In December a new report undertaken by the Scottish Drugs Forum and Glasgow University was delivered to the Scottish Government. In it, researchers have shed a light on an often misunderstood area of drug use – Novel Psychoactive Substances.

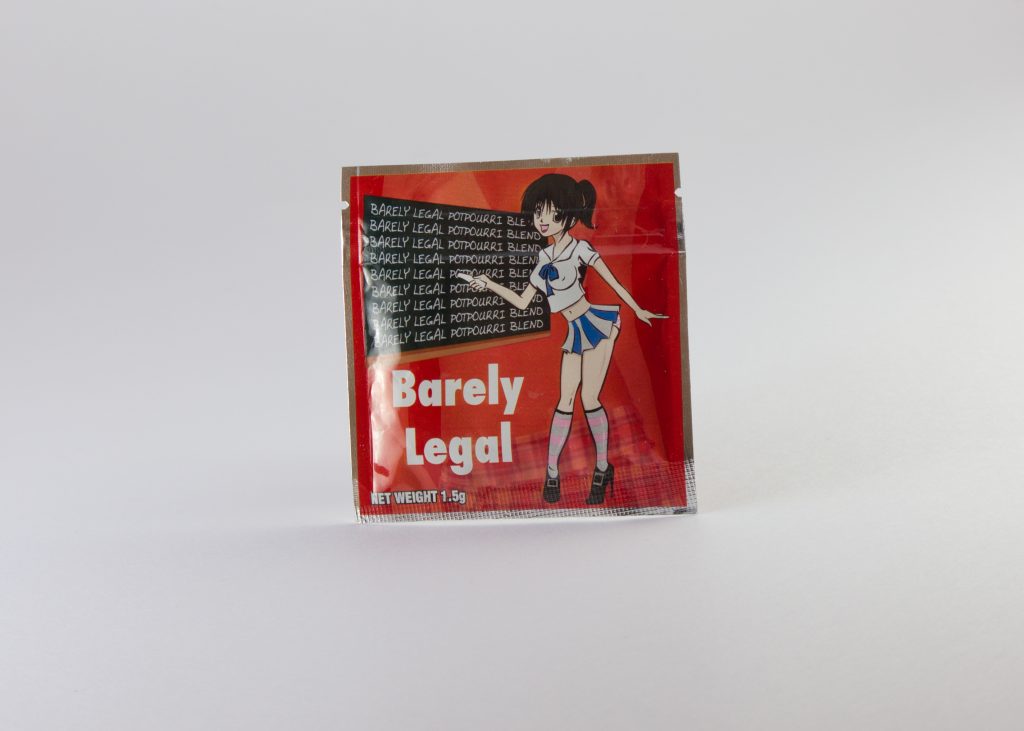

These drugs – often wrongly termed ‘legal highs’ – grew enormously in popularity and availability over the past 5 years, so much so that the government, in a typically ham-fisted manner, rushed through legislation earlier this year to ban them all. From Salvia to the wide range of synthetic cannabinoids known generally (and again wrongly) as ‘Spice,’ a huge number of products were outlawed overnight, with little care as to whether or not they were dangerous, or how the new law would actually work in practice.

The research that informs the new SDF report (which you can find a download link to on this page) was largely undertaken before the new law – the Psychoactive Substances Act – came into force, and as such cannot offer too much insight into the effect of the blanket ban on users. But what it does do is provide an insight into three key areas: patterns of NPS use, motivations for and consequences of use, and treatment and legislative responses.

To do this, researchers carried out a series of interviews with both users of NPS and frontline staff from across NHS Scotland who work with those users. Though long, and dry, and far from an easy read, once the salient findings are extracted from the report their significance is clear.

For example, one of the key findings of the report was that 36% of all of the NPS users surveyed were not in contact with drug services for any issue at all. Of those that were, only 11% reported being in contact with services specifically related to their NPS use. It would be nice to think that this is because they didn’t need help. Indeed, when it comes to more traditional drugs, it is an oft-repeated fact that only around 10% of all drug use is problematic. Unfortunately, however, that number is often considerably higher among users of certain NPS, particularly synthetic cannabinoid mixes like ‘Spice’ and ‘Black Mamba’ that are currently ravaging swathes of the UK’s prison and homeless populations.

This worrying lack of contact with the services designed to help NPS users has a number of causes and ramifications.

A lot of users reported never having tried to access information about the drugs they were consuming, and underreporting of use is believed to be a serious barrier to effective treatment. The reasons for this are twofold – firstly, it is undeniable that the services currently available are inadequate. There are not enough staff, and those that there are do not know enough about the drugs people are taking to be of much use, due in large part to the ever-changing nature of the drugs themselves. Chemists at home and abroad are constantly tweaking the molecular structure of their products to circumvent laws – something the PSA aimed to put a stop to – and also to beat drug tests.

I spoke with Katy MacLeod, lead author on the study, who shared a telling quote from one of the interviewees. “they [drug services] knew bits and pieces about powders and pills but they didn’t know enough about synthetics [cannabinoids] to help me.”

Katy continued, “Staff also identified the challenges of keeping up to date with information, one worker shared “because there’s such a plethora of different chemicals and changing chemicals, what are you going to do?””

Secondly, drug use of all kinds has always been underreported simply because of the stigma associated with it. This will not change as long as users are considered ‘other,’ and drugs remain illegal and underground. People do not like to admit that they are breaking the law, or partaking in substances which society at large has deemed inappropriate or illicit.

Another reason for the underreporting of NPS use was elucidated by MacLeod. There was, she explained:

[..] a lot of confusion amongst people who used NPS about what constituted as an NPS which could be further complicated by the merging of NPS with the traditional drug market post PSA. Without access to drug testing, people do not know what they are using and there has been evidence of various types of NPS sold as traditional drugs which makes accurate recording of what people are using impossible.

A major ramification of the lack of contact between users and service staff is that there is a major disconnect between the two. This is a theme that comes up again and again within the new report – what the users are saying to the researchers about how they perceive the harms of their drugs of choice, about prevalence, and about the motives behind their use, is in many cases vastly different to what is perceived by frontline staff. Again the reasons for this boil down to a lack of education and the inherent difficulties of trying to understand a drug market that is by its very nature secretive and hidden from view. It is also a self-fulfilling prophecy – because users of these drugs know full well that the drug service staff are themselves under-educated on the subject, they are less likely to seek help, further fuelling the problem.

As mentioned earlier, the majority of the research for this report was undertaken before the Psychoactive Substances Act came into force. However, it was known at the time that the government’s ban hammer was poised to strike. As a result, researchers were able to ask users and drug service staff their opinions on the Act, and the report offers some unsurprising but important conclusions.

The crux of those conclusions was simple: the Psychoactive Substances Act will not, in all likelihood, have much of an effect on use. If anything, it is likely to cause harm, particularly to those most vulnerable.

Over 25% of NPS users surveyed for this report told researchers that once the new ban came into force they would simply return to using more traditional drugs. This should hardly be surprising, but it is dangerous.

Not only will the law not be helping these people to reduce any potential harm caused by their drug use, it may well be putting them at increased risk. Users of previously-legal opiate-like substances, for example, who decide to simply move back to using heroin, are likely to find that their tolerance levels are no longer the same, raising the risk of overdose substantially.

Katy MacLeod, who led the research for Scottish Drugs Forum, said:

NPS use amongst these groups is complex and results in a number of harms and specific treatment needs. This research is important because it provides a tentative first understanding of use amongst vulnerable groups, alongside motives and consequences of use amongst vulnerable groups in Scotland. Challenges for services include encouraging disclosure of NPS use and allocating resources to those requiring treatment for NPS use. Equally offering tailored information to people who use NPS from a range of vulnerable groups is important in order to reduce harm.

With many factors likely to influence trends within NPS in Scotland, including the Psychoactive Substance Act, services will need to be vigilant around increased overdose risk for people who may move or return to traditional drug use.

Those who continue to use NPS could find themselves in a similar position, as the dealers who inevitably fill the void left by headshops end up selling them whatever makes them the most money, regardless of danger. Users of traditional drugs who haven’t previously used NPS could be at risk too. Recent anecdotal stories suggest that cannabis dealers in some areas are lacing their product with synthetic cannabinoids in order to make more money, and in doing so are landing unsuspecting cannabis users in hospital.

The report also looks at the motives behind NPS use, and highlights price, ease of access, curiosity, and the influence of peers as key reasons behind use. Interestingly, as Katy MacLeod explains:

Legality isn’t a driver for use, people tend to stop using where they experience harms and almost everyone in this sample use illegal drugs anyway. This gets away from he tabloid impression of legal highs being used by people that wouldn’t otherwise use drugs.

But what is important is to look at the issue in a wider context. The factors that do drive people to drug use of any kind – including NPS – have been ratcheted up in recent times and have left large numbers of people vulnerable to their potentially destructive influence.

Homeless people are a key demographic, and with homelessness on the rise across the UK, driven by austerity cuts, lack of social housing, and particularly loss of benefits and jobs, we have seen a corresponding rise in NPS use and harm. The Psychoactive Substances Act does little to address this, and by its very nature makes it more difficult for the homeless and other at-risk groups to seek help. A problem which is then confounded by the lack of information and drugs services.

Social conditions and existing drug laws created the perfect breeding ground for addiction in vulnerable communities, and whilst it is important to understand patterns of use among NPS users, their motives for using these drugs, and the harms that the drugs cause, it is essentially futile if we do nothing to address the root causes of drug abuse in our society.

Groups such as the Scottish Drugs Forum are attempting to do this, and this report offers very useful insight into NPS use in Scotland and the serious barriers preventing users from accessing information and professional help. But whilst they acknowledge the need to monitor the impact of the PSA, they do not go far enough in condemning the impact it is already having and that we know from experience it will have. Until they do that, all research of this kind – useful though it is – is likely to be in vain.

The impact of the PSA has been felt across the UK, from the former Head Shop owner in Exeter who overdosed on his own stock after the law forced the closure of his business, to prisons all over the country which are buckling under the weight of addiction and drug abuse within their walls. The terrible truth is that we know it is failing, and we know why. But until politicians start to focus on the inherent failings of their own drug policies, instead of commissioning research after the fact that will not heal the damage already done, we will merely be applying a sticking plaster to a much deeper wound that can only begin to be healed by serious drug policy and social justice reforms.

Deej Sullivan is a journalist and campaigner. He regularly writes on drug policy for politics.co.uk, London Real, and many others, and is the Policy & Communications officer at Law Enforcement Against Prohibition UK. Tweets @sullivandeej