The World Health Organisation (WHO) decides this week whether to further examine if cannabis should remain on the international list of most restricted substances, signalling a potential change in the international law on cannabis.

This is a welcoming move in the wake of a recent media frenzy around the Charlotte Caldwell case in Britain and the unprecedented support for medical cannabis treatments for her son suffering from epilepsy and other patients, as well as the announcement by the French Health Minister this summer about their intent to regulate medical cannabis.

While many states are moving towards regulation, a major deterrent – and indeed an often cited argument by officials – are the UN restrictions on reforming policy. Although an incremental step in dismantling prohibition, the WHO rescheduling decision could be a litmus test for future policy reactions – and thus accelerate national advocacy efforts.

Last week at the 40th session of the Expert Committee on Drug Dependence (ECDD) of the WHO discussed if cannabis (including the plant and resin, as well as cannabis extract and tinctures, THC and its isomers) should be further reviewed later in the year in the process of potentially moving the substance to schedules that require less control.

Cannabis is currently both on Schedule I and Schedule IV, an additional measure reserved for drugs of “particularly dangerous properties.” Committee is set to announce the decision later this week or early next here.

According to a long-time patient activist Michael Krawitz with the Veterans for Medical Cannabis Access, the current review process of looking at science for evidence represents in fact a “normal, routine process – that was just never done,” at any point in the history of prohibition.

Namely, when cannabis was put on the list of controlled substances in 1961, policy-makers “concerned with the health and welfare of mankind” were establishing the system of the War on Drugs – a reality of prohibition many are living today.

However, so-called evidence used to declare cannabis as a dangerous substance with no medical value, was in fact based on racial and cultural stereotypes and prejudice that informed the policy of War on Drugs since its inception. In other words, decision-makers were not seriously looking into science, but rather resorted to fear-mongering and cultivating misinformation.

As the scheduling in question formed a legal basis for prohibition of cannabis that ensued in 1960s in almost all countries in the world, implications of this decision could be significant for patients, advocates and users globally. Rescheduling could potentially ease access to cannabis research, and could take the pressure off from countries willing to experiment with cannabis policy.

Break-down of the review process

As mentioned above, tThe cannabis plant and cannabis resin are listed both on Schedule I and Schedule IV — the two most restrictive categories.

Schedules are essentially lists that divide substances into varying degrees of addiction potential and medical benefits. There are four schedules created by the Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs in 1962, which applies to cannabis.

In essence however, there is only one prohibition schedule – Schedule IV, for substances that should essentially be locked away, implying the strictest amount of control due to its “particularly dangerous properties.” (Schedule I contains substances that have a high potential for abuse and addiction, while Schedule II is for substances that have a slight addictive potential, and Schedule III for substances which have more potential for medical use.).

The CND and UNODC, as well as WHO have the power to request a scientific review of particular substances contained on the various drug schedules, from the Expert Committee on Drug Dependence housed under the WHO mandate to evaluate substances for international control based on scientific evidence.

This review was initiated by the CND resolution 52/5 of 2009, as well as a request by the INCB, UN’s watchdog of the drug control treaties tasked with the ability to interpret them.

Review itself is a two-phase process (containing a pre-review phase and a critical review phase) of collecting scientific evidence and scholarship on the substance and organising hearings of experts and stakeholders that are then summarised in a closed meeting of the ECDD into a recommendation on what the CND should do, as the final outcome document. Should ECDD decide to proceed to the the critical review phase which will be published later this week or early next, final decision is set for November.

At the hearing on June 4th in Geneva, Dr. Gilles Forte, Secretary of ECDD recognised there are high expectations from the Expert Committee from all the parties involved and reaffirmed they will follow their mandate of producing a judgement based on scientific evidence.

Dr. Mariângela Simão of the WHO of the WHO acknowledged certain Member States’ fear this process would “trigger softening of the drug control system,” and responded in spite that this would be an evidence-based decision-making process that puts health and wellbeing at its core.

Dr. Simão’s point echoes a growing discord started at UNGASS 2016 between Member States on how drug policy should be conducted.

UN General Assembly Special Session (UNGASS) was the first opportunity in 18 years for the drug reform movement and a number of high-level state officials to focus their efforts and advocate for regulation and a public health approach, which essentially broke the long-standing consensus on the politics of prohibition.

A part from policy experimentation on cannabis springing up in many corners of the world, this changing paradigm includes decriminalisation of drug users, as well as instituting policies of harm reduction that focus on the health needs of drug users and consider socio-economic dimensions of addiction.

Along with several states in the US, one of the frontrunners of this wave is certainly Uruguay which instituted a measure in 2013 to regulate marijuana for medical and non-medical (recreational) use. When this measure was announced, the International Narcotics Control Board (INCB), watchdog of the drug control system, reprimanded US and Uruguay in saying these laws pose “grave dangers to public health.”

UNGASS essentially introduced a rift between staunchly prohibitionist countries such as Russia, China and Pakistan and those more friendlier to reform such as the EU, Switzerland and Uruguay. With the reform movement of policy experimentations well on its way in many countries, tensions of non-compliance are growing within the drug control system. This is a particularly worrying fact for the UN agencies which care fundamentally about respecting international law.

One of the ways in which the treaties could be updated for the purposes of 21. century was presented by Prof. David Bewley-Taylor of the Transnational Institute as a result of a discussion of scholars and state officials. Namely, a viable and elegant option for resolving treaty tensions would be to establish an inter se agreement between several reform-oriented countries in which they would essentially reform the drug treaties amongst themselves, while simultaneously respecting that remaining countries’ obligations towards the treaties and ensuring there new policies would not cause a spillover to Member States who are not parties to the inter se agreement.

New Hopes for the International Narcotics Control Board

There is tremendous gap between policy-makers in Vienna and the reality on the ground. So far in eyes of many activists, the INCB have been the bad guys. However, now that the science is being put back into policy by the WHO – an actor external to the UNODC, it is quite possible this process could be the catalyst for the legwork of educating decision-makers about reality and stakes on the ground.

According to M. Krawitz, while the agency used to bark at countries in violation of the treaties – like in the case of Uruguay, there is a sense they are moving away from it and trying to figure out what to do next.

In fact, this May 7th, the INCB organised a first ever civil society hearing of 10 representatives who shared their on-ground experience about the use of cannabis for medical and non-medical purposes. Institutionally, it would make sense for the INCB to plug into what could essentially be a re-definition of its scope.

This effort – made in cooperation with the Vienna Committee of Non-Government Organisations (VNGOC) – comes as a result of a call voiced in various UN fora of ensuring a meaningful participation of civil society in the policy-making process.

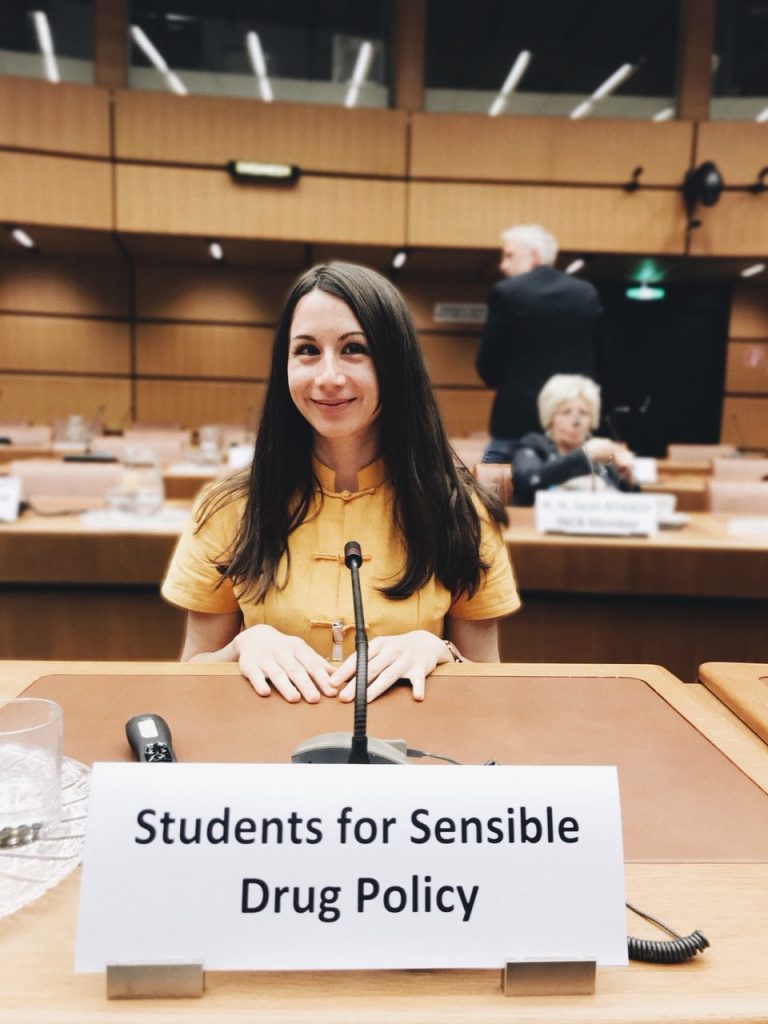

At the hearing, representatives came from both the reform and prohibition sides. According to a young activist representing Students for Sensible Drug Policy Elena Yaneva, those unfamiliar with the topic might be inclined to weight the arguments of the prohibitionists as viable because they use ambiguous terms and confusion tactics to engage in what is essentially a manipulative recycling of decades-old arguments – of cannabis as a gateway drug, misrepresentation or fear-mongering around addiction potential or a complete lack of medical benefits of cannabis.

Nevertheless, it is safe to report “nothing reasonable or up to date” was presented by the prohibitionist side. “There are not so many activists working on this level who can also be present in the sessions” she added, expressing that more people could get involved.

Yaneva presented on hemp as an economically viable and sustainable alternative and called for further research. According to Yaneva, we have been looking at cannabis sativa for too long as an illegal drug, or just a drug, while the reality is that hemp – low-THC content species of the plant – has immense potential. Namely, hemp’s bark fibres and seeds can be used for over 50,000 products as building materials, industrial products, and in hygiene, paper, food, and textile industry, while the plant itself is very sustainable due to low carbon footprint and significant potential for innovation, for example as insulation material.

Promoting hemp as a sustainable alternative complements the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), and as such is a viable advocating point at the UN. While SDGs are UN’s biggest effort to date, some “policies actually run counter to its SDGs”, such as the case with drug policy.

On top of that, Yaneva added the current regulatory framework has made research extremely difficult – while the need to know more about the plant is stronger than ever.

Barriers to research

One of the strongest arguments for removing cannabis from Schedule IV are precisely barriers to research, cited by almost all reform advocates – and with a good reason.

When cannabis was put on this list of controlled substances in 1961, no committee made a scientific review of the substance. Policy-makers back then were led by the racism and fear-mongering around substances. Although the drug control system established options for medical and scientific research, significant regulatory and financial hurdles prevented research from being done.

One of these relates to how a substance is handled. Schedule IV proscribes substances to be under “direct supervision and control of the Party” (Member State). In practice, this meant all cannabis research had to go through the national agency in charge, which – combined with an unfavourable cultural climate and stigma around cannabis – resulted in a research moratorium.

Moreover, although numerous studies on cannabis were launched when Vietnam veterans started recognising its therapeutic values in 1960s, United States government outlawed research in 1976. Prof. Raphael Mechoulam who identified THC in 1963 with his team at the University of Jerusalem was alone in this field of research for decades. Today, majority of the 1,500 scientific studies published on the subject were produced after 2010, showing promising results for chronic pain, nausea, epilepsy, autoimmune and inflammatory diseases, etc.

According to M. Krawitz, current scheduling is what has prevented us from having gold standard research (controlled, double-blind studies), often precisely cited as what is needed to change policy. Rescheduling could be a way out of the enchanted circle.

Moreover, Schedule IV also prescribes that unique paperwork be filed for each patient who want to obtain a medical cannabis licence. According to a French physician and activist Bertrand Lebeau, having to ask the relevant state authority for each patient is one of “worst and most debilitating provisions.” In France for example, this means a medical cannabis patient has to acquire signed documents from five ministries(!) in order to get a licence for treatment.

On the other hand, there is a worry that if there is a green light for pharmaceutical medical cannabis, but the plant is not rescheduled, the question of access will make it impossible for many patients to get the treatment they need. In Uruguay for example, a bottle of 10ml of CBD costs around $70, a five day’s worth supply for a severe condition. According to Dr. Raquel Peyraube, this is the reason 57% Uruguayan patients with chronic pain or other conditions self-medicate by using cannabis flower. According to German cannabis expert Dr. Franjo Grotenhermen, the flower still remains the cheaper option.

Implications

Removing cannabis from the Schedule IV – the most restrictive one, alone would have a pretty profound impact, if we take into account that this provision served as a legal basis and a soft obligation for Member States to prohibit cannabis nationally. Although an incremental step in dismantling an inadequate system, it could essentially open a clearer pathway for regulation by Member states around the world.

For example, long-standing argument of the United States administration is that removing cannabis from their federal Schedule 1 would be in violation of the UN treaties, and is thus impossible. While rescheduling does not do away with this restriction completely because cannabis is both on the international schedule and in the text of the convention, something being a more recent decision could take precedent in international law, as well as – most importantly – urge a change of policy of the compliance watchdog, the INCB.

In light of the fact that cannabis use has been around for thousands of years, the words of a French physician that we live in “the worst century for drug policy” ring strong. If the international community is to have any legitimacy as a global governing entity, it will need to perform tremendous work of correcting its wrongs. And it is on patients and activists to spread the word and do what they can to get policy back to reality.

Sara Velimirović is a Sciences Po Paris graduate covering global drug policy, former board member for Students for Sensible Drug Policy. Tweets @SaraVelimirovic