This article was originally posted on Prison UK on 29/2/16 and has been republished with permission of the author.

Back in July 2014 I started blogging on the subject of so-called ‘legal highs’ in prison. Since then, the issue has come to dominate media coverage of our increasingly dysfunctional prison system.

Recently, we’ve seen Nick Hardwick, the former Chief Inspector of Prisons, warned of the threat posed by what are now being called ‘New Psychoactive Substances’ (NPS), variously known by generic names such as Black Mamba, K2 and Spice, as well as ‘herbal highs’. In addition, there is rarely an official report on any specific establishment that doesn’t flag up the rising tide of drug use.

The most recent warning reports about NPS – all published during February this year – have concerned HMP Cardiff (causing ‘horrific injuries’), HMP Dovegate (a ‘major contributing factor’ in riots), HMP Bristol (‘a huge and disruptive’ problem) and HMP Ranby (‘overwhelmed’, with fears for the prison’s stability and safety). However, in reality pretty much every prison in the UK now seems to be affected by what resembles an epidemic of drug abuse and violence.

The national and local media are also reporting on the crisis. There is a regular demand for ‘insider’ comment and over the past year or so I’ve been interviewed on Channel 4 News, BBC Newsnight, Radio 4, Radio 5 Live and have also been quoted in a feature in The Economist.

Of course, drugs are only part of a much wider problem in our jails. The prison drugs trade goes hand in hand with violence, bullying and self-harm. It may well be one factor fuelling the rising suicide rate. Based on my own observations in several different prisons, I believe that there is also a close correlation between the internal prison drug trade and the widespread availability of illicit mobile phones and SIM cards. Ironically, evidence of prisoner-on-prisoner violence inside jails occasionally leaks out through photos and videos made on these contraband mobiles.

‘…there is also a close correlation between the internal prison drug trade and the widespread availability of illicit mobile phones and SIM cards’

Unmonitored mobile communications are a vital tool in the smuggling business. Orders for ‘product’ can be placed with suppliers, gang members, family or associates back in the home community. Arrangements for mules and package drop-offs can be made. Prices in other jails can be compared and debtors who have been transferred when still owing money can be tracked and pressured to pay up – or can face punishment beatings on arrival in their new location. Debtors’ families can be intimidated or threatened unless their loved one’s debts are settled, either in cash or through being forced into smuggling drugs during visits.

Personally, I believe the ‘legal high’ problem began to escalate significantly during 2012. I first became aware of ‘Spice’ in a Cat-B prison when a Dutch lad, inside for drug dealing offences, started supplying pinches to other cons to mix with their regular rolling tobacco (‘burn’). I heard whispers about fresh deliveries coming in, although the route was never disclosed. Within a couple of months, use on our wing, and others across the prison, became commonplace.

These early substances seemed closer in effect to traditional cannabinoids. They relaxed the user and people just dozed off, although a few did vomit or shake. I recall having to support one mate who had been smoking the blended tobacco back to his cell and put him to bed before wing staff noticed the state he was in. He just slept it off, but complained of a stonking headache the next morning. I’m sorry to say that this didn’t discourage him and he was soon a regular ‘spice head’.

Gradually, other ‘brands’ of NPS arrived in prisons: Black Mamba, Amsterdam Gold, China White. Most were substances that mimicked the effect of cannabis, although others were closer to cocaine (methylphenidates). The latter substances tend to make users excited and sometimes aggressive. Both main types of high can fuel a sense of paranoia – something that is already rampant behind bars – and this can also lead to violent outbursts and other very disturbed behaviours.

One of the additional complications in prisons is that a significant number of inmates are already taking medication prescribed for depression or other mental health conditions. Some are on the methadone programme for heroin addicts, while others are using meds issued to others but sold or traded on the wing as a commodity. When you add NPS – the chemical composition of which is never certain – the result can be a dangerous form of Russian roulette. Will the impact be pleasant and relaxing, or will it induce vomiting, racing heart rates and even fits?

There have even been reports of prisoners being used as guinea pigs in crude chemical trials to see what effect a new batch of contraband substance is likely to deliver. Whether the participants are willing or are being bullied or threatened into testing these highs is difficult to determine, but evidence suggests that such practices are going on in certain establishments.

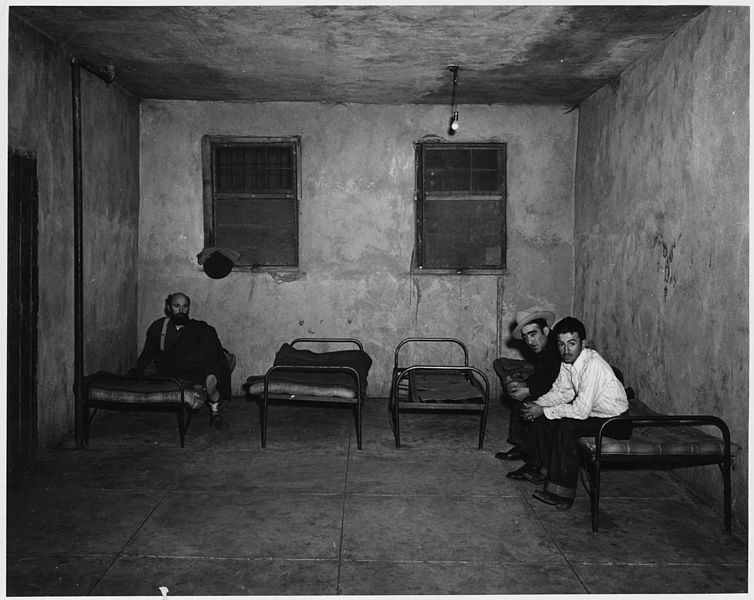

I have seen at first hand the negative impacts of widespread drug use in prison. Evening roll-checks in open prison where a long line of spaced-out cons staggered towards the office. Washrooms covered in vomit, WCs blocked, inmates passed out on the floor or heaving on their bunks. Ambulances – dubbed ‘mambulances’ – at the gate to pick up yet another prisoner who had been found lying on the floor in his own excrement and urine while having a fit.

The culture of violence is perhaps the worst aspect. A young, vulnerable lad being summoned to a cell far from the wing office to be systematically beaten by three much larger cons until he was battered, bloody and sobbing because he couldn’t pay his drug debts. I heard his pleas for mercy and then his screams. He was forced to clean up his own blood with his clothes before his tormentors kicked him out onto the wing, still deeply in debt and terrified of the next torture session he might face.

In open prison I have seen prisoners throwing away any chance of release on parole for years because they had run up drug debts they couldn’t pay. They then felt obliged for their own safety, or that of their families, to request a transfer back to a closed prison or even to abscond by running off.

Drugs – legal and illegal – get into our prisons because there is a growing demand. Life in many jails is now so grim, with restricted regimes, 23 hour bang up, little opportunity for work, education or exercise, that gambling with your health by smoking, sniffing or swallowing God knows what is considered a risk worth taking just to ‘get your head out between the bars’, as I’ve heard it called. My own estimate is that 40-50 percent of inmates were using by 2014, but more recent studies by leading academics working in this field suggest that as many as 60 percent of serving prisoners are likely to be misusing NPS or other drugs.

Moreover, the current absence of any Mandatory Drug Testing (MDT) for legal highs has made it almost impossible to prove that a prisoner has been using a contraband substance. Until and unless effective detection can be introduced for the wide range of chemical compounds (which change regularly), there is very limited deterrence in prison. At present, the usual disciplinary charge is possession of an unauthorised item, rather than a specific drugs offence.

Being a cog in the prison supply chain can be profitable, although nothing like as advantageous as it is for the barons who supply in bulk. Given the relative cheapness of legal substances on the street (sold as herbal incense), the returns can be substantial, while the actual risks of prosecution are very low.

Like all contraband, drugs of every kinds are smuggled into prisons through a wide range of routes. Newly arrived prisoners may be ‘packing’ or ‘plugging’ (concealing packages of drugs and other items in their rectums), while small wraps of drugs or pills can be passed over in the visits hall by family, friends or criminal associates. Even the nappies of visiting babies can be used. Attempts are also made to throw packages over high prison walls, while more recently there have been instances of small drones being used to breach prison security.

‘In open prison I have seen prisoners throwing away any chance of release on parole for years because they had run up drug debts they couldn’t pay. They then felt obliged for their own safety, or that of their families, to request a transfer back to a closed prison or even to abscond by running off’.

Staff shortages, poor morale on the frontline, too few security officers, not enough trained drugs dogs… all of these issues play contributory roles in producing an environment where the risks of smuggling contraband are considered worth taking – especially for the barons who get others to do most of the dirty work for them. Add in overcrowded wings populated by willing consumers and the stage is set for a perfect storm of drug-fuelled debt and violence, with the inevitable casualties. It’s also worth remembering that some of the worst, most violent prison riots in world history have occurred when rioting inmates have looted internal medical facilities after staff members have lost control.

Following my recent blog post on the subject of corruption among prison officers, I have received messages of support from both serving and ex-prison officers who resent the ‘rotten apples’ in their ranks, as well as predictable pressure from a few vocal individuals who would prefer me to ‘shut up’ and stop drawing attention to the issue, even though these serious problems are also being flagged by Nick Hardwick, former senior police officers and others who have first-hand experience of corruption in our prisons.

I am personally convinced that the sheer quantities of drugs and mobile phones currently available in our prisons would not be possible without some degree of involvement by individual members of staff. This includes a small minority of uniformed officers, but also some civilian workers and authorised contractors who enjoy freedom of access to specific prisons. In addition, almost any external consignment entering prison gates could conceal contraband items ready for internal contacts to retrieve and pass on.

With its usual sense of ‘urgency’ the government recently moved to criminalise the manufacture and sale of psychoactive substances (although not the mere possession) by means of the controversial Psychoactive Substance Act (2016) which will come into effect in April. However, there is doubt whether the new legislation will really reduce demand or consumption – whether in prison, where possession will become a new criminal offence – or out in the wider community. Judging by the failure of the so-called global war on drugs over decades, the prospects for success do not appear very positive. What is certain, however, is that there is no end in sight to the drug-fuelled crisis wreaking havoc across our prison system.

Stay tuned for an interview with Alex Cavendish of Prison UK next week on VolteFace