Alan Blythe, a Cheshire cab driver charged with cultivating cannabis with intent to supply, explained to the court that he had only supplied cannabis to his wife, Judith, a terminally ill multiple sclerosis patient. Where other drugs had failed, cannabis had succeeded in easing her wracking pain. Blythe feared that without the palliative effects of cannabis, she would chose to take her own life rather than live in increasing agony. The judge contended that duress was not a viable defence against charges of cannabis cultivation, and instructed the jury to find Mr. Blythe guilty. After a short deliberation, the jury returned not guilty verdicts on all charges other than simple cannabis possession; while Blythe had faced years in prison, the jury sent him on his way with a small fine.

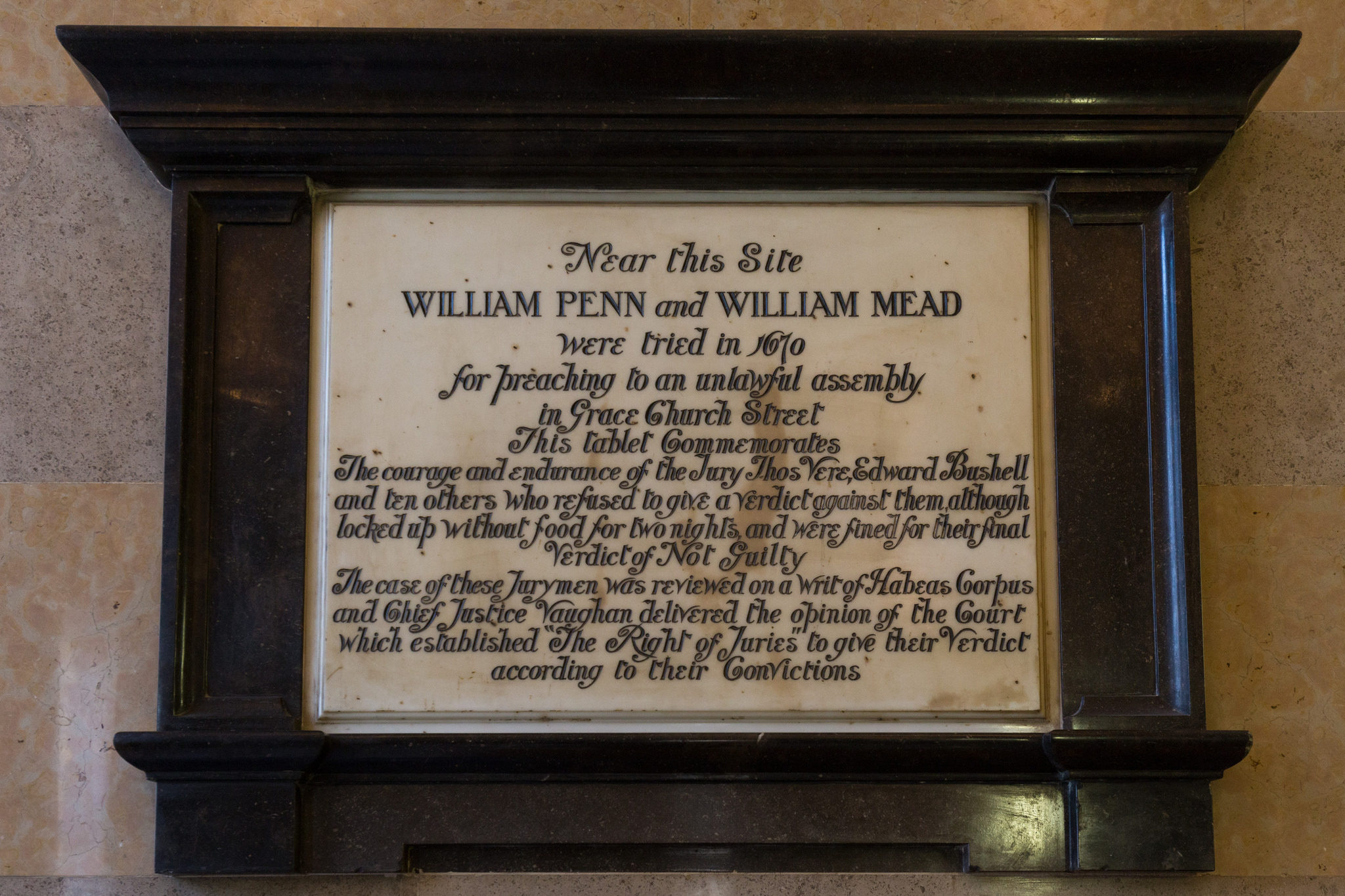

Blythe’s 1998 case is a clear-cut example of jury nullification, or jury equity, as it is sometimes known in the UK. In deviating from both the law’s charge, and the judge’s instructions, the jury exercised its longstanding right to return an independent verdict. Drawing upon a common law tradition of juries as bearers of the community’s law, this right was firmly established in 1670, when a jury refused to convict William Penn on charges of unlawful assembly for delivering a Quaker sermon on Gracechurch Street. After first finding Penn not guilty, the jurors were imprisoned, without food or tobacco, in a bullying attempt to alter their verdict. After they refused to relent, Chief Justice John Vaughn ruled the decision to imprison the jury “absurd”, and released them, upholding Penn’s acquittal while explicitly recognising the jury’s right to return a verdict according to their conscience.

William Penn & William Mead Plaque (Flickr: Paul Clarke)

The jury does not announce the reasoning behind their verdict, so it is often difficult to tell when jury nullification has occurred, however, it generally follows one of two patterns. The jury may acquit the defendant entirely, or return a guilty verdict for a minor, often nonsensical, subset of his charges. The former style may be motivated by a complete rejection of the law, or mistrust of the criminal justice process. It is effectually indistinguishable from an acquittal for lack of evidence.

The second style of nullification is often easier to recognise, cropping up throughout the history of the common law. In the early 19th century England, theft of items worth more than forty shillings carried a death sentence. Juries by no means endorsed theft, but were nonetheless often unwilling to condemn petty criminals to death. A jury from this period famously found a pair of ten pound notes to be worth thirty nine shillings, a finding only explicable by resistance to the casual use of capital punishment. In the prohibition era Dunn v. United States, the US Supreme Court upheld a jury verdict finding Dunn guilty of “maintaining a common nuisance by keeping liquor for sale”, but acquitting him of more serious charges of unlawful possession and sale of an intoxicating liquor. This approach to nullification was again exampled in Alan Blythe’s case.

These split decisions are particularly interesting, because they evidence concern for the rule of law even among jurors willing to set aside specific laws in the name of justice. These decisions signal that while the jury feels some duty to uphold the law, they find the law, or the punishments it imposes, unduly punitive, and ripe for reform. Law functions as a lagging indicator of society’s preferences. It takes time for public opinion to recognisably crystallise, and office seeking politicians wish to be certain of widespread support before staking their reputations on reformist legislation. In the United States, cannabis legalisation has only been passed in referendums. The delay between the recognition of injustice and reparative legislative action renders jury nullification a valuable corrective. Unlike periodic lawmaking, the right of nullification may be exercised whenever an individual is charged with a crime.

While public opinion continues to shift against cannabis prohibition, legislative legalisation remains, at present, out of reach. Nonetheless, jurors aware of their right to nullify may capably prevent individual prosecutions, simultaneously ameliorating, at least in once instance, the carceral harm of prohibition, while sending a strong signal in favour of legal reform. In the face of frequent nullifications, prosecutors opt to simply stop charging citizens for violations of cannabis control statues. In the face of repeated refusals to convict defendants on cannabis possession charges, Montana judge Dusty Deschamps conceded that “it’s going to become increasingly difficult to seat a jury in marijuana cases, at least the ones involving a small amount”. While prosecutorial reticence does not in of itself alter the law, it alleviates at least some of the harms of prohibition, condemning fewer users to prison at the taxpayers’ expense.

Unfortunately, most jurors are unaware of their right to acquit the defendant for reasons of conscience. In some cases, potential jurors may be struck from the jury pool for expressing an intent to nullify. Solicitors, empowered as officers of the court, are hesitant to purse nullification given their obligation to “uphold the rule of law and the proper administration of justice”. Furthermore, nullification is a risky strategy. Instead of disputing the state’s evidence, a defence attorney attempting nullification must place his client entirely at the mercy of the jury. In many cases, this style of defence may considered a dereliction of the solicitor’s duty to act in the best interest of their client.

Nevertheless, known or not, the jury’s right to return an independent verdict remains. If you find yourself on a jury, remember that you need not support an unconscionable verdict, even if instructed to do so by the judge. The jury is an independent body, empaneled to both judge the weight of the evidence, and ensure that justice is done. If a strict application of the law serves to create, rather than rectify, injustice, you have the right to say no. Britain’s war on drugs has left thousands imprisoned, or cast out of the labor market due to past convictions, but thanks to the courage of a Cheshire jury, Alan Blythe is not one of them. Until prohibition is ended, nullification will remain many a defendants’ last, best, hope.

William Duffield is a Masters student in Political Theory.