Two new reports, released to mark the beginning of the 59th session of the Commission on Narcotic Drugs in Vienna this week, have once again laid bare the harms caused by prohibition and the need to radically change the way we look at drug policy in the build up to UNGASS 2016.

Strictly speaking of course, these aren’t actually new reports at all, but rather second editions of older studies, updated with even more damning evidence and statistics then their previous incarnations. The first, A Quiet Revolution: Drug Decriminalisation Across the Globe by Release, is a new version of a report which was originally released in July 2012 and has since been cited by a wide range of organisations and agencies, including the World Health Organisation, the office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, and the Global Commission on Drug Policy.

The fact that a new edition was necessary really says it all. Four years ago it was clear that there was a global trend towards decriminalisation, and in the intervening years that trend has been reinforced by a number of new countries making their own moves away from a criminal justice response to drug use and possession. With UNGASS just over a month away, the need to drive home this fact in the face of reluctance from those in power – to put harm reduction, human rights, and decriminalisation at the heart of the Outcome Document – could not be clearer, or more urgent.

Niamh Eastwood, the Executive Director of Release, says:

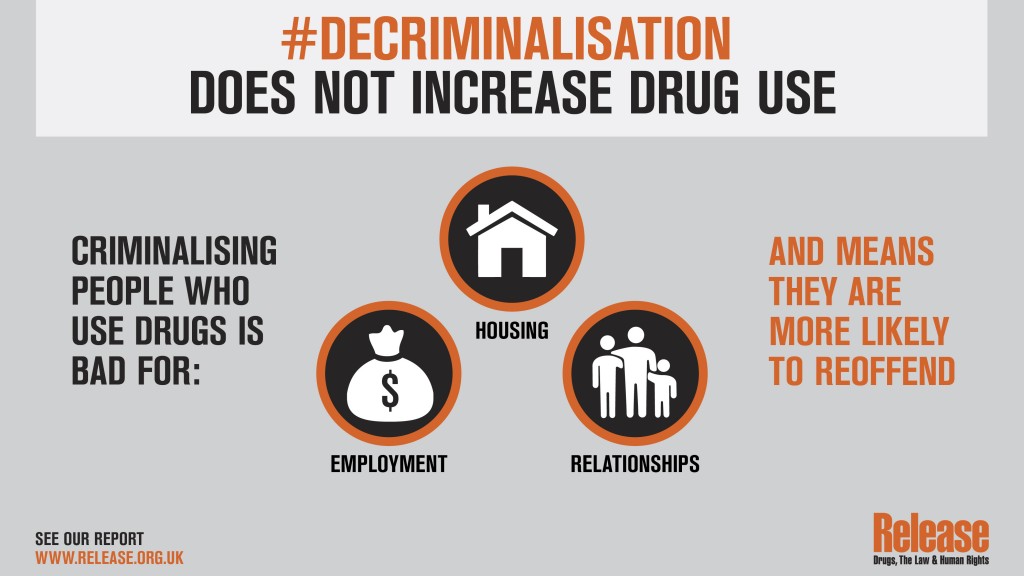

“Governments can no longer ignore the irrefutable evidence – ending the needless criminalisation of people who use drugs brings tremendously positive outcomes for society as a whole. In England and Wales 70,000-80,000 people are criminalised annually for simple possession, despite the UK government admitting in 2014 the futility of this approach, noting it doesn’t impact on use levels. Never has drug law reform been more pressing.”

That evidence, laid out by the report, draws on the experiences of over 25 jurisdictions from around the world that have decriminalised drug use. Key findings include massively reduced rates of HIV transmission and fewer drug-related deaths in Portugal, improved education, housing, and employment opportunities for people who use drugs in Australia, and savings to the state of California of over $1 billion in ten years.

The key finding though is that whilst decriminalisation cannot be considered a panacea for all of the problems associated with drug use and drug policy, and does not exist in a neat, one-size-fits-all model that can be applied globally – every country analysed by the report has its own nuanced approach to the issue – none of the doomsday predictions espoused by opponents of reform have come true, anywhere. There has been no opening of ‘Pandora’s Box’.

The second major report released (or updated) to coincide with CND comes from the Count The Costs initiative. The Alternative World Drug Report looks at international drug conventions in the context of the UN’s three founding pillars, and in particular Article 1 of the UN Charter – ‘to maintain peace and security.’ Its conclusion, that the current interpretation of the UN’s drug control system is ‘fatally undermining’ the very core of the UN, should provide serious food for thought for those gathered in Vienna this week and New York next month.

Over its 192 pages, the newly updated report takes an in-depth look at the costs of waging a worldwide war on drugs, and the possible alternatives to this punitive approach, including decriminalisation and legal regulation. Its key findings are as damning an indictment of the prohibitionary method as you are likely to see, and include the following. That the war on drugs:

• has created an illegal market worth $320 billion a year, serving a customer base of 250 million;

• has wasted billions of dollars, which could be better spent elsewhere;

• undermines peace and security in 1 in 3 UN member states;

• undermines development where drugs are produced and trafficked;

• undermines human rights through law enforcement;

• threatens public health, spreading disease and death;

• harms, rather than protects, children and young people;

• destroys the environment; and

• promotes stigma and discrimination.

The report doesn’t just stop at pointing out the harms though. It recognises that the UN Office on Drugs and Crime has acknowledged these terrible consequences of the drug war but shrugged them off as merely “unintended consequences”, or little more than collateral damage which in their eyes is necessary on the path to a drug free world. Crucially. the Count The Costs report demonstrates with stunning clarity the extent to which alternatives punitive drug policy are producing far better outcomes for everyone involved.

A Count the Costs spokesperson said:

“It is a tragic irony that the institution founded after the Second World War to uphold global peace, has waged an unwinnable drug war for over half a century. In doing so it is fatally undermining peace and security, development, and human rights – the “three pillars” of the UN, and its raison d’être. In effect, the UN drug control system has become a war machine, and in the process the UN effectively violates its own founding charter based upon maintaining world peace.

“Our updated report shows that the UN drug control system has created a money making opportunity for criminals so vast that drug cartels have become a threat to global security. And the militarised drug war response to this problem has only made matters worse. As an organisation pledged to promote peace, its member states must end the UN’s longstanding global drug war and explore the alternatives.”

NGOs around the globe will not let world leaders resume the status quo at UNGASS next month (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

Overall, there is little in these reports that can truly be considered groundbreaking or new. The conclusions drawn have been made and argued about for years, but the release of these two reports now, as we enter the final stages of preparations for UNGASS 2016, can be seen as part of a concerted effort by international NGOs and civil society to make sure that the issues highlighted are not swept under the carpet. UNGASS could be a once in a lifetime chance to reform drug policy for the better, and you can be sure that world leaders will not be permitted to rest on their laurels, regardless of the outcome.

Deej Sullivan is a freelance writer focused on drug policy reform. Tweets @sullivandeej