As we attempt to get our respective New Years resolutions in motion, Slate have shared a history of psychedelics, detailing their use as a therapeutic tool for squashing vices and healing depression.

Author Don Lattin opens proceedings with an account of Arthur King, who had submitted himself to LSD-based treatment for the alcoholism that had threatened his livelihood as a father of three:

This was not a normal psychotherapy session. During his 12-hour experience, designed to help stop his destructive drinking habit, King sat on the edge of the bed and looked at the photo of his son that he’d brought. Suddenly, the child became alive in the picture, which initially frightened him. Then King noticed that a lick of his son’s hair was out of place, so he stroked the photo, putting the errant strands back in place. His fear vanished.

Later, Unger held out a small vase with a single red rose. King looked at the flower, which seemed to be opening and closing, as though it were breathing. At one point, Unger asked him whether he’d like to go out to a bar and have a few drinks. King didn’t say anything but was shocked when the rose suddenly turned black and dropped dead before his eyes. He never picked up another drink.

The treatment proved an instant success, at least with King, whom Lattin lists as merely one of the ‘thousands of research subjects who were given LSD, psilocybin, and mescaline as therapeutic tools in the 1950s and 1960s, often with government support and with promising results.’

Research into psychedelic based therapy was essentially halted in the 1970s, and only recently, Lattin explains, has it re-emerged:

This research is only now gathering momentum again in a new wave of U.S. clinical trials into other drugs with psychedelic properties. In recent years, university administrators, government regulatory agencies, and private donors have begun giving the stamp of approval and the money needed for new and expanding research into the use of MDMA, also known as ecstasy, and psilocybin, the active ingredient in magic mushrooms.

In 2017, for instance, the Heffter Research Institute and the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies, two organizations leading the psychedelic psychotherapy revolution, will begin a final round of government-approved clinical trials in which hundreds of new patients with post-traumatic stress disorder, depression, and severe anxiety will undergo therapy sessions fueled by MDMA and psilocybin.

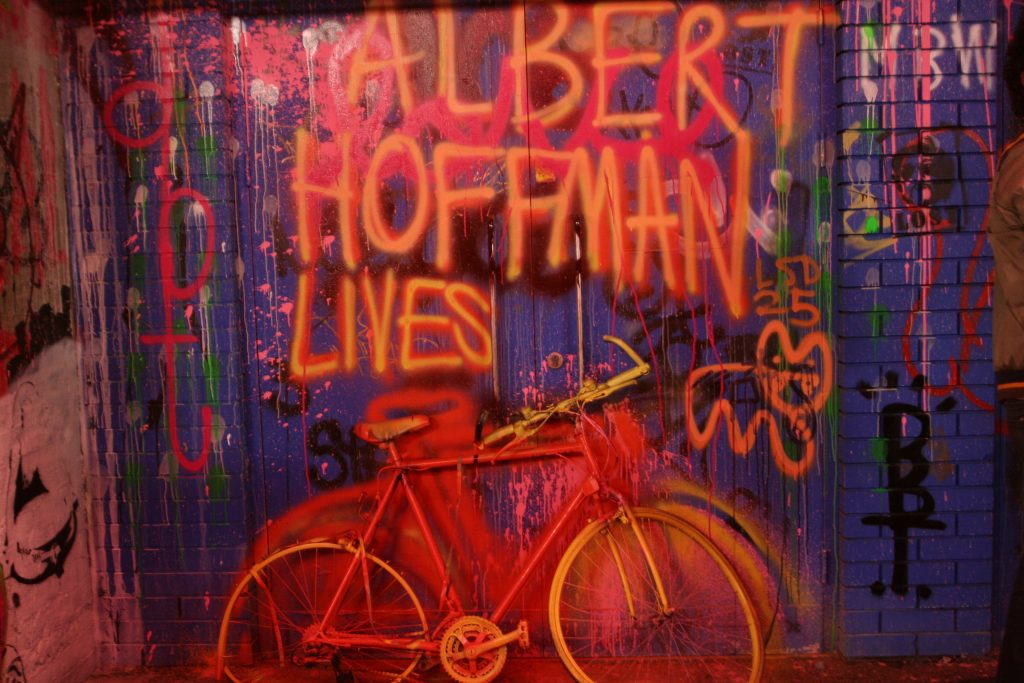

Lattin’s timeline zigzags backwards, in a typically trippy fashion, to the discovery of LSD by Swiss Chemist Albert Hoffman in 1943.

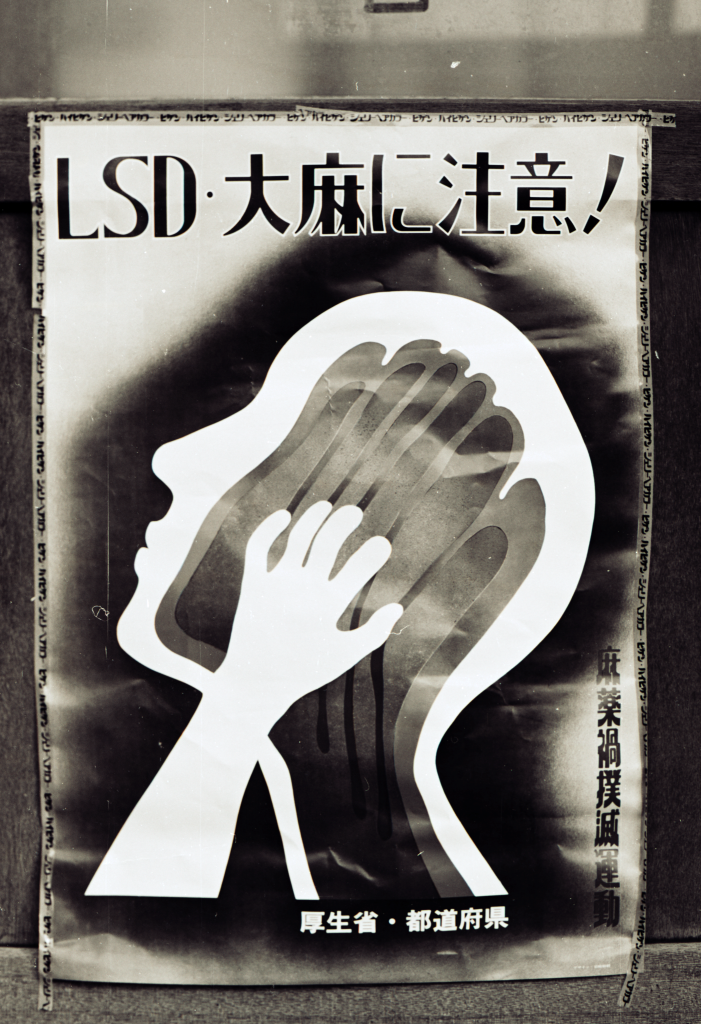

Psychedelics, our author recalls, have a now not-so-secret history of involvement with the US military, who conducted ‘tests to see whether LSD could be used as a truth serum or possibly be sprayed on enemy troops as a kind of weapon of mass distraction.’

However, in spite of their discrete weaponisation, curious healthcare professionals had been ‘conducting more socially beneficial experiments in laboratories and medical offices around the world.’

Meanwhile, brain scientists and psychotherapists were conducting more socially beneficial experiments in laboratories and medical offices around the world. Through the 1950s and 1960s, more than 1,000 research papers were written about LSD, psilocybin, and other psychedelic drugs. Some 40,000 subjects were given these mind-expanding agents, and great progress was made in the understanding of how they might help people suffering from depression, alcoholism, and the psychospiritual distress that often comes with the diagnosis of a life-threatening illness.

The baby boomers experienced these therapeutic benefits firsthand, as psychedelics would become synonymous with the counterculture movement of the mid-1960s:

A charismatic Harvard University psychologist named Timothy Leary reinvented himself as the “high priest” of the psychedelic counterculture. In California, a promising novelist named Ken Kesey gathered a Dionysian troupe of Merry Pranksters and put on a series of huge parties called acid tests, where revelers dosed themselves and danced to a new band called the Grateful Dead.

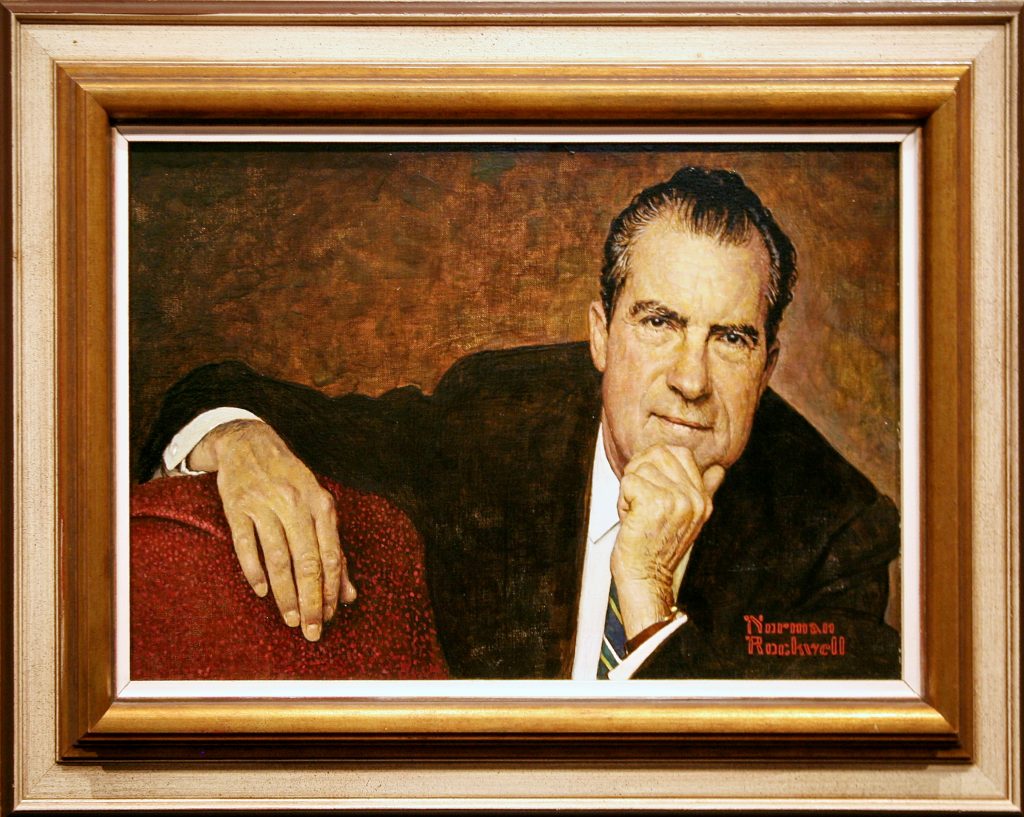

President Richard Nixon would famously go on to label Leary as “the most dangerous man in America”, and governments would thereafter maintain a strong, largely restrictive front against mind-expanding substances like LSD et al.

The crackdown on both recreational and therapeutic use of psychedelics was not simply a political reaction. It was part of a broader re-examination of the loose standards applied to all kinds of drug research in the 1950s and early 1960s. Today, there is a greater appreciation for the rights of patients and research subjects to be fully informed of the potential dangers and side effects of these compounds. LSD was and is an unpredictable tool when used carelessly—a fact that was discovered by both CIA operatives and counterculture crusaders.

Lattin maintains that the subsequent decades of drug prohibition have denied the public a great deal of invaluable research into the therapeutic potentialities of psychedelics, of which the medical community are only recently beginning to bring to light.

The article is a worthwhile primer on psychedelic research over the 20th century, and an engaging read to boot.

Words by Calum Armstrong. Tweets @vf_calum