Shadow Home Secretary Dianne Abbott appeared on Nick Ferrari’s LBC Radio show on Tuesday determined to talk about a major plank of Labour’s 2017 General Election manifesto – policing. Specifically, the plan to increase the number of police in England and Wales by 10,000 over 5 years, paid for by reversing cuts to capital gains tax promised by the Conservatives in 2016.

Unfortunately for her, and for her colleagues, it’s safe to say she got herself into a bit of a mess. Asked for specific details on the plan, such as the overall cost, she umm-ed, ah-ed, stuttered, and stammered her way towards an answer that made little sense, and must have seemed like the ultimate gift to the Tories who gleefully pounced, predictably ignoring the multiple other interviews Abbott had given that day in which she’d managed to answer the same question coherently.

If “strong and stable” is the meme du jour of this election, Abbott’s gaffe could hardly have been more perfect for the Conservative spin machine had it been written by Lynton Crosby himself.

Diane Abbott MP

Behind all of the mocking headlines and tweets, however, lies a serious issue. Tory MPs may claim that police funding has been protected by their government – and indeed it has, since 2015 – but during the five years that the coalition government were in power between 2010 and 2015, the police force in England and Wales suffered severe cuts as part of then-Conservative Prime Minister David Cameron’s austerity drive.

Since 2010, police funding has been hit with a real terms cut of around 18%, leading to the loss of around 17,000 officers (or 12% of the force from across England and Wales). In addition, 15,877 support staff and 4,587 PCSO’s also lost their jobs. Specialist units across the country have been forced to disband as massive savings were needed, as explained by Neil Woods, ex-undercover officer and chairman of LEAP UK:

“In many cases, specialist units – units that focussed on child abuse, for example – were scrapped entirely, which should have been unthinkable, but these were the sorts of decisions that had to be made due to the cuts.”

It wasn’t just the specialist units that suffered either. Everyday policing did too.

“Officers were told to cut down on the number of home visits they made in order to save money.” Neil continues, “So when people reported a crime, they weren’t necessarily seeing an officer, as they would expect. This led to a definite worsening of the relationship between police and communities.

“In addition, the officers who were left after the cuts were left with an increased workload. In some places police numbers dropped to lower than what had previously been deemed the minimum required for public safety. Morale suffered enormously.”

Clearly then, despite funding now being ‘protected,’ deep cuts had already arguably made the job of policing more difficult and more dangerous for those officers still in a job.

In which case, surely Abbott and Corbyn’s plan to train more officers to fill the gaps left by those cuts is a good one? Their supporters are certainly at pains to tell you that it is an example of Labour’s desire to reverse austerity cuts, and to get the police force back on its feet. Increase funding for officer training, they say, and the UK will be a safer place for all.

It’s an appealing argument, and one that seems at first glance to based on sound logic. More police equals less crime; who could argue with that? It just makes sense. Indeed, when then-Home Secretary Theresa May announced cuts to the policing budget back in 2010, the Police Federation of England and Wales produced a highly emotive poster campaign warning that lives would be put at risk by reduced numbers of officers.

Despite how tempting as it is to go along with the argument that less police equals more crime, and that therefore increasing police numbers by 10,000 will necessarily lead to a reduction in crime, the numbers don’t add up. As Woods points out, “Cuts didn’t cause an increase in crime, so it could be argued that despite the downsides, they were justified.”

Indeed, despite the huge cuts, police numbers are still relatively high. The massive increases in spending during the Labour government between 1997 and 2005 mean than when it comes to simple numbers, there are about the same number of officers now as there were between 2000 and 2003.

Source: Paul Townsend

Which isn’t to say that increasing funding now would be a bad plan – anything that increases morale in a job with a suicide rate comparable to that of the armed forces is certainly going to be welcome, it’s just that throwing all that money at hiring more officers isn’t necessarily the most effective way of spending it.

In Tom Gash’s excellent book, Criminal: The Truth About Why People Do Bad Things, a whole chapter is dedicated to the ‘myth’ that “We need more bobbies on the beat” in order to reduce crime. The conclusions are startling. Gash describes a series of studies and social experiments undertaken in the US and UK, that seem to turn the logical assumption that more police equals less crime completely on its head.

In one such experiment, which took place in Kansas City in 1972 – in the midst of rising crime rates across the United States – the police force, led by their Chief of Police Clarence Kelley, decided to test the effectiveness of patrols. To do so, Gash explains, they had to “effectively ‘switch off’ patrols entirely in five of Kansas City’s fifteen beat areas.” In order to make the experiment as scientific as possible (and to waylay obvious fears about an increase in crime across the city) patrols were doubled in five of the other beat areas, and stayed the same in the remaining five.

Many of those involved expected to see better results in the areas that had doubled their patrols, but the conclusion of the report into the experiment (which ended up running for a full year) was shocking:

“Analysis of the data gathered revealed that the three areas [one with no patrols, one with historic levels of patrolling, and one with doubled patrols] experienced no significant differences in the level of crime, citizens’ attitudes toward police services, citizens’ fear of crime, police response time, or citizens’ satisfaction with police response time.”

As Gash puts it in his book, “Random patrols in marked cars, which had been absorbing a vast chunk of the department’s budget, simply didn’t work.”

There are many other stories similar to this in Criminal which touch on issues such as the reporting of crime – the same Kansas City experiment found that the average time taken for a crime like assault, robbery, or rape to be reported was 41 minutes, making the focus of many politicians on response times almost completely pointless – to the existence of crime ‘hot-spots,’ which suggest that rather than hiring thousands of extra officers, we might be better served by simply placing them in areas where we know crime is a particular issue. After all, the majority of crime is opportunistic in nature, and according to a Home Office report from 1984, the average police officer walking the beat is likely to come across an active burglary only once every 8 years.

The hot-spot issue is particularly relevant in the UK today, as fears continue to rise about an apparent spike in knife crime in the nation’s capital. This increase in crime has been used by some to help justify Labour’s plans for 10,000 new officers, but in reality extra police presence in high-crime areas of London would probably be just as effective. Besides which, despite the slight rise, the number of knife crimes reported last year is still almost 20,000 fewer than in 2004.

Despite the plethora of compelling arguments put forward in Gash’s book, however, there is one area on which he didn’t touch: the policing of our drug laws. Given the well-documented and hugely negative effect that the criminalisation of drug users has had on the relationship between the police and their communities, not to mention the police’s ability to do their job properly, this is perhaps a surprise.

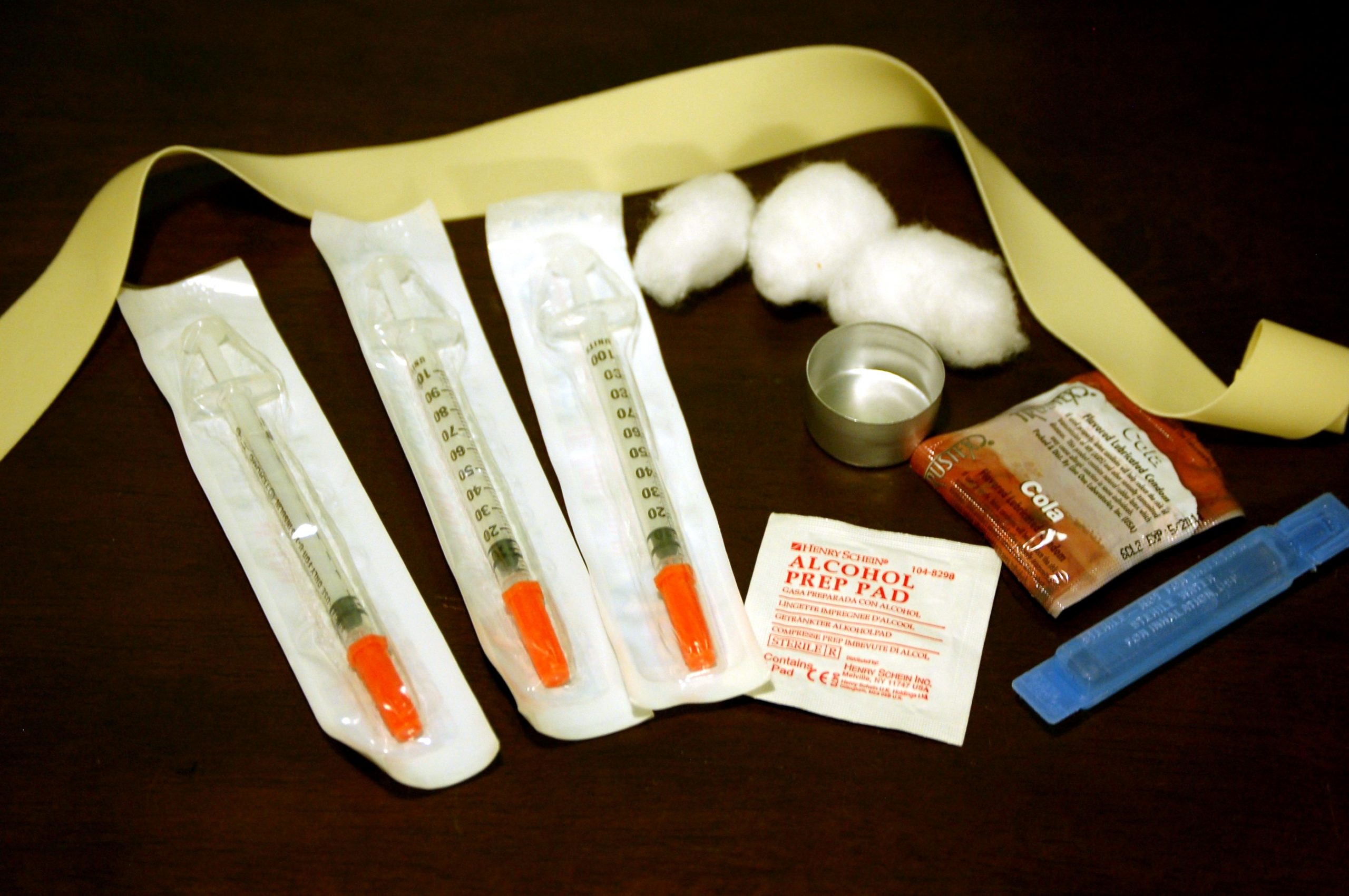

I would argue that, far from spending money on 10,000 new officers, Labour (and all the other parties) would be better served by taking at least some of the £800 million that that would cost and spending it on policies that are actually proven to reduce crime. Take Supervised Injection Facilities (SIFs) – evidence from around the world has shown time and time again that providing injecting drug users with a safe space to inject their drugs not only reduces the visibility of drug use, it actually lowers use itself. Which is to say nothing of the fact that it saves lives. There has never been an overdose death in an SIF anywhere in the world.

Equally, Heroin-Assisted Treatment is proven to reduce overdose deaths dramatically, and providing users with regulated doses of heroin – as we used to do in the UK – is by the far the most effective way of helping users to quit or control their use. Needle exchanges and Naloxone provision, like the other tactics mentioned, are life-savers, and cost far less money to implement than the hiring of 10,000 new police officers.

But most importantly perhaps is the knock on effect that implementing these services would have on crime. According to a 2013 Freedom of Information Request, Home Office figures suggest that “between a third and a half of all acquisitive crime is committed by offenders who use heroin, cocaine or crack cocaine.” It follows then, that reducing the use of Class A drugs, or ensuring that users do not have to commit acquisitive crime in order to fund their drug use, would save the police vast amounts of time and money.

And we know that it works. For decades, a small surgery in the Wirral prescribed heroin to up to 400 of Liverpool’s heroin users. During that time, Inspector Michael Lofts studied 142 heroin and cocaine addicts in the area, and found there was a 93% drop in theft and burglary. In addition, the number of heroin users in the area fell and, as Inspector Lofts told a newspaper at the time, “Since the clinics opened, the street heroin dealer has slowly but surely abandoned the streets of Warrington and Widnes.”

Now imagine that on a national scale. The social and economic cost of Class A drug use in England was estimated by the Home Office in 2003/04 at £15.4 billion. Implementing relatively low-cost methods which have been proven to drastically reduce that cost, whilst simultaneously reducing acquisitive crime dramatically, should be a no-brainer. It’s certainly a far more sensible option than spending another £800 million on extra police officers who, according to the evidence already presented here, may not make any difference to crime rates at all.

Having said all that, these harm reduction policies – as vital as they are – should take place within a much larger process of regulation of the UK’s drug markets. Doing so would not only dramatically decrease crime, it would also free up vast swathes of police time and resources, and would be a huge step in repairing the damage done to the relationship between the police and the people which has been all but destroyed by decades of punitive drug policy and now police budget cuts. If Labour, or the Tories, or the Lib Dems, or any other party is serious about reducing levels of crime and making the country safer for everyone (including drug users), then this step should be indispensable.

The problem of course, is that none of the major political parties are likely to listen to the evidence, instead preferring to stick to over-simplistic rhetoric that plays on constituents fears of rising crime, drug-addicted ‘zombies,’ and the urgent need for massively increased police presence on our streets. Dianne Abbott’s gaffe on Tuesday was that she forgot some numbers, but the much larger gaffe is being committed by politicians from all points on the political spectrum – they simply don’t know or understand the numbers, and they don’t want to.

Deej Sullivan is a journalist and campaigner. He is a regular columnist for Volteface, writes on drug policy for politics.co.uk, London Real and many others, and is the Policy & Communications officer at LEAP UK. Tweets @sullivandeej