York Road is the epicentre of homelessness in the Essex seaside town of Southend. Walking east, away from the High Street, you’ll spot groups of guys huddling in the car park, an abandoned supermarket trolley full of clothes and the telltale pair of shoes hanging from the telephone wires. Sometimes you’ll catch odd-smelling fumes of Spice smoke being carried in the air.

Further down the street lies a support centre run by local homelessness charity HARP, which is often their first point of contact with the town’s rough sleepers. Inside, manager Neal McArdle explains that he’s had to deal with many service users suffering from the effects of Spice, from fits and hospitalisations to people running up and down the street possessed.

“Historically, people haven’t seen Spice as an issue, like putting salt on your chips,” Neal says. “But that’s changing. With Spice people are starting to realise they have no idea what they’re smoking.”

In the corridor, Charlie, 20, nods his head in agreement. “It’s like crack but a lot worse,” he says, revealing that he’s been hospitalised seven times due to Spice. “I wanted it so badly I punched a brick wall.”

Spice has become the misleading, catch-all term for a family of different psychoactive substances that have emerged since the mid-2000s. We’re now seeing the third generation of what scientists call Synthetic Cannabinoid Receptor Agonists (SCRAs). Each evolution of the pharmacology has proven to be far more unpredictable, dangerous and addictive than herbal cannabis, with SCRAs responsible for multiple deaths and thousands of hospitalisations in the last year alone.

SCRA addiction is a growing epidemic among homeless people, in part due to its low price and ease of availability. Until the Government’s Psychoactive Substances Act or ‘legal highs ban’ came into effect in May 2016, it was sold over the counter at head shops, with brand names such as ‘Spice’ and ‘Black Mamba’, providing a cheap and legal alternative to cannabis. But while criminalising SCRAs appears to have cut down use among the general population, it has done little to restrict access for vulnerable groups, such as the homeless.

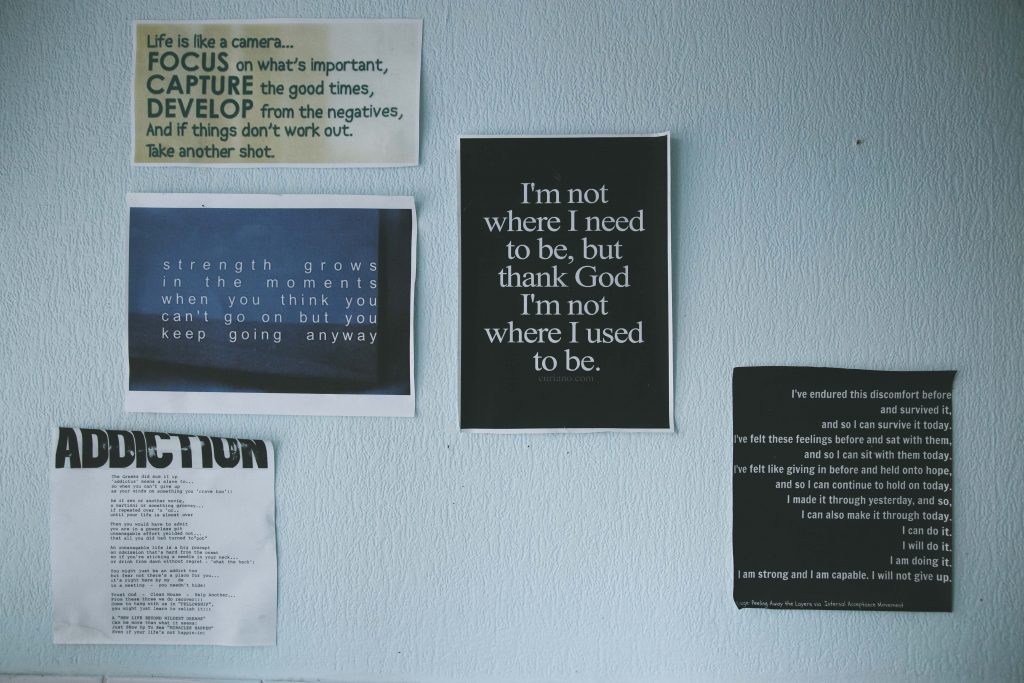

On the other side of Southend, Lewis, 19, and Chris, 20 are trying to put their lives back together at HARP’s halfway house in a white semi-detached Victorian house. Until they found the Restart programme, they were both on the streets, dealing with a number of issues, but addiction to Spice was sending them on an escalating downward spiral. The pair are among only a handful of people known by HARP to be in recovery, and they’re eager to share their experiences of Spice in the hope that others avoid what they’ve gone through.

“[When I first smoked Spice] outside college, I thought ‘What’s this? I’ve got to have more,’” Lewis says. “I went to the shop later that day to buy more and from there I started to lose everything: my relationship, family members, education…”

He pauses, and hangs his head in his hands.

“With weed and other drugs, I’ve never felt anything close to Spice. I just had to have more.”

No nationwide statistics exist for SCRA addiction among homeless people. However, Andrew, a Substance Misuse Co-ordinator at HARP, who works with Chris and Lewis, says it’s now a bigger problem for people under 23 than crack and heroin – but frustratingly little is known about its harmful effects or how to devise effective treatment strategies.

Chris and Lewis described withdrawal symptoms after an hour without smoking that could include sickness, mood swings or shaking. Their need to get more of the drug at whatever cost put them on the streets. From that point onwards, their usage went up dramatically as they struggled to deal with the pressures and insecurity of being homeless.

Both were alarmed by the psychological effects of smoking high quantities of Spice they saw having on other homeless users, such as walking around like dogs, barking or hallucinating wildly. Lewis developed psychosis and attempted to jump from the roof of a car park.

“My worst experience was when I smoked four grams alone in a dark room,” Chris says. “I was seeing demons and they were touching me. It was terrifying.”

Despite a number of highly-publicised deaths, many people still see Spice as no more dangerous than herbal cannabis. Harry Sumnall, Professor in Substance Use at the Public Health Institute, suggests this simply isn’t the case. The high can be similar, but the pharmacology and toxicology of SCRAs means they should be considered a totally different drugs.

“We’re seeing a more diverse range of [harmful] effects and perhaps some serious conditions as a result of SCRAs like Spice that you wouldn’t see with herbal cannabis,” Harry explains.

People are primarily hospitalised due to changes in heart rate or panic attacks, which can occur with herbal cannabis too. But Spice is mostly responsible for more serious complications like heart attacks, strokes, and damage to the kidneys or liver. Psychiatric symptoms including psychosis, paranoia and hallucination are much more likely from synthetic cannabinoids than herbal cannabis.

Both data and research on novel psychoactive substances (NPS), such as SCRAs are deficient. Yet, statistics from Public Health England for 2015/16 show that across the general population, numbers of people who sought treatment for issues related to SCRAs, such as support with addiction, rose significantly.

The Government’s ‘legal highs ban’ was intended to combat this, but Chris and Lewis explain that criminalisation has failed to reduce the availability of SCRAs to homeless people. They argue instead that the ban has increased the amount of adulteration to batches of SCRAs on the streets.

“From research into traditional illegal drugs, we know that always happens: availability rarely changes but the price increases and both the impurity and harmfulness of the product increases as well,” Harry explains.

However, due to the unregulated and unconventional nature of the NPS market, inconsistencies were rife, even before the ban, Harry explains. “Uncertainties about what’s in the Spice products is not a new problem, it has always been an issue,” he says. “Even with the branded, nicely-packaged products, it was never really clear to most users what they were smoking. Our analysis has shown that the actual content of those products varied enormously, even within particular named brands. You could never really know what the dose or potency was, but those risks might have increased with the introduction of the criminal market.”

Lewis and Chris are happy to have put their experiences with Spice behind them and are slowly trying to rebuild their lives. But for the homeless community in Southend, and across the UK, government drug policy appears to be doing little to halt the growing problem of NPS addiction.

“Historically, we’ve seen that policies based on restricting supply have little impact on groups like the homeless, who have pre-existing relationships with and are targeted by dealers,” Harry says. “There’s a high profit margin, the ingredients for NPS are readily available and they are easy to make, which makes suppressing supply a challenge. Experience suggests the NPS ban won’t have much impact on high-risk populations, like the homeless, but then that has always been the way with drug laws.”

Alex King is a journalist, he writes regularly for Huck Magazine and Little White Lies. Tweets @AlexKing89

All photos by Theo McInnes.