The psychedelic renaissance is afoot, and there’s almost no use arguing with the term anymore. It’s just too catchy. This elegant phrase pops up frequently to describe what’s been happening in the United States, the United Kingdom, Brazil, and around the world in the 21st century.

In addition to being the title of an excellent book by Ben Sessa, the two words serve as a catch-all for a whole host of phenomena: the medical studies occurring on both sides of the Atlantic and beyond, the globalisation of the South American brew ayahuasca, microdosing LSD in the workplace to crack open the doors of perception, iboga as addiction interrupter, the widespread legalisation of cannabis, therapeutic access to MDMA, the spread of drug-selling dark web cryptomarkets, an evolving therapeutic vocabulary, a new availability of LSD, an ever-networking global community, and more. But the phrase “psychedelic renaissance” itself is worth investigating, meaning perhaps more than it intends.

“The psychedelic renaissance is no bicoastal hype,” wrote David Fricke in Rolling Stone in 1985. He was referring to the revival of ‘60s cultural tropes, mostly by bands in the so-called Paisley Underground, a genre of indie rock burbling out of Los Angeles in the ‘80s. Entheogenic supporters have been busy declaring a “psychedelic renaissance” since at least 1986, when it was reported in a book about neuroscience by Omni editors Judith Hooper and Dick Teresi. It then turned up as a photo caption in Newsweek the next year and spread as literary spore from there. Invoked in the ’90s to describe the ’80s and in the 2000s to describe the ’90s, the durability of phrase illustrates something vital about itself, about the raw power of psychedelics to inspire those involved with them to declare renaissances. Or waves, springs, or some other eloquent metaphor of renewal. (1)

More often than not, this invocation is used to assure the intended audience that the present situation–whenever the present may be–is to be differentiated from the controversial and dark period(s) that preceded it – periods when psychedelics were cheap and plentiful on the street. Dark periods like the ’60s. And the ’70s. And the ’80s, and ’90s, too. But most especially the ’60s.

What’s different about the psychedelic renaissance of the 21st century, of course, is that it’s here and actually happening, with once marginalised ideas entering the mainstream in legitimate ways. All of the above-listed developments are occurring with unprecedented post-millennial openness, weaving into global culture in a manner that–along with the ongoing legalisation of cannabis – suggests a gradual ceasefire in some battlefields of the war on drugs. It might even suggest genuine full cultural integration, always a buzzword in psychedelic communities, with its distinct overtones of the Civil Rights movement.

What’s not different about the psychedelic renaissance of the 21st century is the complete and total faith of those involved. To invoke a psychedelic renaissance is to both cast a forgetful spell on the past, and to do something completely in the tradition of the psychedelic renaissances of yore by creating a slogan that says (and does) what former Harvard professor Baba Ram Dass suggested in the ’60s: Be Here Now.

But what might actually be significant about the psychedelic renaissance of the 21st century is that it’s the first psychedelic renaissance from which the past can be viewed from a useful vantage point. With longtime practitioners less hesitant to share their stories, alongside an increasingly nuanced public dialogue on gender, race, addiction, mental health and more, it is a psychedelic history that is (like all of history) open to constant re-examination with all the new tools and perspectives available to contemporary scholars. It’s possible that, this time, people won’t forget.

Psychedelic history matters because, a half-century removed from the spread and mid-’60s criminalisation of psychedelics, it is possible to view the long arc of the psychedelic story and see the emergence of a coherent but flexible non-denominational spiritual system throughout the English-speaking world, with its own traditions and techniques and body of literature. And it is possible to measure how this has had an ongoing impact on technology, on arts of many varieties, on personal wellness, on the structure of businesses, on architecture and fashion, on an ongoing counterculture. It has also impacted spirituality itself, both as an end but also as a seemingly permanent bridge to more traditional belief sets.

With psychedelics returning to prominence in numerous fields, an awareness of their broader cultural history becomes even more important. Psychedelics are a contested science and their active use by a small but devoted population–estimated at perhaps 1.2 million people in the United States in 2014 according to the National Survey on Drug Use and Health–is one of the reasons they remain contested. During the next years, many will undoubtedly engage in psychedelic use as a form of civil disobedience, seeking internal freedoms far from any type of government control, and many more will undoubtedly reframe and rethink the countercultural conditions with which psychedelics are most often associated.

Alongside the new perspectives comes new documents. In unexpected ways, the past is always changing. Studies and articles and anecdotes scattered in myriad journals and newspapers and memoirs can now be connected for the first time by the web-crawling indexing bots of search engines. Hindsight has always been 20/20, but the new modes of detailed research available through Google Books and other ever-opening archives give it a sheen that is perhaps even better, a hyperreal vision of the past as a rich and always unfolding text. New mediums and platforms offer opportunities for serendipitous collisions by scholars, their projects, and even their primary subjects. Facebook and other social media networks make connecting to long-missing figures easy. There has never been a better time to be a contemporary historian. As with all of the new adventures in research come ongoing ethical questions: Just because something is online, is it acceptable to use it as a source?

Besides the wide variety of substances and practices, what complicates psychedelic history and makes a single definitive narrative impossible is both its criminality and the personal natures of its use, factors inseparable in most of western society. Even LSD’s 1943 discovery by Albert Hofmann is cloaked in mystery and subjectivity, as David Nichols has pointed out, with nearly every twist in the psychedelic history veiled by further mythologies, disinformation, and continued needs for privacy, from the nature of various governments’ 1950s and 1960s experiments to the darkest depths of the Drug War. Psychedelic history is secret, for the most part, and when it’s not, it demands at least some amount of nuance. These complications in turn play large roles in shaping the way psychedelics move into the modern world and the way scientific research itself is being conducted. In Rick Strassman’s The Spirit Molecule, the DMT researcher vividly recounts how his early ‘90s project involving the powerful psychedelic DMT created friction within his local research and spiritual communities, shifting the work itself in quantifiable ways.

Salvia divinorum was a psychedelic used in religious ceremonies with a Christian influence. (thepsychedelicscientist.com)

But psychedelic history is getting less secret every day, thanks in part to the internet’s power to serve as a macroscope.

Stories once locked in private places now wind up in mysterious online corners for purposes that aren’t always transparent. As historian Michelle Morevic points out, a fundamental difference between researching online and researching in a physical archive is the intense physical context of the archive and the document’s place within it. Searched digitally, it is easy to conjure a piece of data or quote or anecdote without regard to its place in its original source. But online historical work provides a different kind of structure, a picture emerging in old newspapers, message board postings, phone books, over multiple careers and identities. But increasingly, the stories are breaking loose from their sources.

In 1967, the Haight-Ashbury-based Richard Brautigan published his poem “All Watched Over By Machines of Loving Grace” through comm/co, the broadsheet-producing publishing arm of San Francisco’s radical Diggers collective. Brautigan dreamed “of a cybernetic meadow / where mammals and computers / live together in mutually / programming harmony.” It was a signal moment for the counterculture, an invocation that fused longhaired utopianism with the fate of computers. Thanks to a spectrum of new tools that ranges from Google’s deceptively simple search functions to complex collaborative historical projects, such as the big data crunching occurring under the academic umbrella of the Digital Humanities. The cybernetic meadow has arrived in the academy.

A fashionable phrase to describe new data scraping tools, “digital humanities” covers a wide variety of practices that perform analysis of large bodies of historical text. It is in recent years that the psychedelic humanities are perhaps now achieving a state of maturity with bodies of text large and consistent enough to allow for substantial processing. One that stands out are the massive drug experience archives, hosted by Erowid and other sites, where drug users file trip reports. They’ve already been sliced into a number of decontextualised Twitter accounts, such as @Pharmaduke (mashing up trip reports with Marmaduke cartoons) and @SarowidPalinUSA.

“What we need now are the diaries of explorers,” Terence McKenna said in the early ’90s. “We need many diaries of many explorers so we can begin to get a feel for the territory.” Now, a quarter-century later, that’s exactly what the psychedelic world has. Papers have drawn on these reports before, such as Andrew Gallimore and David Luke’s “DMT Research from 1956 to the Edge of Time,” using a multitude of reports to quantify some of the more archetypal imagery experienced by users.

But the experience reports seem to invite all kinds of abstract sorting, including by substances, terminology used, poly-substance effects, or any type of other core dive. The vocabulary of the psychedelic world has changed numerous times over the decades, with entheogens or medicines or sacraments or any number of substitutes taking the place of the oh-so-basic “psychedelic.” Lately, “journeying” or “journey-work” have grown in popularity where “tripping” once sufficed. A sort through Erowid’s reports–or the anonymised text of public message boards like Reddit or the Shroomery–could reveal any number of evolving linguistic themes. Combined with the powerful mission of Psychedelic Information Theory, which aims to evaluate “the spontaneous production of complex information in the human organism” (such as Terence and Dennis McKenna’s infamous download at La Chorrera) these resources provide any number of data sets ready for holistic abstraction.

Without official recognition, Erowid especially has maintained themselves at the level of an institution, providing a framework for what is largely thought of essentially as a body of folk knowledge.

But by providing a home for the wide array of scientific and more esoteric literature, Erowid transforms it into a vaster unit and generates a larger meaning, the very function of an archive or library. On a more scientific front, Erowid also hosts the reports from PiHKAL and TiHKAL, books by Alexander and Ann Shulgin, encompassing their own humanistic database-like framework to assess their (and others’) experiences with a complete spectrum of psychoactive materials.

But these are only some ways to engage the emerging body of material that might support psychoactive historical research. From the pages of underground newspapers–such as the Babylon Falling collection recently acquired by the Interference Archive–one might draw out a history of drug slang. Or, using the papers’ frequent pages devoted to street drug prices, one might also map out the month-by-month real-time circulation of new strains of cannabis or types of LSD blotter. This type of large-scale data abstraction might complement more controlled lab studies to create a fuller picture of how psychedelics work.

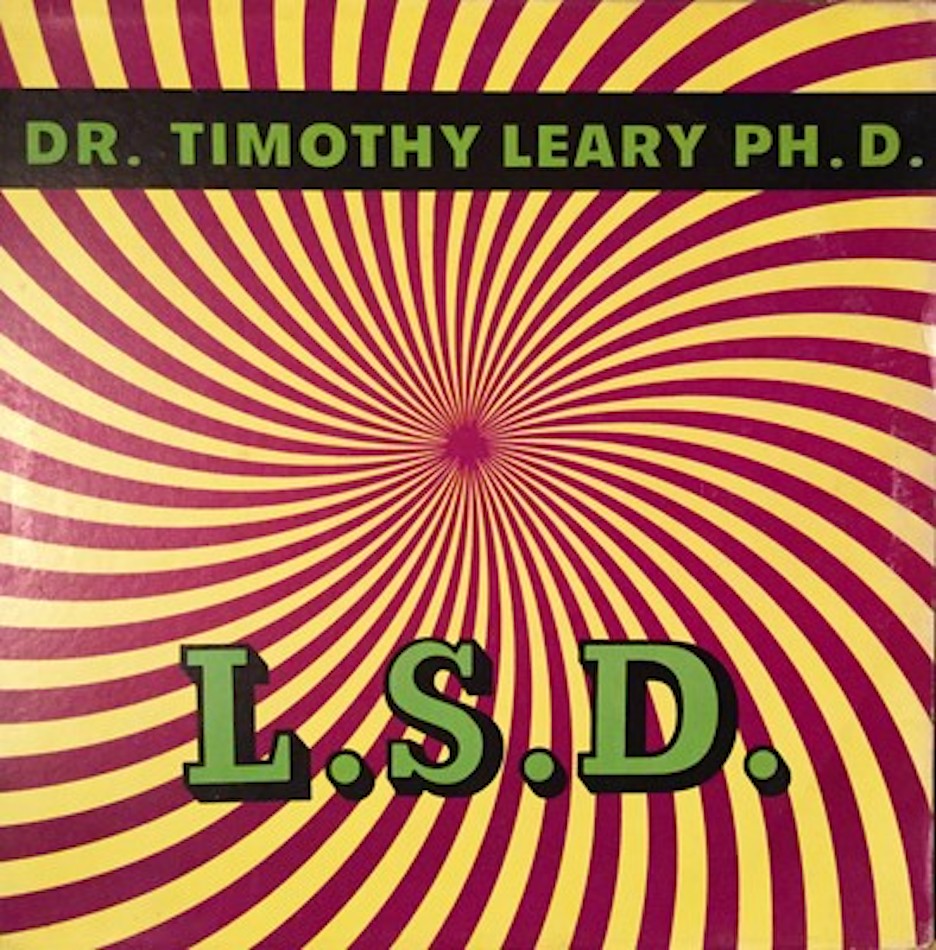

In the same way that 2C-B was accepted as such, LSD likewise underwent a similar folk-knowledge evolution, hitting the mainstream in the past few years in the trendpiece-friendly form of microdosing, as outlined by veteran psychedelic researcher James Fadiman. While Fadiman’s methods are only a half-decade old, the evolution towards smaller doses of acid has been ongoing, beginning in the late 1970s and early 1980s when underground LSD distributors began to scale back from approximately 250 micrograms per hit to 150 and 100 and even lower, in large part because the Owsley-era “God dose” standard of 250 micrograms was collectively deemed to be, perhaps, a bit too strong.

While the plant medicines of ayahuasca and mushrooms have received much attention in recent years, the chemical natures of LSD and 2C-B and others root them in a more industrial age.

Where plant medicines often have long-established practices and accompanying belief sets, lab-synthesised psychedelics rarely possess such contextual weight. As LSD did in the United States starting in the ‘60s, as 2C-B has done in South Africa, they are free to form their own paths without upsetting traditional cultural economies.

During these last few years, with so much attention rightly given to the globalisation of ayahuasca and the return of psychedelic research, the troubled lineage of LSD use has been comparably overlooked, perhaps even self-consciously swept under the rug. But, transcending the diversity of experiences, it has become obvious that all of the new developments pertaining to psychedelics are the product of a shared and coherent history that will continue to shape public policy, public perception, and the unregulated practices of users. Even if psychedelics do become a regulated part of therapeutic practices, the vast majority of users will almost always lie outside that realm.

It is this secret history that is most in danger of disappearing, but also the most ready for chronicling. In the United States, a nearly infinite library of court documents await only hands with scanners and well-phrased Freedom of Information Act requests. Ready to be liberated and dumped online, these documents might be parsed and searched for the first time, crawled by interested archivists and indexing bots alike. In addition to possessing the invaluable Wayback Machine, the Internet Archive’s mechanism for preserving old web pages, the Archive also plays home to a constant stream of FOIA documents, all scanned in their entirety. Last year (for example) saw the arrival of some 9,400 pages of text pertaining to the Los Angeles branch of the American Civil Liberties Union, in turn tied to many other pockets of the ’60s L.A. counterculture.

The contemporary age of psychedelics is fusing seamlessly with the world of big data, as post-Silk Road iterations of the dark-net cryptomarkets churn out an endless supply of numbers to ponder. There’s all kinds of crunching to be done, and lessons to be learned. One recent theory suggests that the cryptomarkets aren’t fueling the global drug trade nearly as much as various intra-continental trades. Out on the forums of various marketplaces, users establish testing groups, descendants of the original LSD Avengers, reporting on the dosages for sale by vendors. Each and every metric suggested by the cryptomarkets poses the questions of how one would measure the same variables in the earlier epochs.

Investigating the history of psychedelics will always reveal the limits of historical techniques, when trails run cold as they approach subjects who don’t want to be found. Misinformation is frequent and intentional, memories are blurry and not always reliable. Like science fiction, the study of history has more to do with the present than its ostensible subject. For some scholars (and administrators), “digital humanities” promises a world of quantifiable strategies and approaches to historic texts. For psychedelic historians, the techniques and results might yield new kinds of seemingly contradictory blurriness, the same type of giant question marks that psychedelics themselves often create, revealing a part of the past that changes as fast as the present.