In America in 1987 there was a government sponsored anti-drug campaign called ‘This Is Your Brain on Drugs’. It was based around a short public information film that showed a man cracking an egg (“this is your brain” he told viewers) into a hot frying pan (“this is drugs” he said, pointing at the pan). As the egg sizzles, he brings the pan up to the camera and says: “This is your brain on drugs. Any questions?”

One of the main questions people did have about this film was what drugs he was talking about. Was the frying pan an LSD tab? Was it a giant spliff, a bag of cocaine or heroin-filled syringe? No-one could work it out. But it didn’t matter. In the minds of the anti-drug campaigners, ‘drugs’ were in fact a singular entity, an amorphous bag of illegal ‘stuff’ that…fried your brain like an egg.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ub_a2t0ZfTs

Yet there was a time, not long ago, when ‘drug’ was not a word associated with death, villains and frying pans. Up until the late Victorian era, a drug was just a medicine you picked up from your local pharmacy or doctor to make you feel better. There were alcoholics, coke injectors (like the fictional sleuth Sherlock Holmes) and opium vendors, but no one labelled ‘drug addicts’ or ‘drug dealers’. There was no singular label for a substance that you took to get you high, let alone one that was illegal to buy.

But in a matter of three decades, the word drugs had taken on a whole new meaning. By 1900, for example, Arthur Conan Doyle had decided to scale-back his hero’s habit at a time, according to drug historian Mike Jay, when “the image of such drugs was changing fast”. The transformation of the word ‘drug’ is the subject of a new paper written by Professor Toby Seddon, head of Manchester University’s school of law, in which he points out that the journey of the word drug – from its innocent origins to its highly loaded meaning today – not only played a crucial role in the war on drugs, but could be the key to ending it.

Seddon begins Inventing Drugs: A Genealogy of a Regulatory Concept by taking a bird’s eye view of the word. He quotes the French philosopher Jacques Derrida, who said in 1989: “There are no drugs in nature…the concept of drugs is not a scientific concept, but is rather instituted on the basis of moral or political evaluation.”

He’s right. The modern meaning of ‘drugs’ is a social construct based on the fears and prejudices of people living over a century ago. Seddon admits early on: the purpose of his paper to “destabilise” this concept, to expose the root that is shackling us to an outdated system of laws. Otherwise he says, “moving beyond prohibition is impossible”.

Seddon has done some genealogical excavating and it’s interesting stuff. He traces the first use of the word ‘drug’ (as a substance taken to alter one’s psychic state), back to a New York physician called Lewis Mason in 1887 who told a conference on inebriety in London that some people had a “natural tendency to stimulating and narcotic drugs”. Suddenly the new drug buzzword is everywhere. It gets name-checked in medical journal reports on ether addiction in Berlin, opium intoxication in China, ganja use in Bengal and the smoking of bhang in Cairo. There are some positive mentions of the effects of ‘drugs’, but the word is usually linked to negative things: narcotic “enslavement”, the drugging of others and being a bad thing for the economy.

By the end of the nineteenth century, says Seddon, the new concept was thriving. “The notion of a drug no longer solely referred to a medicine but now had a secondary meaning, associated with vice and addiction, with criminality and danger, and with colonial and international trade interests.”

The final stage of the construction of the modern drug concept was a crucial one: the “decoupling” of one group of intoxicants – alcohol and tobacco – from the others, during and shortly after the First World War, culminating in the Dangerous Drug Act in 1920.

Why were some substances thrown in the bad, ‘drugs’ corner, while others were allowed to thrive in the light of day?

As it happens, Derrida has an interesting take on this one, again expressed during his magazine interview in 1989. He accepted that the division between alcohol and tobacco and ‘drugs’ was not down to matters of health. So he wondered, what do we hold against the ‘drug’ user? His answer: the act of inauthentic pleasure.

“Something we never, at least never to the same degree, hold against the alcoholic or the smoker: that he cuts himself off from the world, in exile from reality, far from objective reality and the real life of the city and the community; that he escapes into a world of simulacrum and fiction.

“We disapprove of his [the illicit drug user] taste for something like hallucinations…drugs make us lose any sense of true reality. In the end, it is always, I think, under this charge that the prohibition is declared. We do not object to the drug user’s pleasure per se, but we cannot abide the fact that his is a pleasure taken in an experience without truth.”

Derrida touches a nerve. But Seddon concludes that the main driver behind this “decoupling” was a more practical one: the targeting of substances being used by members of society deemed social deviants at the time, specifically ethnic minorities and the lower classes. Soon these were the substances that were to became known as ‘drugs’, whose buyers and sellers were soon to be transformed into criminals and over time jailed in their millions across America.

In reality, the clampdown on this new, corralled group of substances labelled ‘drugs’, became a clampdown on specific groups of people. Racism provided the momentum behind a new fervor for “anti-cocainism”: freed black slaves in the southern American states, once plied with cocaine to make them work longer, were chased down for taking the same substance, now an abhorrent ‘drug’, in their spare time. While white Americans got pissed on a booming alcohol industry, the authorities equated cocaine with “uppity southern blacks”, race riots and inter racial drug parties.

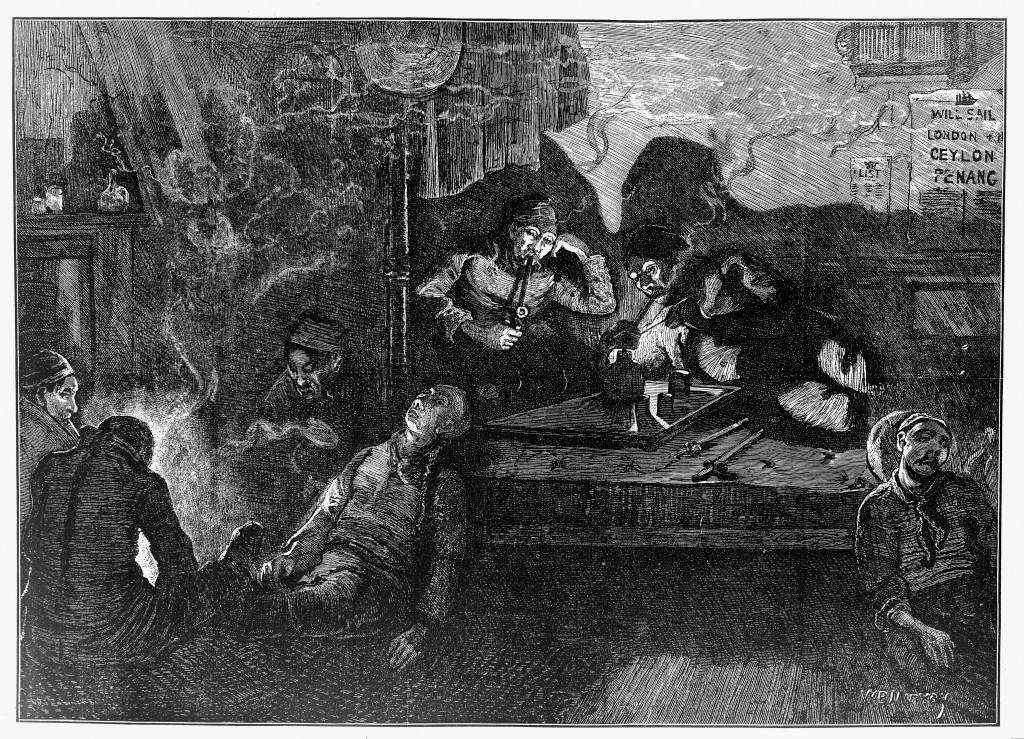

In San Francisco and London’s East End, the authorities saw opium as a narcotic weapon, used by Chinese men to corrupt white women. Portrayed as potions of the undesirables, opium and cocaine were soon consigned to the metaphorical and physical drug den. “The sustained connection of the consumption of particular psychoactive substances with disliked or feared minority groups was a key element in the final assembly of the drug concept,” says Seddon.

With the First World War over the focus on both sides of the Atlantic turned to defending society from internal threats. As Seddon describes in his paper: “Drugs, or more precisely the people who used them, were now seen as the ‘enemy within’. The creation of a raft of new drug laws in the first three decades of the twentieth century, banning heroin, opium, cocaine and cannabis, was seen as an apt solution to address the perceived dangers presented by social deviants and their drug taking. Alcohol and tobacco became big business, yet the substances marked ‘drugs’, were banished to a moral and legal dark side, all equally as bad, all leading down the same slippery slope to hell.

A clear line was drawn, between good and evil, black and white, drug and non-drug. While those who used ‘drugs’ were morally deviant, people who used alcohol and tobacco, while occasionally scarlet faced, riddled with gout and afflicted by lung and heart disease, were upstanding members of society. Lurid newspaper tales encouraged them to look down on their fellow, corrupted citizens, the narcomaniacs and drug peddlers, the lowest of the low.

Royal Copeland, President of the Board of Health for New York City told the New York Times in 1919, “in the underworld of New York you will find 10,000 drug addicts, and every crime of violence committed you may know has been perpetrated by one of them.” A year later Dr Donald Murray, MP for the Western Isles, warned parliament of a “great evil in the social structure of our country…habits learned, developed and practiced, especially in the bigger towns, amongst certain sections of the population.”

The civil war and the ignorance created by the new drug concept is still in place today. While there have been great efforts to help people addicted to drugs, the people who use and sell them are still stigmatised, scapegoated and duly banged up. In America, the links between the drug war and ethnic minorities is well established. Globally, for decades, the war on drugs has become a legitimised tool to oppress and execute undesirables.

The fragility and artificiality of the invented ‘drugs’ bag has unravelled in the last decade. In Britain the government was forced to delay the start of its Psychoactive Substances Act 2016 for seven weeks because it got lost in a philosophical and scientific hall of mirrors trying to work out exactly what constituted an ‘illegal’ drug and indeed, what a ‘psychoactive drug’ was in the first place. The expanding market in psychoactive lifestyle drugs, such as the legal stimulant modafinil, has further blurred the old lines.

But there is a way out of this entanglement. The concept that got us into this mess offers a way out of it, says Seddon. The drug label must be broken up into its constituent parts if individual substances are to be addressed properly. Dealing with a rag tag of ‘drugs’ is like dealing with a vast array of mental health problems marked with derogatory catchall terms like ‘lunacy’ or ‘mad’.

The Madhouse by Goya – Dealing with a rag tag of ‘drugs’ is like dealing with a vast array of mental health problems marked with derogatory catchall terms like ‘lunacy’ or ‘mad’.

“If we wish to create a new regulatory regime for the psychoactive substances we currently term ‘drugs’,” says Seddon, “we need first of all to construct them differently as regulatory objects. We need to consider, for each type of substance, what type of market do we wish to see?”

When substances are singled out and removed from the drug bag, such as cannabis in Colorado or heroin in Switzerland, there is progress. Arguably the biggest success of Portugal’s decriminalisation policy has come about not because of the blanket policy regarding possession of all drugs, but because of the specific, unique attention paid to helping the users of one drug, heroin.

The term ‘drugs’ to describe a vast array of substances that just happen to make you high has enabled politicians and the media to lump them together in a way that is entirely negative. As Seddon has shown, it has coloured the way society acts towards the people who use them. Words can influence attitudes, but they are not immutable. The mythical world of people once called drug peddlers and dope pushers, thrill seekers and drug abusers, junkies and scagheads, is fading, it just sounds stupid and old fashioned, even for the tabloids now. And with less intoxicating labels, people are viewed with a different eye. It is not too unrealistic therefore to think that as we remove the invented line between bad drugs and good drugs, then it becomes easier to make policies based on individual substances rather than a mysterious assembly of pills and potions that made up the brain-addling frying pan of the 1980s.

In fact Seddon predicts that, like the lexicography of drugs, drug prohibition itself will turn out to be a momentary state, a ‘transitory period in human affairs’.

“Genealogy tells us that the modern notion of a drug is itself deeply embedded in the prohibition paradigm and implicated in its continuing survival,” concludes Seddon. “It will only be when the ‘false self-evidence’ of the drug concept is shaken hard enough that it falls apart, that we will finally see the arbitrary boundaries between intoxicants drawn a century ago disappear like markings ‘drawn in sand at the edge of the sea.”

Max Daly is a journalist and author who has published widely on drugs and writes the regular Narcomania column for Vice. His book Narcomania: How Britain Got Hooked On Drugs was published in 2013. Tweets @narcomania