Could illicit drugs transform from being a source of violence into a source of political order?

To many law enforcers, the question is completely heretical. For how could a criminal enterprise – associated with violence in so many countries across the world such as Colombia, Mexico, Afghanistan, Myanmar, or Mali – ever bring about stability? The business of illicit drugs, many say, is simply a predatory and corrupt cause of violence and disorder. To even insinuate otherwise is sacrilegious.

The evidence emerging from the experience of some countries, however, says otherwise. Rather than dismiss such evidence as heresy, policy-makers would become better informed if they could carefully look at and consider what may really be going on.

In 2009, two US-based professors of political science – Richard Snyder and Angelica Duran-Martinez – confirmed that something was amiss in the historical understanding of opium and heroin production in the conflict-affected mountainous areas of north-eastern Myanmar.

Before 1989, there were some 25 insurgent ethnic armies operating in remote regions of the country, many of them operative since the 1960s. Around eight – who also happened to be the largest armies – operated in the Shan and Kachin regions of the northeast. As the conflicts dragged on year by year, most if not all started turning to opium cultivation and trafficking to finance their armed struggles. In this sense, illicit drugs came to be seen as a direct cause of violence and instability.

What is curious, however, observed Snyder and Duran-Martinez, is that following the dramatic increase in opium and heroin production after 1989, the biggest of these opium-financed rebel armies did not expand. They did not engage the Burmese military in more battles, and neither did they extend the scope of their campaigns, nor widened their bases of operation. Instead, they demobilised. Consequently, there was a dramatic reduction in the levels of violence.

By 1997, 23 insurgent groups had made peace with the government through formal ceasefire agreements that allowed them to keep their bases, arsenals, and sources of funding.

By then, opium and heroin had become Myanmar’s largest export, “pumping more than half-a-billion dollars annually into the economy, an amount exceeding the government’s official tax revenues”. When elections were held in 2010 and new national and state legislatures were convened, eight politicians from Shan State identified as ‘drug lords’ were elected – the legitimate choice of voters from opium poppy growing regions. In this sense, opium had arguably become a source of stability.

The international community was not unaware of what was going on. For successive years from the mid-1990s to early 2000s, the annual International Narcotics Strategy Control Report (INSCR), published by the US Department of State, had been stating that as a means of maintaining peace and apparent stability in Myanmar, “criminal elements were not only permitted to engage in illegal activity but also encouraged to invest ill-gotten gains into legitimate commercial development”.

An Italian academic and NGO officer, Filippo de Danieli, found similar patterns in Tajikistan where heroin, he argues, had become a basis for stability as well. De Danieli showed how Tajik drug ‘mafias’ effectively helped preserve order after the 1997 peace agreement that ended the civil war. The mafias either eliminated potential threats, such as smaller insurgent groups or ‘spoilers’ unwilling to abide by the peace agreement, or were mobilised to actively settle disputes in the most unruly areas that the cash-strapped and ill-equipped central government could barely reach. In return, the state ‘allowed’ them to continue their drugs business.

Of course, some of those eliminated were small competitors to the oligopoly of 20-30 groups in the drugs trade that became dominant after 1997. But the key point, De Danieli emphasizes, is that it is not the commodity itself – opium or heroin – which is the source of stability or instability. Rather, it is the reciprocal arrangements for mutual benefit that ultimately generate order or disorder.

[READ] ‘Secrecy for Sale’ – Eric Gutierrez on The Panama Papers, and the Illegal Drug Trade

Illegality does not automatically breed violence, contends Snyder and Duran-Martinez, especially when authorities become successful in constructing a ‘state-sponsored protection racket’. They defined this racket as “informal institutions through which public officials refrain from enforcing the law, or alternatively, enforce it selectively against the rivals of a criminal organisation, in exchange for a share of the profits generated by the organisation”.

The racket could emerge only under certain conditions. First, state officials must have a credible capacity to enforce the law. Because without a credible threat of enforcement, why would criminals pay for non-enforcement? Thus the stronger the illicit actors, the stronger and more capable the state must be if it is to successfully induce those illicit actors to participate and comply with the terms of the protection racket.

Second, criminal organisations also need to have the capacity to offer a credible guarantee that they will share the spoils, and that they can comply with any agreed on behaviour, like refraining from violence when needed, sharing information, or controlling ‘public hazards’. Thus, in order to be credible partners in a protection racket, “criminal organisations require a certain level of internal command, control, and coherence”.

Because these two conditions were apparently met in Myanmar and Tajikistan, opium transformed from being a source of instability into a source of political order.

The validity of the argument is strengthened by Snyder and Duran-Martinez’s careful comparison of Myanmar’s experience with Mexico. They conclude that it was the breakdown of the state-sponsored protection racket that led to incredibly high levels of violence in Mexico. Because police and state officials in Mexico were constantly rotated or purged, stable deals with criminal organisations became harder to cut. Furthermore, the overlapping jurisdictions of Mexican federal and state authorities made it more difficult for criminal organisations to decide which ‘protector´ to develop relations with.

Bolivia is another country with a history that comprehensively refutes the notion that illicit drugs are always a source of violence.

Whereas most drugs-producing or transit countries today experience violence and conflict, Bolivia is not a conflict-affected state and has no active insurgencies, despite being a major producer of coca and coca paste. What makes Bolivia even more interesting is that it has elected a coca peasant leader, Evo Morales, in the last three presidential elections.

What explains the relative absence of drugs-inspired conflict and violence in Bolivia?

In the 1970s to the early 80s, there were attempts to establish a state-sponsored protection racket but these failed. The biggest drug lord at that time was Roberto Suarez Gomez, a traditional latifundista (large landowner) who owned extensive cattle ranches in Beni and Santa Cruz. These ranches had small airstrips, in which Suarez Gomez maintained an impressive fleet of small aircraft, initially to transport meat to Bolivian capitals, but later to transport coca paste as well to the Medellin drug cartel in Colombia. Following his arrest in July 1988, he offered to pay off two-thirds of Bolivia’s foreign debt, then standing at US$ 3billion.

According to journalist and author James Painter, evidence suggests that Suarez Gomez financed the ‘cocaine coup’ of 1980 which put into power General Luis Garcia Meza, who promptly appointed Colonel Luis Arce Gomez, the drug lord’s cousin, as Interior Minister responsible for anti-drug operations. But the Garcia Meza regime collapsed a year later. By 1984, Bolivia suffered from hyperinflation, and political instability followed. Thus, there could be no state-sponsored protection racket because state officials just did not have the power to construct it.

Still, the absence of the racket, a cause of widespread violence in Mexico, did not lead to violence in Bolivia.

According to academic Stewart Prest, Bolivia enjoyed a ‘rough peace’, or the avoidance of armed conflict in a contentious political context. The answer, he argues, could be found in locally-embedded institutions of governance that solve collective action problems and mitigate conflict.

These institutions include none other than the sindicatos or coca growers unions. Another scholar, Thomas Grisaffi, described sindicatos as self-governing units established by poor settler families in the absence of state institutions. It assumed the role of local governance, and “to this day are responsible for assigning land, administering justice, taxing the coca trade, and undertaking community projects such as building schools or roads”. There are over one thousand sindicatos in Chapare, Bolivia’s main coca growing area. They are grouped into six federations, representing some 45,000 grower families. Morales chaired the alliance of the six federations, which propelled him to the presidency.

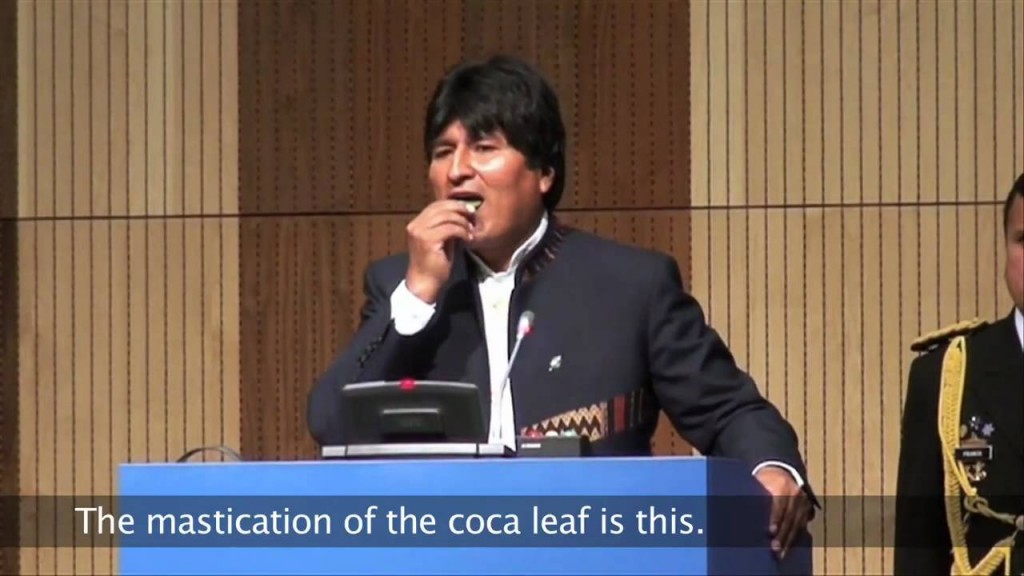

On March 11, 2009, President Morales – who was previously denied visas to attend UN meetings because as a cocalero he was considered a criminal – spoke before a high-level UN plenary session in Vienna. Halfway through the speech, he stunned his audience of assembled ministers and global dignitaries by bringing out a bag of coca leaves mixed with baking soda, and started chewing it. “This is a coca leaf”, he pointed out. “This is not cocaine. This represents the culture of the indigenous people of the Andean region”.

The global legal system and international drug control policy – which are firmly framed by the notion that illicit drugs breed violence and disorder – have much to benefit from a careful consideration of the experience of these countries.

Eric Gutierrez is currently completing the PhD dissertation “Criminals Without Borders: Agrarian Change and Interdependency in Opium- and Coca-Producing Territories” at the International Institute of Social Studies, Erasmus University Rotterdam. This article is excerpted from a chapter in the dissertation.