The inexorable momentum towards cannabis legalisation has taken hold across the globe. New, courageous policies are emerging in all corners of the earth – from Uruguay to Canada, from Ireland to Germany, a wave of positive reforms are being passed or pondered over by policymakers.

However, Julian Buchanan suggests that, for all the positive propulsion of the global legalisation movement, it may well pay dividends to take our time and work out the best way to legalise, lest we repeat the mistakes of the past.

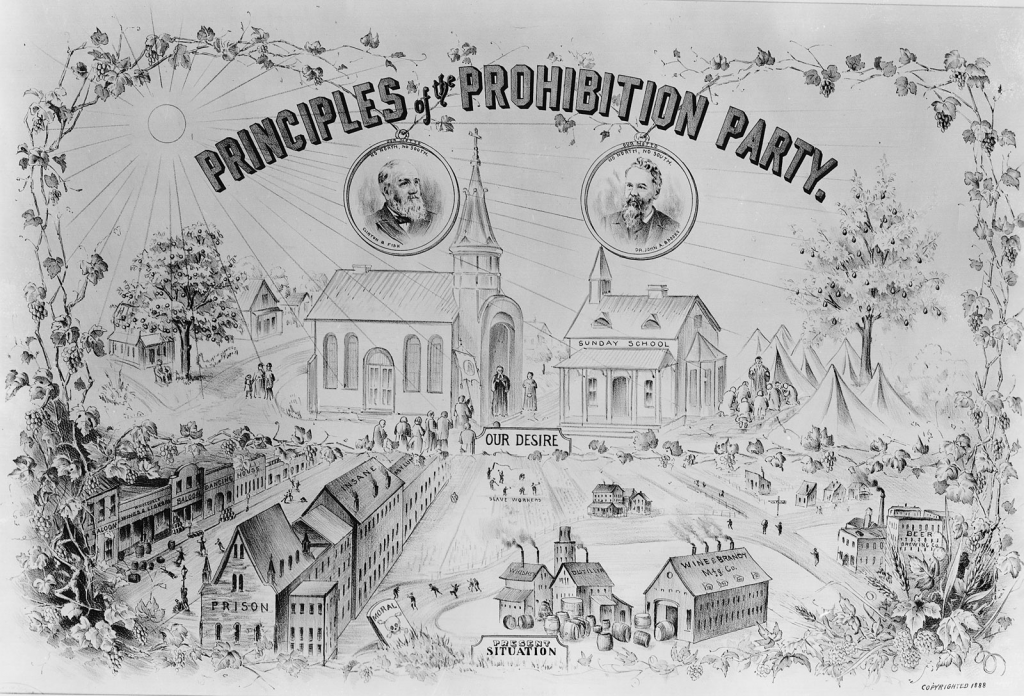

Yes – clearly cannabis should be legal, but, more fundamentally, we need to tackle the damages of drug prohibition which has led to an irrational and unscientific bifurcation of drugs. An archaic system that favours, promotes and culturally embeds the use of some drugs, while fiercely policing, prohibiting and punishing the use of other drugs.

The 1961 UN Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs, and the drug laws it spawned in signatory countries, are deeply flawed, misinformed and misguided – they are an abuse of human rights and civil liberties. The realisation of this dreadful mistake, and the momentum to end this draconian regime, has gathered pace in recent years.

While the US Government has been a driving force defending and upholding drug prohibition, it is ironically the US citizens who are challenging the regime by voting en masse to legalise cannabis. To many this is seen as a major step towards bringing an end to prohibition. However, I would question how inviting cannabis to enjoy the privileges of other favoured drugs (alcohol, caffeine and tobacco) will tackle the wider and fundamental problem of drug prohibition.

Signs in Amsterdam, indicating smoking cannabis and drinking alcohol are prohibited. (Wikimedia Commons)

Ironically, the legalisation of cannabis could actually bolster prohibition.

The global and (somewhat) united drug reform movement could be undermined as an inadvertent consequence of privileging cannabis by granting it legal status. This then helps further ‘divide and rule’, by maintaining and consolidating this process of bifurcation.

No doubt (and understandably so, after the decades of oppression cannabis users have suffered) legalisation of their drug of choice will be met with a celebration of the new found freedoms and privileges, but possibly also by a lack of interest to fight to end the iniquitous system of drug prohibition. The result: a system that privileges and punishes users of different drugs. Furthermore, it could give rise to a new momentum against ‘drugs’ or ‘hard drugs’ – as freshly liberated cannabis users might redefine themselves as ‘herbalists’, ‘sensible recreational users’ or people who use ‘soft’ drugs.

I want to see cannabis legalised and sensibly (rather than strictly) regulated – in a way that avoids the oppression inherent in prohibition, and in a way that avoids the commercial exploitation we’ve seen in the tobacco and alcohol industries. However, this is not something we should do for one or two selected substances, while maintaining and upholding prohibition against other substances. I’m an abolitionist, I want to see the end of drug prohibition and I want all drugs legalised and sensibly regulated – there is no place for law enforcement and prohibition, personal drug consumption is not an issue per se, and if ever it does become a problem, it is a social and health issue, not a matter for the police. We have, essentially, a world drug policy problem not a world drug problem.

UN Secretary-General Dag Hammarskjöld in front of the General Assembly building (1950s) (Wikimedia Commons)

Selectively privileging particular drugs based upon their popularity, to join alcohol, caffeine and tobacco as commercial products, is not the way forward, it’s simply an extension of the principles of prohibition. Granting pardons for particular drugs is a dangerous and uncertain pathway for drug reform.

Instead, we should challenge the very foundations of prohibition, and fight for the decriminalisation of every drug as a first step towards a comprehensive process to abolition. Once this is achieved we will urgently engage in that complex process: to explore how best to legalise and regulate all drugs.

A version of this article was originally published on Julian Buchanan’s blog

Read Julian Buchanan on the legacy of New Zealand’s much hailed drug regulation