Earlier this week, David Cameron’s former policy advisor – Paul Kirby, shared his provocative proposals for penal reform in the UK.

Kirby’s ideas are interesting in theory, but how would they work in practice? Andrew Neilson of The Howard League for Penal Reform responds to Paul Kirby…

There is a very welcome surge of interest on the topic of prison reform right now, led by the appointment of Michael Gove as Secretary of State for Justice and the recent speech on prisons by the Prime Minister.

And there is certainly plentiful evidence of the need for such reform, evidence the Howard League has to deal with every day as part of our work as a charity with an interest in prisons.

One of the most interesting elements of David Cameron’s speech was an acknowledgement of the human cost of failing prisons. Usually when politicians talk about prisons they focus on technocratic discussions about reducing reoffending. But Cameron also put to the foreground a humane argument and pointed to the recent rises in violence and self-injury behind bars.

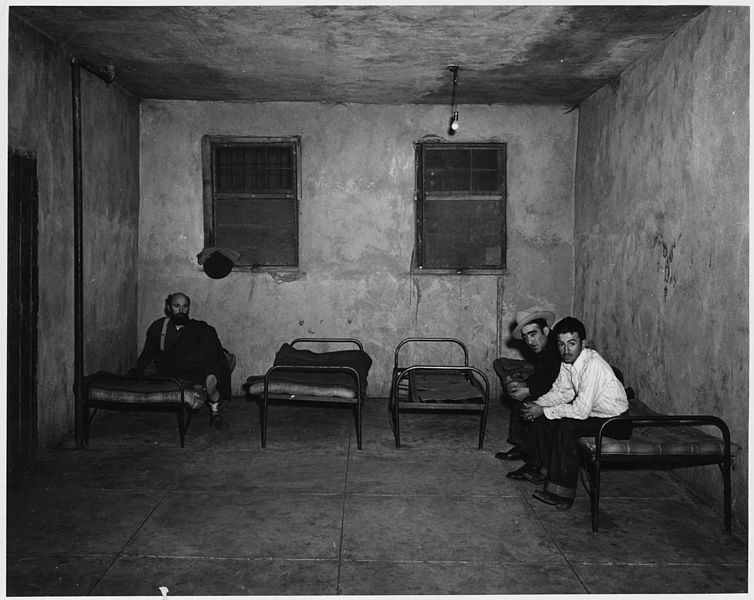

The rate of suicides in prison is at a ten year high. There were more homicides behind bars in 2015 than in any other year on record (eight). Incidents of self-harm by male prisoners increased by 30% in the space of twelve months. These are facts that should rightly warrant action.

Paul Kirby’s recent piece on VolteFace advances some policy ideas on this topic. Kirby is a man we should listen to, given he has worked for both Labour and Conservative governments and is a former head of policy in Downing Street.

There is no doubt that part of the problem with the debate on prisons is the generally punitive cast of public opinion and Paul Kirby is on to something when he identifies that the public thirst for imprisonment has, in part, come from the abolition of both capital and corporal punishment. It is also worth saying however that the public can have quite contradictory views when asked about prisons and the criminal justice system more widely. When polled, many people also express a desire for the system to rehabilitate. Yet there is little recognition that these two principles: punishment and reform, as the Ministry of Justice has in the past described its mission, are fundamentally contradictory. If you want people to change for the better, then punishment hinders that. Paul Kirby rightly identifies some of the myriad ways imprisonment ends up making people worse.

To paraphrase George Bernard Shaw (himself a penal reformer): “the road to hell is paved with good intentions” – and penal reform has long been haunted by these words.

The Quakers, who arguably invented the modern notion of the prison with their American penitentiaries, thought that putting people into solitary confinement would lead them to contemplate their wrongs and find God. Nowadays we recognise the terrible damage to mental health that solitary confinement can cause and seek to limit its use whenever possible (although it is still overused in our prisons).

With that in mind, I want to respond to some of the ideas advanced by Paul Kirby: the use of house arrest, deferred sentencing/flexi-prison and hard labour. We can have good intentions to reform the system and make it more humane and more effective. But coming back to that fundamental tension between punishment and reform, those good intentions can be distorted as the tension plays out in practice.

House Arrest

Putting people under house arrest is not a new idea and we already see curfews as part of community sentencing. But expanding the concept of prison to include house arrest is dangerous indeed.

If we accept that prisons lead to the bad outcomes that Paul Kirby describes, then why on earth would we want to turn people’s homes into prisons?

More concerning is how you would regulate and monitor what then happens. Paul Kirby rightly says that prisons are a modern phenomenon, not really much more than 200 years old. Another way of looking at it is that prisons are in fact quite unnatural institutions and being imprisoned is an unnatural state for human beings to be in. That is one reason why we should think carefully before sending people to prison.

If we look at what happens when people have their liberty taken away from them, the unnatural situation they are in begins to embody itself in each individual’s behaviour. They act in unpredictable ways. It affects their mental health. All too often, they self-harm. Or they try to escape, or find solace in drugs and alcohol.

Prison staff are well-used to attempting to police and deal with these issues. Even they struggle to do so, however. So I cannot see how you can practically do the same with people on individual house arrest in potentially thousands of homes up and down the country. You wouldn’t be able to stop a suicide attempt from the other end of a webcam!

Deferred Sentences / ‘Flexi-Prison’

The idea of conditional sentencing, on the other hand, has a lot of potential and could play a part in the ‘problem-solving courts’ that Michael Gove is interested in. A great deal depends, however, on how much we can expect from people before those courts.

Many of the people filling prisons on short sentences, who don’t commit serious crimes but are committing numerous repeat offences, lead very chaotic lives. They have a huge range of problems and getting them to desist from offending is going to take a lot of time and effort.

There isn’t a simple on/off switch. Sometimes progress is measured in getting someone to offend less seriously or frequently. A conditional sentence that recognises this – where the court can perhaps moderate the conditions according to the individual’s situation – could be a powerful tool for reform. Otherwise, it just becomes another way of setting people up to fail.

‘Flexi-Prison,’ as Paul Kirby calls it, is an idea that is apparently being considered by the Ministry of Justice and which has been trialled in the past. The obvious objection to it is that if someone is considered safe enough to be free in the community from Monday to Friday then why would we lock them up at weekends? More practically, the problem is that if you are locking someone up at weekends then you will need a prison cell and that cell will be empty from Monday to Friday. This may not be the best use of public money at a time when that money is tight.

Then again, there is potential for scheduling the commencement of certain prison sentences rather than immediately sending everyone to prison from court. It could be helpful in allowing some people to make arrangements that keep them in employment, for example.

In Scandinavian countries where weekend imprisonment has been used, it was often for middle class drunk drivers or tax evaders, so it could be considered here to respond to public outrage at the very rich not paying their dues.

Hard Labour

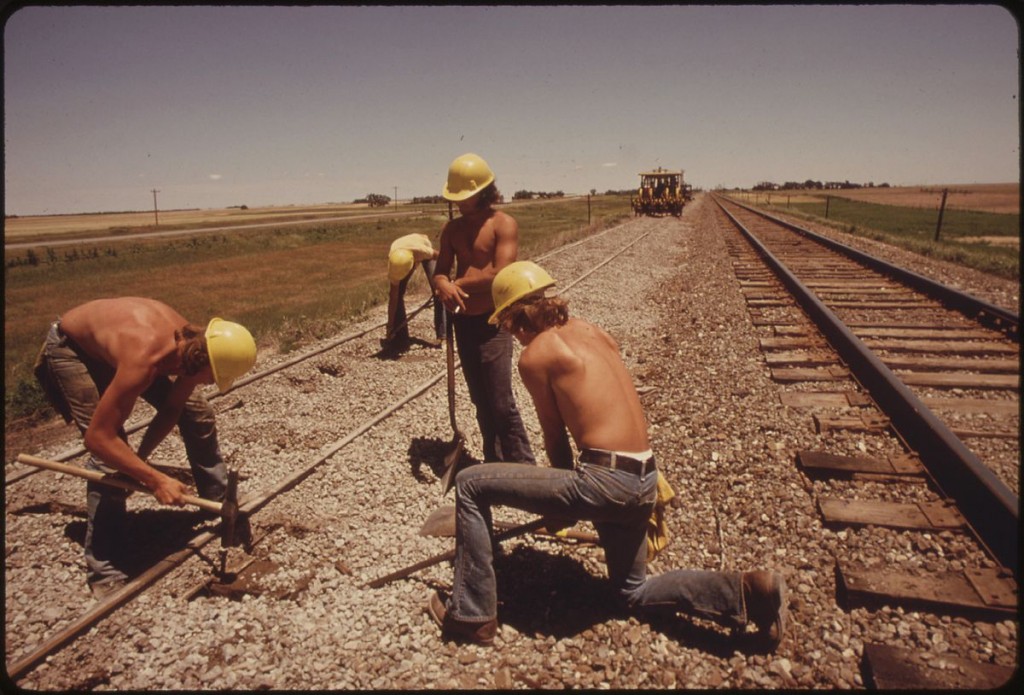

Making prisons places where work happens rather than places of enforced idleness is a good idea. It is something the Howard League has long been interested in. But we would argue strongly that enforced ‘hard labour’ is very much not the answer. Indeed, it was specifically abolished in the UK following the experience of the Second World War concentration camps and should not be something we return to.

If the detention of liberty is the punishment meted out by the courts by sending someone to prison, then we should not be adding to that punishment by forcing prisoners to work in the way Paul Kirby describes. It would also devalue unpaid work as part of a community sentence – upping the punishment in prison ante and weakening an alternative to imprisonment, at a time when the prison population desperately needs reducing and prison regimes need to be more rehabilitative.

More importantly it fundamentally devalues the concept of work itself. We should be making prisoners fall in love with work, not making them hate it even more by forcing them to work for no remuneration. The problem with prison work at the moment is that much of it is desultory, repetitive and poorly paid. The answer is not to remove any notion of a salary but to make work in prison more like work in the community. It should be engaging, more varied and better paid.

Businesses should be invited into prisons to train and employ prisoners, paying them a decent wage so they can remit money to their families or save for their release. Some money could go to victims. Prisoners could pay tax and national insurance. On release, those prisoners could go work for their employer in the community. This might sound like fantasy but the Howard League actually ran a graphic design studio in a prison for many years that did just that [Editor’s note: ‘The Clink’ restaurant in Brixton – staffed by inmates – also comes to mind].

Partly through our experience and partly through a cursory glance at the long waiting lists for almost every available job in prison, we can see that the overwhelming majority of people prison really do want to work. We don’t need to force these people to work, we need to provide more and better opportunities that can actually reflect work on the outside.

A New Paradigm For Criminal Justice

Paul Kirby runs through what are often described as the various purposes of imprisonment: retribution (punishment), rehabilitation, deterrence and incapacitation. Of these, he is right to single out punishment for particular attention, as it is the one undebatable outcome of imprisonment. Taking away somebody’s liberty is most definitely a punishment.

Whether prison can really rehabilitate, deter or successfully incapacitate is often less clear.

Kirby is wrong, however, to assume that it is punishment that needs to be reinvented. Yes, public attitudes are often punitive (although there is plentiful evidence the public are considerably less punitive when they are engaged with the individual details of cases) but they have not been altered by our prison population doubling over the last two decades. Policymakers should be wary before jumping on the punitive populist treadmill. No matter how fast you run, the treadmill will make you run more.

Instead, and despite the difficult polling, the public need to be engaged on how things can be different.

We are seeing something of that in Michael Gove’s rhetoric since taking over at the Ministry of Justice, in his emphasis on redemption and forgiveness. And with that spirit in mind, I want to offer a fifth possible purpose – not so much for prison but for the justice system more generally: that of reparation.

The system needs to offer more opportunities for people to repair the damage they have done and to make amends.

This is not just about restorative justice, where victims and offenders meet – although that is a powerful tool which has high rates of satisfaction among both groups that participate in the process. It is about restorative approaches more generally. It is about creating opportunities for reparation at every single possible stage of the process: from when police first consider arresting someone to the decision to prosecute and then all the way to a person being sentenced to imprisonment in court.

Such restorative approaches are already increasingly used in policing. The Howard League has done a lot of work on encouraging police forces to move away from target-driven policing and use more discretion to reduce the criminalisation of children. Police forces are now far more likely to try and resolve misbehaviour on the spot, where possible involving families or if needs be welfare agencies. The result has been the number of child arrests falling by 54 percent since 2010 – meaning thousands of fewer children have been criminalised and securing long-term beneficial impacts for society because each of those children is now less likely to become the adult prisoner of tomorrow.

Paul Kirby rightly says that we need more community involvement in criminal justice, in his discussion on Japanese probation volunteers. A system focused on reparative and restorative principles would take into account the harm victims and wider communities have experienced and do more to repair damage and allow everybody to move on. It could harness volunteering and democratic engagement. Creating an in-built tendency towards selecting the most reparative option wherever possible, rather than the most punitive, could be a powerful basis for reform.

Andrew Neilson is Director of Campaigns at the Howard League for Penal Reform

Last week, Michael Gove set out his vision for UK prison reform – read our coverage

Also, read our Editor in Chief ‘s call for a new conversation around drugs and prisons, and our eye-opening interview with former-inmate-turned-expert Alex Cavendish of Prison UK