She is extraordinary, there’s no doubt about that. Amanda Feilding, the artist and campaigner also known as the Countess of Wemyss and March sits in a gorgeous flat overlooking the Thames at Chelsea and tells jaw-dropping stories about her life as an aristocratic rebel in the Sixties and Seventies – like the time she drilled a hole in her own head, to elevate her consciousness.

“I remember saying that it felt like the tide coming in. I certainly felt a silence in my own head,” says this beautifully-spoken 73-year-old who can appear eccentric in the extreme.

Back in 1970 she wrapped a bandage around her head and wore sunglasses to stop the blood getting in her eyes when she used an electric drill to pierce the bone, upstairs in this flat, with a camera rolling. There was a bird in the room she had rescued as a chick and with whom she experienced a telepathic bond that lasted years. “We were lovers.”

It’s hard to know what to say to that – but on the other hand, it would be a huge mistake to dismiss Amanda Feilding because of her eccentricity. She drilled that hole because she is a pioneer, an adventurer, one of those who dare to experiment no matter what the risks to themselves.

And she is extraordinary in another – much more remarkable and useful – way too: as a tireless campaigner, fixer, arranger, networker, cajoler, persuader and agitator for the things she believes in, a voice in the wilderness that is now being listened to and vindicated at last.

For half a century, she has been asking scientists, doctors, politicians and anyone else who will listen to accept and take seriously the medical and pyschological benefits of certain drugs including cannabis, magic mushrooms and even LSD, the most demonised substance of them all.

Her moment has come. We are meeting on an April afternoon before she goes off to the Royal Society in Piccadilly to host the presentation of the results of a ground-breaking study by scientists at Imperial College, London, into the effects of LSD on the brain – part of the Beckley/Imperial Research Programme, which she co-directed with Prof. David Nutt. Stunning images captured by an MRI scanner will show the drug sparking new connections between different regions of the brain that do not usually talk to one another and these are already making headlines around the world.

For the first time, scientists can see potential reasons for the loss of ego that some people feel when they are on LSD and the sense of being at one with the universe. There is the possibility that relatively small, carefully controlled doses of LSD could be used in medicine to break harmful repetitive patterns of thought and treat depression or addiction – as doctors were beginning to believe in the Fifties and Sixties before the drug was banned.

The first human trials with LSD for more than 40 years have come about because of Amanda Feilding, although not many people realise it. The New Scientist has called her The Queen of Consciousness, but generally her efforts remain hidden behind the name of the organisation she set up to fund and run the work, the Beckley Foundation.

It’s named after Beckley Park, a Tudor hunting lodge with three towers and three moats that she owns deep in the Oxfordshire countryside, the ancestral home of her family that can trace its lineage back to Charles II.

“I work fifteen hours a day, seven days a week, but people like to think I swan around in luxury, blah blah blah,” says Feilding with a dismissive smile. “Which, if you do work such long, exhausting hours, is slightly irritating!”

She has always been well connected, whether with the likes of Mick Jagger or members of the aristocracy. The Countess had an office at St George’s House in Windsor Castle until she had to move, because the teenage Prince Harry had been caught smoking cannabis at school. By then she had set up the Foundation with the aim of using the latest neuroscience and technology to investigate the effects of cannabis and psychedelics on the brain – although at first she was told by leading scientists that there was no way they would ever be allowed to experiment with LSD.

She hustled and harried friends and allies into supporting the work financially, recruiting supporters including the billionaire philanthropist George Soros and her own second husband Jamie, who is the 13th Earl of Wemyss. The Foundation published more than 40 books on the science of drugs and drug policy and made a big noise in 2011 when it released a very high profile open letter declaring that the so-called War on Drugs was a failure and the world needed a new approach.

Nine presidents and 14 Nobel Prize winners signed the letter, including Jimmy Carter and Desmond Tutu. Sting, Yoko Ono and Sir Richard Branson also put their names to it. Meanwhile, Feilding had begun a research partnership with Professor David Nutt, who was formerly the government’s drugs tzar. He was sacked as head of the Advisory Panel on the Misuse of Drugs in 2009 after it said alcohol and tobacco were more dangerous to the public health than ecstasy or LSD. Those things were objectively true, but ministers did not want to hear them.

Professor Nutt is now chair of neuropsychopharmacology at Imperial College, which persuaded the authorities to allow a limited trial using small amounts of LSD on 20 men and women in the lab at Cardiff University in 2014. “I think our overturning a 50-year ban on research on LSD and discovering how it works on the brain is one of the great achievements of modern science, as important to neuroscience as the Higgs boson discovery was to particle physics,” says Nutt, making a bold claim.

But the truth is that suddenly, serious medical experts are contemplating what would have been unthinkable before: the use of LSD to treat mental health conditions.

Now there are calls for it to be removed from the Schedule 1 list of banned drugs so that full medical trials can take place.

“I hope this research will launch a wave of new research and recognition of LSD as the jewel in the crown of psychoactive substances,” says Feilding.

Volunteers in this trial were given either a small dose of LSD or a placebo and asked to describe their reactions during and after MRI scans. “I did not know where I ended and my surroundings began,” said one volunteer. Another was fearful, though. “Where’s the line between putting yourself on the petri dish and suddenly going, ‘No, hang on, I’m going to destroy myself’?”

It’s a fair question, and the reason we started with a description of how Amanda Feilding drilled a hole in her own head. To understand her, you have to know she has been fearless in her experiments with her own body and mind over the years, starting by using herself as a laboratory for LSD in the Sixties and Seventies.

“It wasn’t flower power. It wasn’t dancing around having a lovely time and laying back listening to music, you know.” She says in a room with an elevated deck that could have been designed exactly for that purpose: strewn with richly coloured Indian cushions, it has a view across the water to the Buddhist peace pagoda on the other side.

She insists on the poverty of her childhood, although she was able to buy Beckley Park, her childhood home, when her parents died and it came up for sale, and has lived in this flat since 1965. “I grew up in a fairly odd circumstances which was total isolation up a very bumpy track on the edge of the moor in a house surrounded by three moats, with no money so there was no heating, or neighbours or luxuries like that,” she says.

“My father was very anti-establishment and a charming, lovely person, but not of the outside world. And didn’t really respect it much. I remember him saying: ‘Whatever the government tells you, always do the opposite’.”

At the age of 16 she ran away from the nuns who tried to educate her. “I won the school science prize and I wanted books on Buddhism and mysticism but the nuns wouldn’t give them to me, so I said, ‘Thanks very much, I’m leaving.’ I went off with £50 in my pocket to see my Buddhist godfather in Ceylon, but never got there. I got to Syria and lived with the Bedouins instead.”

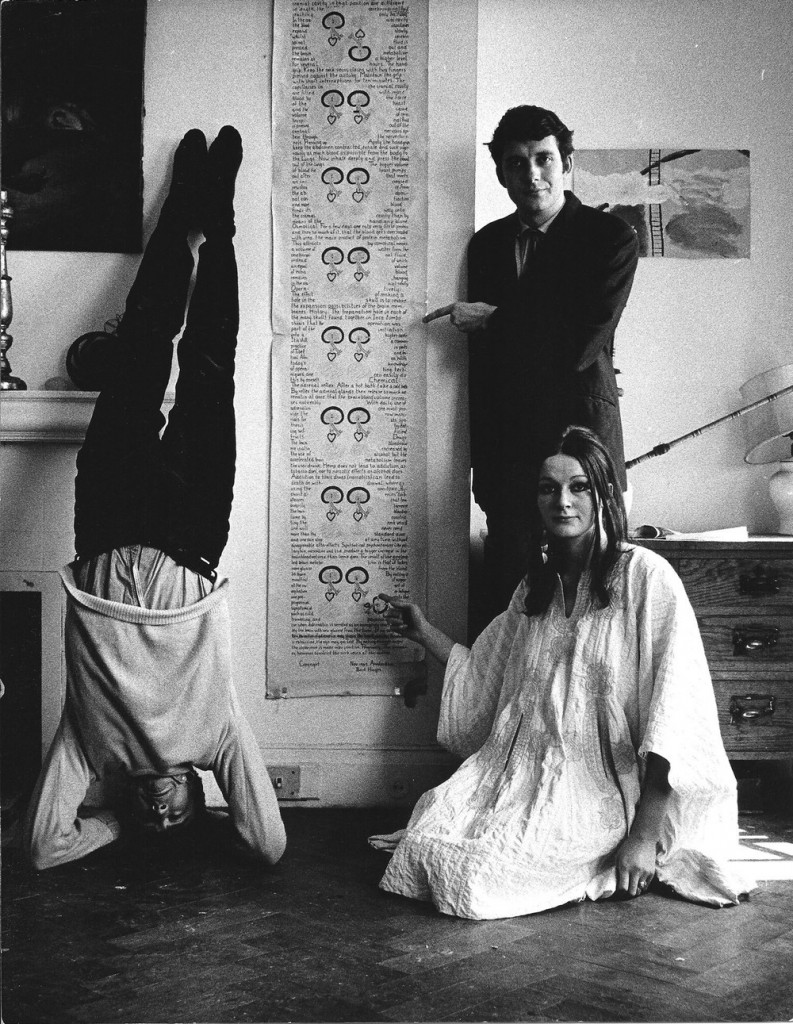

Then in 1966 she met the Dutch scientist Dr Bart Huges and began working with him as well as becoming his lover. “We were working on how the physiology of the brain changes with taking psychedelics, how this could be useful, what has happened to Man, why is he such a neurotic animal. The hypothesis was that he lost a volume of blood from the brain when he first stood upright, and to compensate he developed this mechanism of repression which became the ego. That makes us the incredibly brilliant animal we are, but the flipside is the repression and the loss of contact with reality.”

A part of his theory was that trepanation – or drilling a hole in the skull – would allow more blood in the brain capillaries and thereby lessening the need for repression. “It took me four years to decide to go ahead. I tried to find a doctor who would do it, but something always happened to stop them at the last minute.”

So in 1970 she did it herself and filmed the whole thing. Was she not scared? “I am an incredibly cautious, paranoid, fearful person … but I am a sculptor, I can make a hole in my head. I used a flat-bottomed drill.”

Oh, that’s okay then.

“The trouble with trepanning is that it sounds mad, but there’s a serious hypothesis underlying how it improves cerebral circulation, which I have been researching with a leading Russian neuroscientist.”

She still believes in it, though, and hired a Mexican surgeon in 2000 to repeat the procedure for her. Jamie has also had a hole drilled, but she is wary of talking about it any more. “I’d prefer not to muddle it with LSD research because, I mean, LSD is bad enough …”

In other people’s eyes, she means. The link is that she saw them both as a way of bypassing the ego. “It is totally amazing, knowing what a potentially benign substance LSD is,” she insists. “It’s non-toxic and it is very dose sensitive, so there is no need to use it in the doses of the Sixties, which were usually 250 micrograms.”

That’s more than three times what the Imperial College volunteers were given. “It can be used in small doses to add sparkle to awareness, consciousness. So it’s very hard to see why it has this horrific taboo around it.”

Actually, it’s not. Lysergic acid diethylamide was first made by Albert Hofmann in Switzerland in 1938, synthesized from the fungus ergot, although he said it became his “problem child”. It is one of the most powerful psychoactive substances ever made.

As you would expect, the Countess subscribes to the theory that the American establishment went after LSD partly as it became a symbol of the anti-Vietnam war movement and the counterculture. Then again, military experiments with LSD as a weapon of mind control went badly wrong. But isn’t there a simpler reason why it was banned? LSD is dangerous. People lost their minds. The bad trip was not a myth.

“I don’t disagree. I had an occasion when someone who wanted to take advantage of me put 1000 trips in my coffee. And actually I had hepatitis at the time, so it was the worst trip imaginable. So I know bad trips and I don’t deny their existence.” She won’t describe what happened any further, preferring to put LSD in the best possible light. “I realise the immense value of… using… it… positively. I think it’s an incredibly valuable compound.”

The acid casualties of the Sixties were victims of high doses, she says. “That is something that sadly, occasionally happened and certain people did flip out. They lost the grip of their ego, basically. That was a very sad phenomenon.”

She believes the way to avoid trouble is to take vitamin C first and keep your blood sugar level normal by eating throughout the trip. This has strange echoes of her childhood. “My father was very diabetic, that was a very important thing in my life. I was the youngest. And my job was looking after him. I was continuously feeding him sugar.” She had to feed him? “Yes, he was always passing out. He was terrified of going blind. He kept his sugar level very low, so he was always on the cusp of hypoglycaemia.” So she regulated him? “Yeah.” What would Freud say about that, given the work she has done all these years? “Yes. Exactly.” She smiles.

I tell her that I’ve never taken LSD because I am frightened of losing my mind. “The secret to counterbalance that fear is realising that the amazing thing about LSD is how dose sensitive it is. And you know you can take 15 micrograms and just notice a little bit of a lift. A little sparkle, yeah? I mean if you go to a museum, you see more beauty. Your senses are expanded and integrated so you feel music, you feel beauty. You know, it’s a deeper experience. LSD is a very clean, external, way of doing that and you can learn to manage it. For all you know I could be on it now, do you see what I mean? I’m not but you know, one could be.”

Does she still take LSD? “That’s a question one’s not allowed to answer, isn’t it?”

Particularly if one is about to fly to the United States. We are meeting just before she goes to New York to take part in the United Nations General Assembly Special Session on drugs. Attitudes are changing. The authorities are reconsidering their attitudes to LSD trials. The Beckley Foundation has attracted new sponsorship and she now has a team of eager young researchers. They are already taking the work into the mainstream.

“I could give up now,” she says, “but I’m a compulsive and I love the work and who else will do the research? I know where to look actually in these things because I know how to guide the research and what to look for, as I am familiar with the experience of altered states of consciousness. No one ever thinks I direct research because I don’t have letters after my name, but it’s not the letters that matter.”

The Countess of Wemyss surrounds herself with the best scientists she can find, but for the last half century this extraordinary woman has also been putting her own body, mind, money and reputation on the line in an attempt to prove what she so passionately believes. Eccentric or not, her experience counts.

“It’s what you know,” she says. “That’s the important thing.”

Cole Moreton is an author, journalist and broadcaster. He was executive editor of the Independent on Sunday and chief feature writer for the Sunday Telegraph and was recently named Interviewer of the Year at the Press Awards 2016. Tweets @ColeMoreton