On Monday, VolteFace will publish our first policy paper, The Tide Effect, in collaboration with the Adam Smith Institute.

The Tide Effect presents cannabis law reform as an irrepressible force, sweeping towards the UK from the USA and Canada. In advance of The Tide Effect, author Boris Starling digs into the history that has led to cannabis being so harmfully misunderstood, and which underpins the way it is treated by govenrment policy today.

‘Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.’ – George Santayana, The Life of Reason: Or The Phases of Human Progress, 1906.

The history of cannabis in both the UK and the US is not a glorious one. It is a tale of racism, government crackdowns, the wilful confusion of public health with public order, and a fundamental dishonesty in refusing to consider cannabis under the same terms as tobacco and alcohol. And for ‘history’, also read ‘present.’ For cannabis, it seems that the more things change the more they stay the same.

Every society values, enshrines, legalises and protects certain dangerous but pleasurable pursuits as part of its culture. Prime among such pursuits in Western countries have long been smoking tobacco and drinking alcohol (apart from the brief and disastrous attempts at prohibition in 1920s America) – ‘long’ in this case meaning several centuries, which in turn means they predate modern health standards and legal structures. Fags and booze are seen as integral to our collective historical narrative, whether portrayed in positive terms (Sir Walter Raleigh bringing tobacco back from the New World) or negative (Hogarth’s ‘Gin Lane’ paintings of working-class squalor and degradation.)

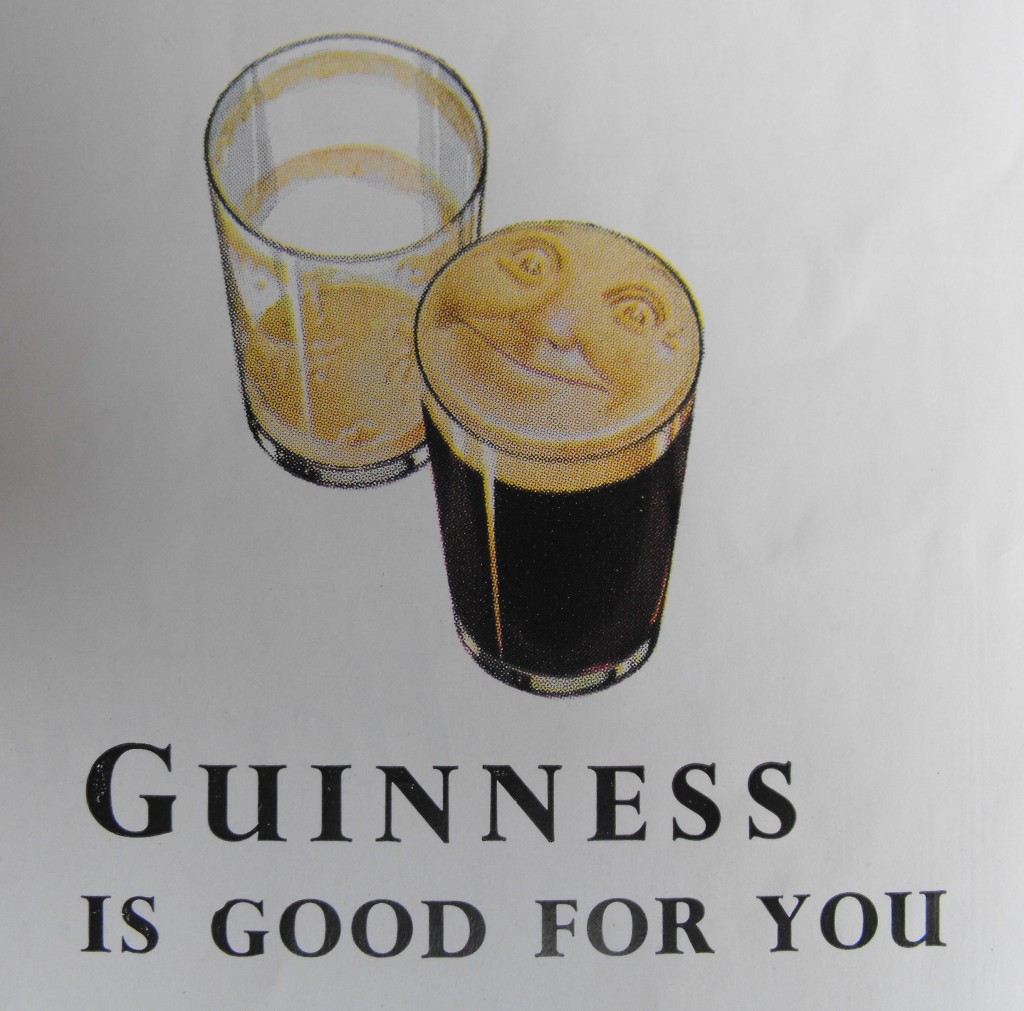

Even as the dangers of tobacco and alcohol have become more apparent in recent decades – no advertiser would get away with ‘Guinness is good for you’ nowadays, for example – the consumption of the substances themselves has still been seen as a health problem in need of management rather than a social threat in need of restriction. Quite the opposite, in fact. The well-funded tobacco and alcohol lobbies managed for several decades to advertise their products as befitting an aspirational lifestyle, be it Marlboro Man squinting into a distant horizon of canyons and buttes or Bacardi Rum evoking a tropical idyll where it’s always rum o’clock.

That such images were at odds with the lifestyles of 99.99% of smokers and drinkers was neither here nor there. Cigarettes and drink were explicitly marketed in the same way as items of sophistication such as perfumes and sports cars: a chance to transform your life, or at least your self-image.

In contrast, cannabis was always seen as the immigrants’ drug. In the UK, those immigrants were mainly West Indians coming to Britain after the Second World War. ‘Unless something can be done to stem the ‘invasion’ of unemployed coloured men (mostly British subjects) from Africa and the British West Indies,’ wrote F. W. Thornton, the head of New Scotland Yard’s Drugs Branch, in 1951, ‘we shall in a very short space of time be faced in this country with a serious hashish smoking problem… [these people] are of little use in our labour market and…. associate with lower class white girls, drink, peddle hashish cigarettes and generally present a problem to the police.’

Of course, what that statement doesn’t say is even more interesting than what it does. Cannabis was not merely an issue in and of itself, but as a touchstone for other, wider fears of social change and racial tension which only continued and grew throughout the Sixties and Seventies. Those fears still persist today, as indeed does the use of cannabis as a proxy political talisman.

A politician’s view on whether and to what extent the drug should be legalised can act as a useful shorthand for their general outlook. Those who position themselves as pro-legalisation are often seen as liberally enlightened or dangerously irresponsible, depending on where the viewer is standing: those against are sensibly conservative or blindly reactionary, again depending.

In the US, the immigrants in question were Mexican rather than West Indian and the connection between them and cannabis began long before the Second World War: in the first two decades of the 20th century, in fact, when cannabis was widely seen as something smoked by the immigrant labourers whose cheap wages were undercutting small farmers. California passed a law in 1915 outlawing ‘preparations of hemp or loco weed’, and several other states in the west and Midwest followed suit over the next decade or so. ‘All Mexicans are crazy,’ said a Texan senator during a 1919 debate on the subject, ‘and this stuff [cannabis] is what makes them crazy.’ Again, we can see the clear and simple power of association. These people are a threat – these people smoke cannabis – therefore cannabis is a threat.

Isaac Newton’s Third Law of motion (‘for every action there must be an equal and opposite reaction’) applies to the field of crime and punishment just as much as it does to physics. Cannabis’ increasing popularity – it was soon seen as a black drug as much as a Mexican one, especially once the jazz musicians of Chicago and Harlem began to reference the herb in their songs – invited a backlash from law enforcement as comprehensive as it was inevitable.

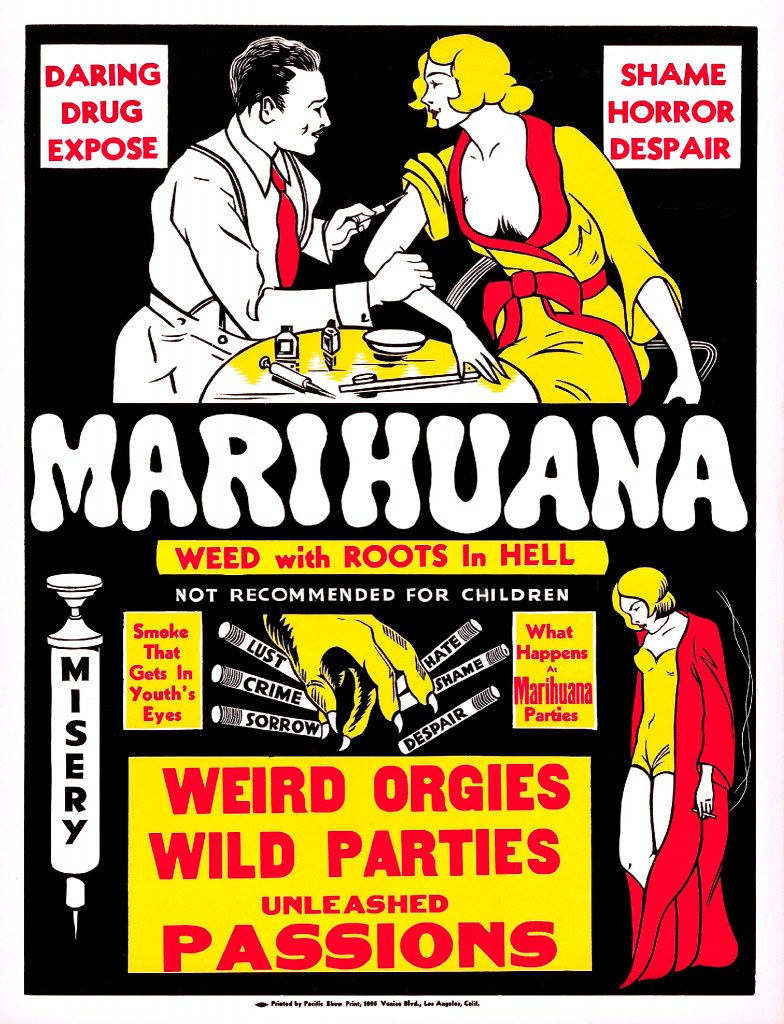

The Federal Bureau of Narcotics (FBN) was established in 1930 under the leadership of the relentless Harry J. Anslinger. In an atmosphere whipped up by the yellow journalism of William Randolph Hearst’s newspapers – ‘marihuana [sic] influences Negroes to look at white people in the eye, step on white men’s shadows and look at a white woman twice’ ran a syndicated editorial column in 1934 – Anslinger traded on lurid stories of ‘reefer madness’, gruesome killings and interracial sex to gain ever greater powers and arrest thousands of people each year for possessing even the most innocuous amounts of cannabis.

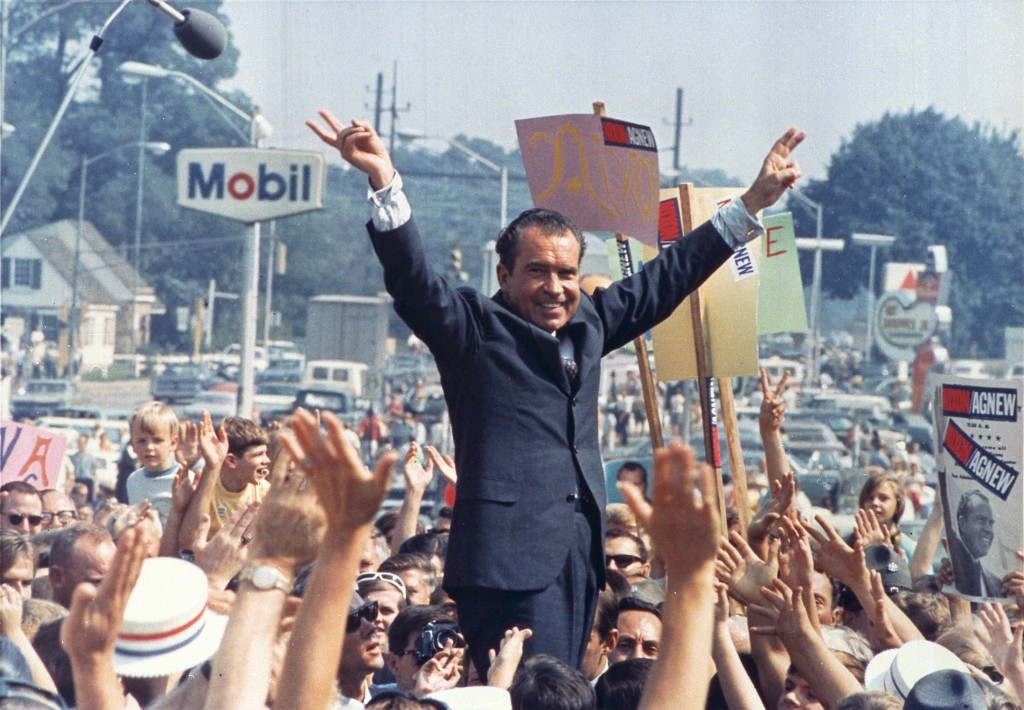

By the time Anslinger stepped down as FBN director in 1962, he had firmly established the narrative that cannabis was the drug of the opponent – that is to say, of anyone who pitted themselves against the government, be they students, hippies, Vietnam protestors and so on. ‘[Richard Nixon] had two enemies,’ said Watergate conspirator John Ehrlichman: ‘the anti-war left and black people … we couldn’t make it illegal to be either against the war or black, but by getting the public to associate the hippies with marijuana, and blacks with heroin, and then criminalising both heavily, we could disrupt those communities. We could arrest their leaders, raid their homes, break up their meetings, and vilify them night after night on the evening news. Did we know we were lying about the drugs? Of course we did.’

The racist aspect of law enforcement policies on cannabis continues to this day on both sides of the Atlantic. As revealed by Release in their 2013 report, The Numbers in Black and White: Ethnic Disparities in the Policing and Prosecution of Drug Offences in England and Wales, in the UK, seven out of 1,000 white people are searched for drugs. Corresponding figures for mixed race, Asians and black people are 14, 18 and 45: in other words, Asians are two and a half times more likely to be searched than white people, and black people are six and a half times more likely. When it comes to warnings and charges, the ratios are slightly different but the trend remains the same: black people are three times more likely to be warned than white people and five times more likely to be charged.

These ratios tie in to more general patterns of law enforcement: in particular, to the fact that a black person is 13 times more likely to receive a prison sentence than a white person. The racial aspects of policing and of cannabis policy are not separate issues: they are interlinked, and will continue to be so for as long as cannabis remains a matter for law enforcement rather than public health.

A similar situation exists in the US, highlighted by no less an authority than President Barack Obama himself. ‘Middle-class kids don’t get locked up for smoking pot, and poor kids do. And African-American kids and Latino kids are more likely to be poor and less likely to have the resources and the support to avoid unduly harsh penalties. We should not be locking up kids or individual users for long stretches of jail time when some of the folks who are writing those laws have probably done the same thing…. it’s important for society not to have a situation in which a large portion of people have at one time or another broken the law and only a select few get punished.’

Unlike cannabis, alcohol and tobacco are not freighted with such incendiary racial associations: they have not only (almost) always been legal, but have also been widely used by the dominant social and economic classes. If tobacco and alcohol were suddenly to appear nowadays, would they be banned? Probably.

Certainly by any standard definition – ‘a substance which has a physiological effect when ingested or otherwise introduced into the body’, for example – alcohol and tobacco are ‘drugs’ every bit as much as cannabis is. That most people don’t think of them as such shows the extent to which they have become socially embedded, and by extension the effect to which language matters, no matter how unthinkingly we use it.

Unlike tobacco and alcohol, cannabis will continue to be seen as a ‘drug’, with all the negative connotations of that word, until it’s legalised and regulated: but to legalise and regulate it in the first place requires a major neuro-linguistic switch in the minds of both policymakers and public opinion. It is a proper Catch-22.

Boris Starling is a British novelist, screenwriter and newspaper columnist. Tweets @vodkaboris