An edited version of this article was originally published on The Conversation under the title ‘More Americans are using cannabis – and view it as harmless’. We asked Ian to expand on what can be taken from this study when considering potential policy changes, and what its limitations are.

Surveys are fascinating and widely used from political polling to market research but they are not without their problems. Just ask any polling organisation that called the last general election results. Sample size and repetition of a survey doesn’t guarantee accuracy either, but we are all drawn to large samples and can think that annual surveys at least show trends. So when a study is published based on an annual survey of 596,500 people it captures attention.

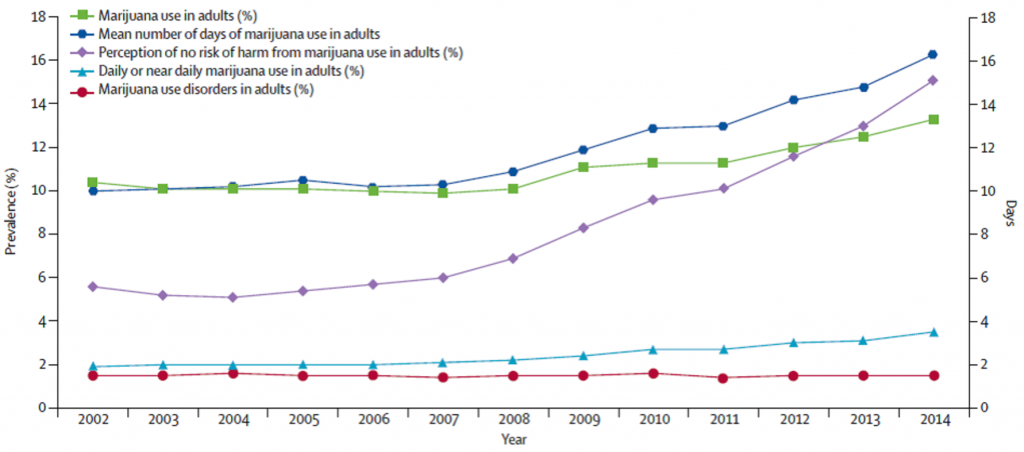

The study published in The Lancet Psychiatry reports a significant increase in the number of Americans using cannabis, rising from 21.9m in 2002 to 31.9m in 2014, representing 1000 new users a day. The number of regular users doubled over the same period to 8.4m. This coincides with an increasingly liberal approach to cannabis regulation in several US states. The authors also found that people perceived cannabis to be less harmful. This perception seems justified as problems related to cannabis use, such as dependency, remained stable during the study period.

These findings are not what you would expect when cannabis use becomes more popular and is thought to be increasingly potent. This study also contradicts another study, using data over a near identical time period, which found that disorders associated with cannabis use have doubled. So which one should we believe?

High risk groups not included

As with many studies The Lancet Psychiatry research has its limitations and the authors discuss these. A significant limitation is the survey data the authors rely on as it doesn’t include some of the most marginalised groups, such as the homeless or those in prison. These groups are more likely to use cannabis and develop problems, such as dependency.

A further limitation of the survey data is it excludes a high risk demographic group, those under the age of 18. This section of the population is more prone to developing cannabis problems than older people, for a variety of reasons. They are more likely to be novice and naïve in their use of the drug. They are also at a critical stage in their cognitive development which means use of any psychoactive drug including cannabis can impede their educational potential as well as increase the risk of developing mental health problems.

Also the authors did not include assessments for a range of mental health problems, this leaves an important part of the experience and consequences of cannabis use missing from the overall picture.

The absence of these groups and variables from the survey and analysis might account for the stable numbers of people with a cannabis dependency over the study period. So we need to be very cautious in the interpretation and use of these findings, particularly when considering how policy might be informed.

Self-reports

This data also relies on self-reporting, which can be problematic in all sorts of ways. Recall bias is one factor, for example could you recall what you did in detail last week ? last month ? Even if you try to answer as accurately as possible it is likely that you will forget something or perhaps fill in the gaps in your memory with your best guess. Asking about cannabis use has the extra problem of how honest you think you should be and if you do use cannabis how much the drug impedes accurate recall.

An inconvenient truth

It can be an inconvenient fact for those lobbying for a more liberal policy approach to cannabis that its use is risky for some. We know that a small number of people use the majority of cannabis consumed. This group is more likely to use a range of substances in addition to cannabis. They are also likely to have a range of additional social problems related to housing, education, employment and crime.

So far, the evidence suggests that those who dabble with cannabis are unlikely to suffer anything worse than feeling nauseous. Unfortunately, there are a small number of people who appear to develop more serious problems as a consequence of their cannabis use, such as mental health issues or dependency. Cannabis has also been implicated in other issues, including poorer educational achievement and doubling the risk of a car crash.

The way cannabis is ingested varies by country and culture. Although combining tobacco with cannabis is less popular in America it continues to be popular route of ingestion in the United Kingdom and other European countries. This represents one of the greatest risks for many users. For young new users this can be an introduction to tobacco which leads to dependency and all the harms caused by tobacco use.

Population experiments

An interesting contrast is emerging between the UK and the US. The US has increasingly adopted a more liberal policy approach to cannabis, and this research suggests it has been accompanied by increasing use of the drug. Meanwhile, the UK has continued to prohibit cannabis use – with the government claiming that falling use of the drug in the population justifies their policy position. Both countries are participating in a policy experiment on their populations. Unfortunately, neither country is collecting sufficiently detailed data to be able to draw any reliable conclusions. Both still have the opportunity to rectify this.

Ian Hamilton is a lecturer in mental health in the Department of Health Sciences at the University of York, with an interest in the relationship between substance use and mental health (Dual Diagnosis). Tweets@Ian_Hamilton_