that, aside from the standard university encounters you’d expect of someone growing up in California. But by the end of the meeting he’d decided that this could be the moment to get in on the ground floor of an embryonic cannabis industry.

“It was this wide open space,” he says. “Exactly the kind of opportunity I was looking for. Something that was immense and inevitable.”

For a year he went on a sort of marijuana world tour: Colorado, Oregon, Washington, Canada, Israel, Jamaica, Spain and the Netherlands. He met cultivators, dispensary owners, patients, physicians, pharmacists, lawyers and political activists. “Our fundamental thesis is that this is a mainstream product consumed by mainstream people,” he says, “and, because of that, legalisation is inevitable”.

Kennedy is in the UK on the same week that a Liberal Democrat expert panel published its opinion on how to introduce a cannabis market to the UK. Their approach was motivated by a sense of what was politically possible, rather than commercially desirable. They wanted to arm sympathetic MPs with a conservative, steady-as-she-goes system which could address the concerns of their critics, particularly in the tabloid press.

Under this model, a Cannabis Regulation Agency would oversee production and distribution, through specially licensed pharmacy-like retail outlets. Packaging would be plain and alternative methods of consumption, like edibles or vape-sticks, banned – at least in the short term. Kennedy is on the other end of the spectrum. He’s a businessman. He envisions a liberal market, more akin to the alcohol industry.

“Brands are how you win.”

“Brands are everything,” he says. “I’m in this to wipe out the black market, to wipe out the criminal organisations supplying and distributing cannabis around the world. Brands are how you win. Any consumer will chose a branded product over something in a plastic baggy. Brands inspire confidence and trust. Brands imply legitimacy. They reduce barriers to change. They give comfort to consumers. People are looking for a product which is safe, properly labelled and consistent from experience to experience.”

Across the world, he encounters a spectrum of different regulatory systems, from the relatively laissez faire approach of California to the tight control of Canada, where the company holds a federal licence. “Regulators appear twice a week,” he says, sipping from a bottle of mineral water. “The product is tracked from seed to sale. Our facility is state of the art. It’s like nothing else in the world – part Silicon Valley manufacturing, part pharmaceutical plant, part Nasa space station.”

Their latest permit was for something which alleviates chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting. With products like that, they amp up the cannabidiol level and lower the THC, so that the medicinal effects crowd out the high. They recently received a request for a treatment for childhood epilepsy which would have only a trace amount of THC, at a ratio of 1 THC to 50 CBD. Once you bring the product above board, it’s astonishing how quickly manufacturers can tinker with it to target specific medical conditions.

But the firm still has to abide by restrictive marketing and advertising regulations. They currently have 5,000 patients in Canada, but have suddenly found themselves in a steep growth curve. As things stand, they’re adding 500 patients a month.

It’s not just laws that count

What happened? Politics. The election of new Canadian prime minister Justin Trudeau put rocket boosters under the enterprise. It’s not that the regulations have changed – it’s that regulators are recognising the mood music from government and loosening their top buttons a little. Things are becoming more flexible. This is the murky world Kennedy is operating in. It’s not just laws that count. It’s also the political debate around existing regulations which can define the company’s room for manoeuvre.

Kennedy opens up a company brochure and shows me some of the products being sold under the Marley Natural brand – high grade pipes and rolling boards and the like. The weed itself is sold in attractive baggies with a prominent logo on the front. He flicks the page to show me the vaping products they’d be selling. It looks like a standard e-cigarette, except its 100% cannabis solution – no nicotine whatsoever.

Slick packaging of Marley Natural Products. The Lib Dem expert panel advised against this, recommending ‘pharmaceutical style’ packaging. (Source: Privateer Holdings)

This product reflects the frustrating tug-of-war between reason and politics in the cannabis debate. On the one hand, it is a literal life-saver. The vape pens could once and for all cut the link between cannabis and tobacco. But on the other hand, vaping pens make it harder to argue that legalisation will not result in an increase in the number of people experimenting with cannabis. They are attractive and seemingly harmless. One could easily imagine someone who wouldn’t smoke a joint being prepared to give them a go.

That’s why the Lib Dem expert panel advised against legalising cannabis vape sticks, despite their health benefits: it would make it harder for a politician to say legalisation would not result in an increase in cannabis use. But for Kennedy, that would be an insane move: the vape sticks are a good product, and they’ll save lives.

These are the kinds of frustrating debates cannabis reformers need to have as legalisation continues to spread throughout the world. And they need to do it fast, because things are moving quickly. Germany recently voted in a bill creating a national medicinal cannabis programme providing even for insurance company coverage. The Italian Air Force is producing medical cannabis on a base outside Milan. Kennedy’s Canadian plant is shipping product to the Czech Republic, Croatia and Finland. Even a university in Dublin, which is hardly famous for its liberal approach to anything, is participating in clinical trials on cannabis which would be unimaginable in the UK.

“You have a conservative press which is 40 years out of date”

Britain, however, lags behind. “It’s different here,” Kennedy says. “It’s frankly different to anywhere in the world. In the other Commonwealth countries – Australia, Canada, Jamaica – things are moving on. But there’s not even a conversation in the UK. You have a conservative press which is 40 years out of date in terms of understanding of this particular issue. And there isn’t the patient activist base we’ve seen in other countries. You’ve a lot of politicians who say medical cannabis should be available but aren’t willing to spend the political capital to take action on that statement.”

Vaping. Unquestionably safer than smoking tobacco, but also opening the door to increased cannabis use? (Source: Flickr – Vaping360)

That might not change. Just because British investors are prepared to put their money into a cannabis company operating overseas doesn’t mean we’ll be seeing political change at home anytime soon. But Kennedy is convinced that the international reports of medical improvement will spark a new popular demand for political change in the UK.

“It’ll change when patients in the UK suffering from half a dozen very specific medial conditions see that patients with the same ailment in Germany or Italy have access to something which is alleviating their conditions,” he says.

The debates we hear about sufferers being refused access to expensive drugs by NICE, the body which grants NHS licences, could soon turn into a patient-led demand for access to medicinal cannabis. That might just provide the impetus to a successful cannabis legalisation movement in the UK.

That’s the long-term dream, anyway, for investors and campaigners alike. Surveying the political landscape in the UK, it seems terribly remote. But money doesn’t lie. Those investors meeting with Kennedy are a sign that key businesspeople are seeing which way the wind is blowing. And it provides a more optimistic picture than Westminster would have us believe.

Ian Dunt is the editor of politics.co.uk, political editor of the Erotic Review, and appears regularly on radio and TV. Tweets @IanDunt