These are three short extracts from a book in progress by Adam Gee entitled ‘When Sparks Fly – the creative rewards of openness and generosity’. Each chapter focuses on a different discipline – this first chapter centres on writing/publishing.

WITH A LITTLE HELP FROM MY FRIEND

– Allen Ginsberg

He had an unfortunate combination of interests – drugs and guns. Oh, and writing. That’s how, off his face, he came to shoot his beloved wife in the face, bang in the middle of the forehead. And be in Tangier, one step ahead of the law, stoned at his typewriter. He taps away, gets to the end of a sheet, it floats to the floor, he winds in a new one, taps away, floats. Day after day, week after week, the sea of paper gradually rose round his feet till Ginsberg came to his aid.

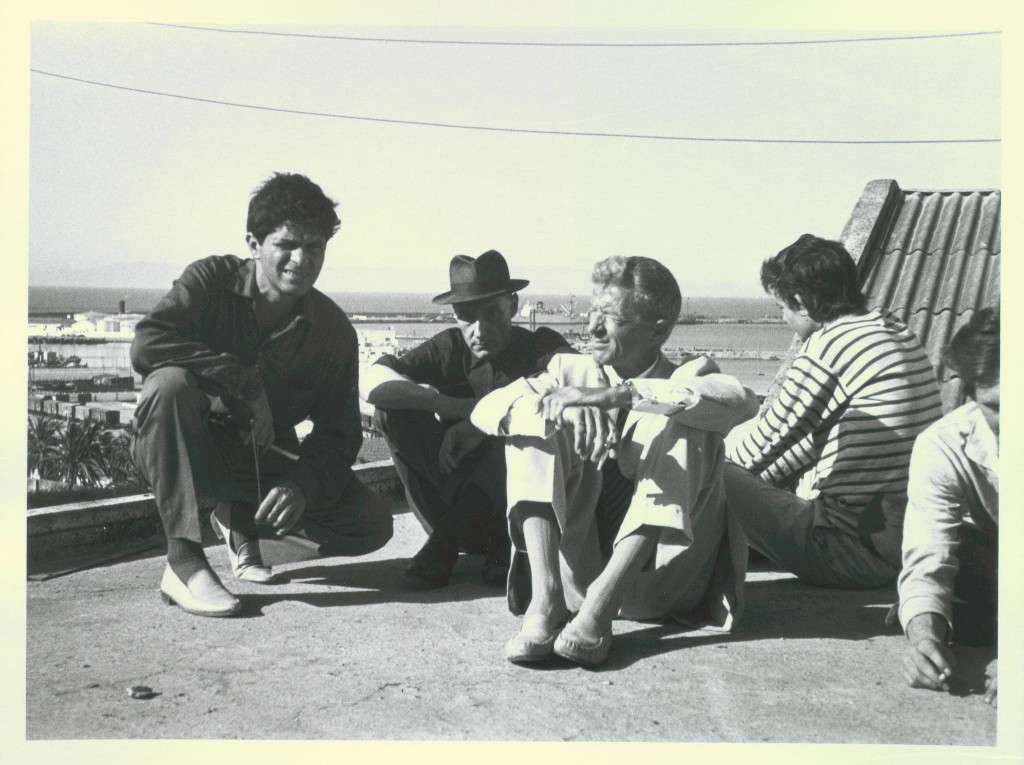

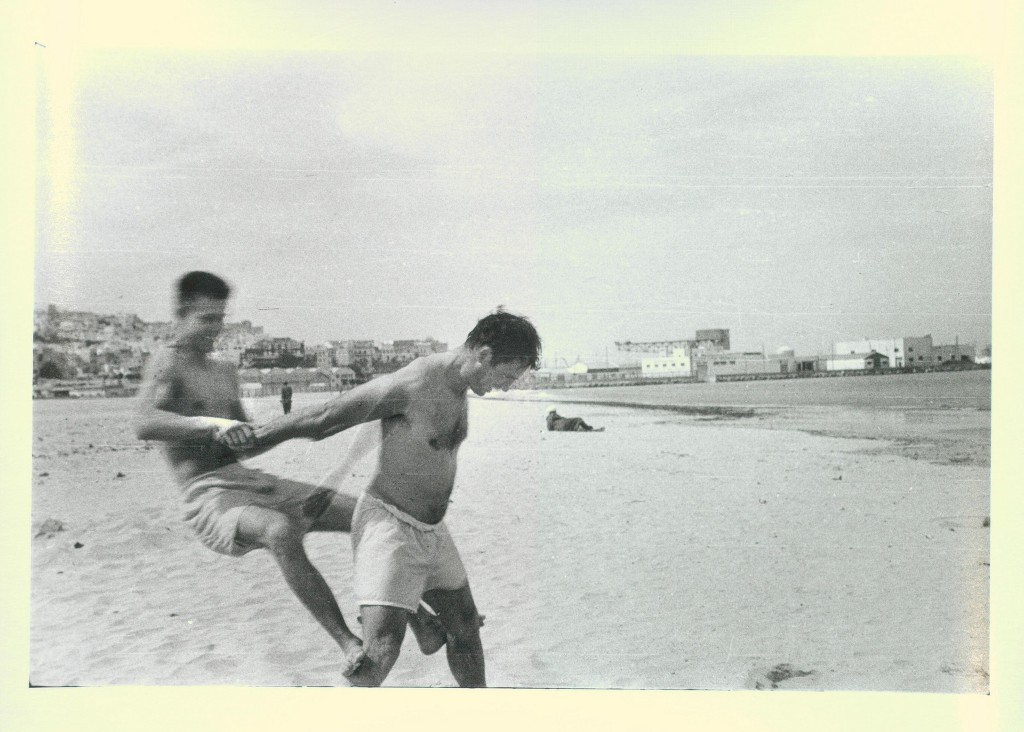

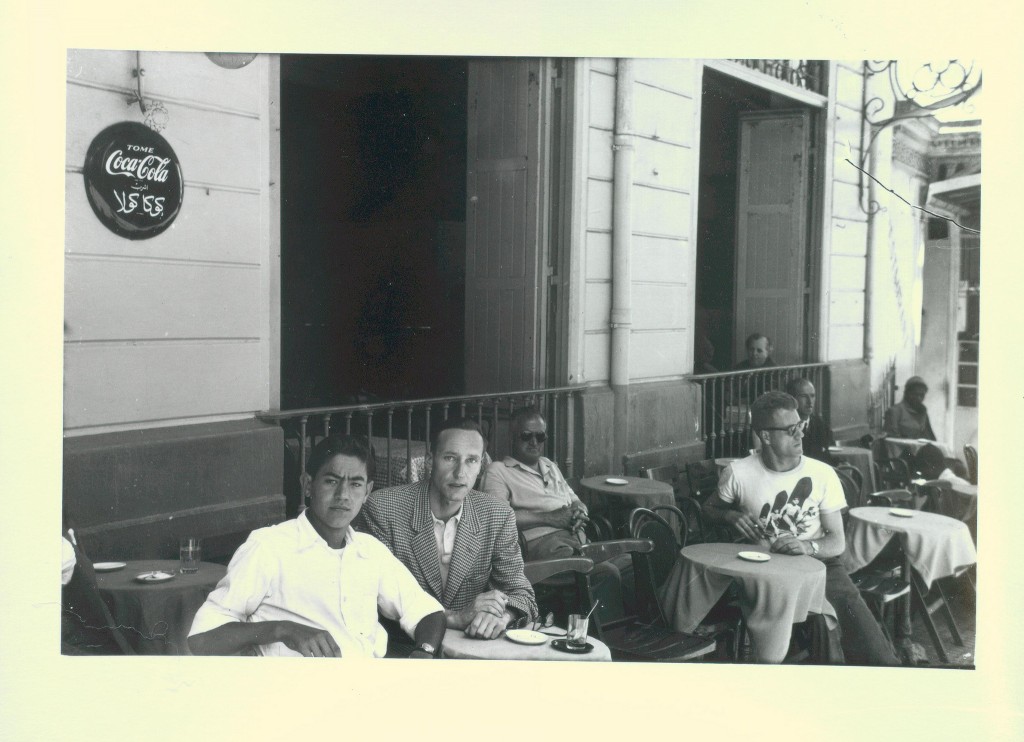

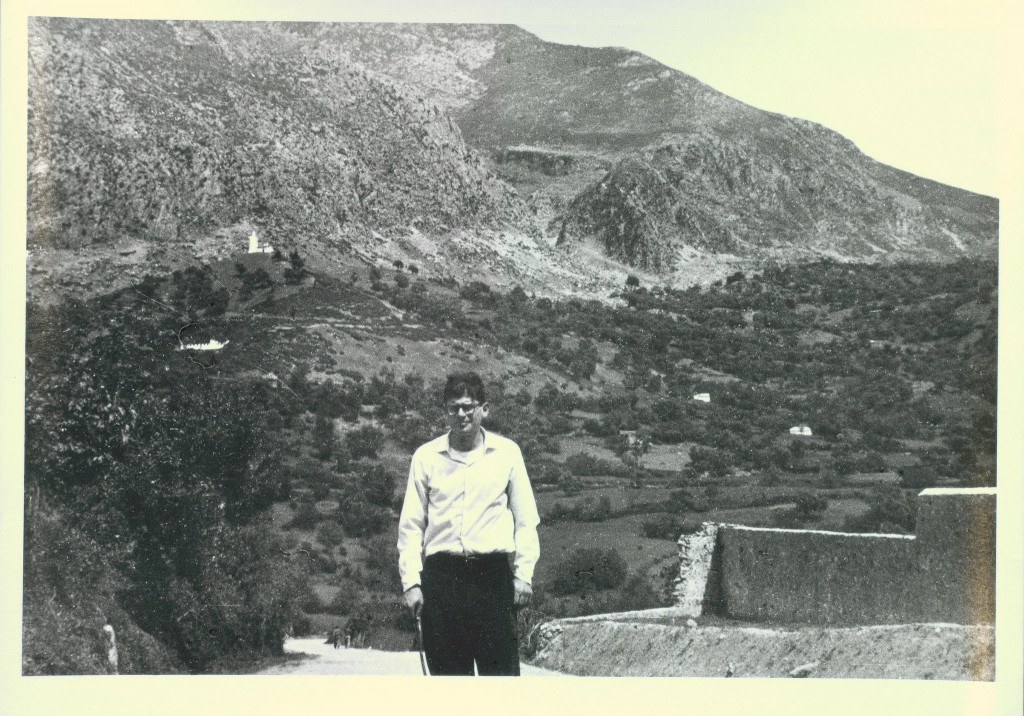

Allen Ginsberg was always good at keeping the gang together. He organised a working holiday in Tangier, gathering for the trip fellow Beat writers Jack Kerouac, Gregory Corso, Alan Ansen and Peter Orlovsky. Ginsberg had funded the whole enterprise himself by signing on as a ship storekeeper on a vessel bound for the Arctic Circle. So they pitch up in March 1957 (having lost Corso along the way and Kerouac bailing early on them) at William Burroughs’ place in the Hotel Villa Muniria, pick all his paper off the floor and start trying to get it into some kind of sense, a publishable order. We’re talking months not days here, a really generous commitment of time and brain-power, a very hands-on form of editing to transform powerful but disparate writings into a coherent whole. Just over two years later the rising tide of paper is published as Naked Lunch. Today it sits on the shelf labelled Modern Classics.

On his way out of Tangier Kerouac passed through Paris and left off some chapters of Naked Lunch with Maurice Girodias, who ran Olympia Press. Olympia was largely in the business of publishing ‘DBs’ (dirty books), although it occasionally hit the literary jackpot, more by luck than judgment (such as with Lolita and The Ginger Man). Girodias wasn’t too taken with the typescript, way too light on the dirty sexy stuff. Ginsberg, however, managed to persuade him to give it a go, taking advantage of the publicity erupting in the French press at just that moment about him and his fellow Beats (Ginsberg’s break-through poem, Howl, had just been the focus of an obscenity trial back in the States). The Olympia contract was lousy but Ginsberg persuaded Burroughs to go ahead and sign as something of a loss-leader. It proved a real headache for Burroughs further down the line but typifies Ginsberg’s values which lay firmly in the publication not the dough, in the outcome of getting the work in front of people over the income.

To some degree Jack Kerouac’s own modern classic, On The Road, also owes its presence on the shelf to Ginsberg’s openness and generosity. Kerouac had been schlepping the manuscript around for the best part of five years trying to get a publisher to take it on. With Kerouac close to giving up, Ginsberg took up the baton and, whenever closing one of his own book deals, would whip out On The Road and tell the publisher they really had to take on this great story. The reader at The Bobbs-Merrill Company found it “boring”; ACE Books thought it “unintelligible” but offered him some cash to write something a little more racy. That at least gave Kerouac enough to get back on the road.

It was Ginsberg who opened the door at ACE Books through his friendship with Carl Solomon, a budding writer he first encountered in the nuthouse. ACE sat on On The Road for some time before eventually getting cold feet, but this got the novel well and truly on the radar and in the end it landed Kerouac a professional agent. The book got picked up by Viking Press and published six years after it had been completed. And the rest is history.

Between 1950 and 1952 in particular, Ginsberg was actively engaged around New York trying to get his friends’ writing published. New Yorker journalist Jane Kramer’s experience of him in the late Sixties was “anyone asking Ginsberg then – and now – about his own work was likely to get a long and rapturous reply on the virtues of the whole group.” Ginsberg had been guided and mentored by fellow New Jersey poet William Carlos Williams (a contemporary of his father) as well as by Burroughs (twelve years his senior), Kerouac (four years older than him) and Corso (four years younger) and in some, not entirely conscious, way this was payback.

When City Lights published Howl Ginsberg’s vision was that it would herald a series of sister publications by friends, with poetry by the likes of Corso, Gary Snyder and Philip Whalen, and novel-length prose by Kerouac and perhaps Burroughs. After Howl came out Ginsberg took Corso, Kerouac and Orlovsky (the Tangier posse) out by bus to Rutherford, New Jersey to introduce them, in his characteristic connecting way, to the renowned poet William Carlos Williams. He wanted also to hand over an inscribed copy of Howl and Other Poems by way of thank-you for the introduction he had contributed to the volume and his consistent support.

Burroughs likewise had guided him and been something of a mentor at Columbia College, New York. Ginsberg first met him in 1945 as a sophomore and Burroughs gave him reading lists ranging from Mayan codices to Rimbaud, by way of Kafka, Yeats and Blake. Burroughs had taken a master’s degree in Anthropology at Harvard in the mid-Thirties. The next decade he was “just kind of observing things”, living modestly off family money. Shortly after Ginsberg met him, he became the core of a live-in literary hang-out-cum-salon in the Cragsmoor building on West 115th Street. Ginsberg and Kerouac introduced him to Joan Adams, who in due course he married – and eventually shot fatally in the forehead. Also living in this off-beat commune was Herbert Huncke and Kerouac. Ginsberg joined the merry throng in the Spring of ’45 after getting kicked out of Hamilton Hall, his Columbia hall of residence, for writing (an ironic) ‘Fuck the Jews’ in the dirt on the windows in a bizarre battle of wills with the Irish cleaning woman, a war of attrition over the cleaning which he lost.

Not only did Ginsberg rescue Naked Lunch from that North African floor in 1957, he also passed the manuscript of Junkie to Carl Solomon. The first draft of Burroughs’ Junkie had been contained in a series of letters to Ginsberg, giving a modern twist to the notion of the epistolary novel. Burroughs often lacked confidence in his writing – Ginsberg’s reassurance frequently served to unblock him and get the words flowing again.

– PART 2

Ginsberg’s openness included his attitude to drink and, even more so, to drugs. These formed part of his lifelong drive to achieve the kind of consciousness he had once experienced through the poetry of Blake. The intense vision he had that time in East Harlem (in the Summer of 1948) whilst chanting Blake’s Ah! Sun-flower over and over in his bedroom lasted days and marked the opening of his mind. He approached drugs in a spirit of experimentation and exploration, looking for a return to that place. In due course they got replaced by meditation. While he was travelling that route though, he did so with the exacting precision of a scientist, recording the sensations stage by stage. He did this when he first tried alcohol as a 16 year old, recording each step along the way to drunkenness. Likewise with the various hallucinogens he tested. It was Burroughs and Huncke who introduced him to drugs. He only ever once came anywhere near addiction – that was in what came to be known as the Beat Hotel on Paris’s Left Bank, where Burroughs’ and Corso’s heroin habits came close to infecting him. He was a demon with the ciggies but otherwise avoided the drug and drink death-traps that eventually took down many of his friends.

When a friend of his girlfriend (he was trying to ‘go straight’ at the time, October 1954) gave him some peyote to try, despite the demonic visions it conjured up out of the San Francisco fog, he had sufficient presence of mind to get down notes and those notes fed straight into Howl.

In May 1957 Ginsberg took a trip West to San Francisco. On his way he dropped by Menlo Park to take part in an experiment that was to have profound ramifications for American culture for over a decade. He volunteered to try out a psychedelic drug they were testing at Stanford – LSD-25. Ironically it turned out the whole thing was CIA-funded. The Agency was looking for an aid to interrogation, Ginsberg was after an aid to illumination. It wasn’t as good as masturbatory Blake but it ran a close second.

In the clinic where Ginsberg received his first dose of LSD worked an orderly with writing aspirations himself. His name was Ken Kesey and he began One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest within a year of Ginsberg’s introductory trip.

After attending a writers’ conference in Chile in January 1960 Ginsberg made his way to Peru in search of a psychedelic near-death experience through yage, the ‘death vine’ Burroughs had tried out and documented in the early 50s. Ginsberg persisted through a series of terrifying sessions until he gained a true sense of the naturalness of death in the human condition, an insight which served him until his passing in New York in the Spring of 1997.

Ginsberg used a trip to India with Gary Snyder to sample the local narcotics at each stop along the way. He took the opportunity to visit an opium den and undertake a long anticipated experiment. He caught back up with Snyder in Kyoto, Japan in 1963. Snyder had long been a student and advocate of Eastern culture and religion and brought Ginsberg to Buddhist meditation practice. Having formal meditative training for the first time enabled him to grasp the essential role of the teacher. (In time he came to pass on the essentials of what he learned about meditation to his audiences, combining his poetry reading with meditation instruction and chanting.) The importance the figure of the Teacher came to have for him is evident in his death – he had his ashes split between three locations: the Shambhala Mountain Center, Colorado, because it was Chogyam Trungpa’s retreat, his first real guru; Jewel Heart Michigan, as Gelek Rinpoche was his teacher at the time he died; and his family plot in New Jersey to be by his father.

On his way home from Kyoto, Ginsberg wrote a poem, The Change, during his return train journey to Tokyo – it marked his shift from the partial insights of drug trips to the harder won transcendence of meditation. It also brought a new self-confidence in the form of a still broader openness – a willingness to share thoughts about drugs and death, homosexuality and politics, anything under the sun. Consequently he re-opened his bisexuality, enjoying a rich mix of sex with both genders.

– PART 3

Allen Ginsberg for me is the gold standard, the exemplar par excellence of the creative person who works with openness and generosity, and through that catalyses their own creativity and that of others.

What’s the difference between a person like Ginsberg and a philanthropist? or patron? or salon owner? or impressario? Sometimes not a lot but always something, something significant. The distinction can be fine but there are some key characteristics which distinguish Ginsberg types from these others – perhaps most importantly, nurturing and championing their peers (as opposed to their juniors). The mentoring of younger creatives is generous but common, in some ways par for the course, and often is framed in terms of relative power. It takes a certain self-confidence to promote your peers and an insight to realise that is not to your detriment.

When Ginsberg led his band of merry men to Tangier to grapple with Burrough’s papers he was 30 years of age, the writer he was nurturing was 43; Ginsberg had only just been published, Burroughs was a published author with a Harvard degree.

I’ve no intention of reducing the shared characteristics of Ginsberg and the other protagonists of When Sparks Fly to some slightly forced model to help guide people through how best to work in an open and generous way which catalyses creativity. I want rather to highlight attitudes and ways of behaving which creatives have successfully used in the past to the benefit of both their own and others’ creativity. I’m not arguing these are always conscious – it doesn’t really matter provided they are authentic.

The stories here, although primarily from the realm of arts and media, extend to other areas like science and business to emphasise that creativity cuts across all manner of disciplines.

I have deliberately focused on people from a largely pre-digital age. (Only the final chapter interfaces with the digital.) This is because there’s a half-truth in circulation which says these characteristics of Openness and Generosity are born of open source software development and such online collaboration. That’s true to some degree but I want to show how this way of working has much deeper roots and plenty of precedent for success.

All that has changed in the Digital Age is that it’s even easier to work in this way than ever. Networked digital technology has sharing, collaboration and connecting in its essence.

During my decade working at Channel 4, the UK broadcaster with a specific public service remit to innovate, I have increasingly come across people (predominantly outside the organisation – some directly related as suppliers and the like, others more obliquely connected) who are using the kind of approaches Ginsberg grew into. They range from besuited, seemingly establishment types to tattooed street Herberts but their ways of working and being are much the same.

Ginsberg may be perceived or dismissed as a benign cuddly, bearded type so I have set him beside Tony Wilson [Chapter 2] who’s familiar epithet around the home city he championed so loyally was “wanker”. It’s not about being ‘nice’. Ego plays a key role in a number of these stories. It’s about having a genuine love of connecting ideas and people, and making creative things happen…

Adam Gee is an award-winning London-based interactive media and TV producer and commissioner. He has won over 80 international awards for his productions – including four British Academy Awards (BAFTA), an Emmy, three Royal Television Society (RTS) Awards, a Design Council Millennium Award and the Grand Award at the New York International Film & Television Festival.