I no longer drink alcohol.

It’s something I need to explain, because it’s something I don’t fully understand. This is a relatively recent thing, I should add. I have been dry for sixteen months, after nearly 50 years of… not being dry. My earliest exposure to alcohol came in a religious context. At my parents’ Passover table one year – I must have been five or six – I discovered that the sweet wine used in the service produced a dizzying sensation that was at once both frightening and funny. After that, I looked forward to the sips and small cups that punctuated Sabbath and festival observance, and which, with the benefit of hindsight, served as the nursery slopes of (much) more copious drinking as an adult.

In my first career, as a peripatetic double-bass player, alcohol was the sea in which we all swam. From my decade of small-time rock’n’roll rambling I remember only one musician who didn’t drink at all, and plenty who did little else. I don’t judge. I didn’t need anybody’s permission when I drank, and long after I had settled down with a family and a career in corporate communications I saw no contradiction between that settling down and the constant rhythm of the glass. Which, as Andy Fairweather Low once sang, is stronger than the rhythm of life. Or it can be. The glass dances to many rhythms, and the crooked timber of humanity has mastered and misused them all in ways that reflect the specificities of each timbrous time and place.

This is how it sounds in the Tenderloin…

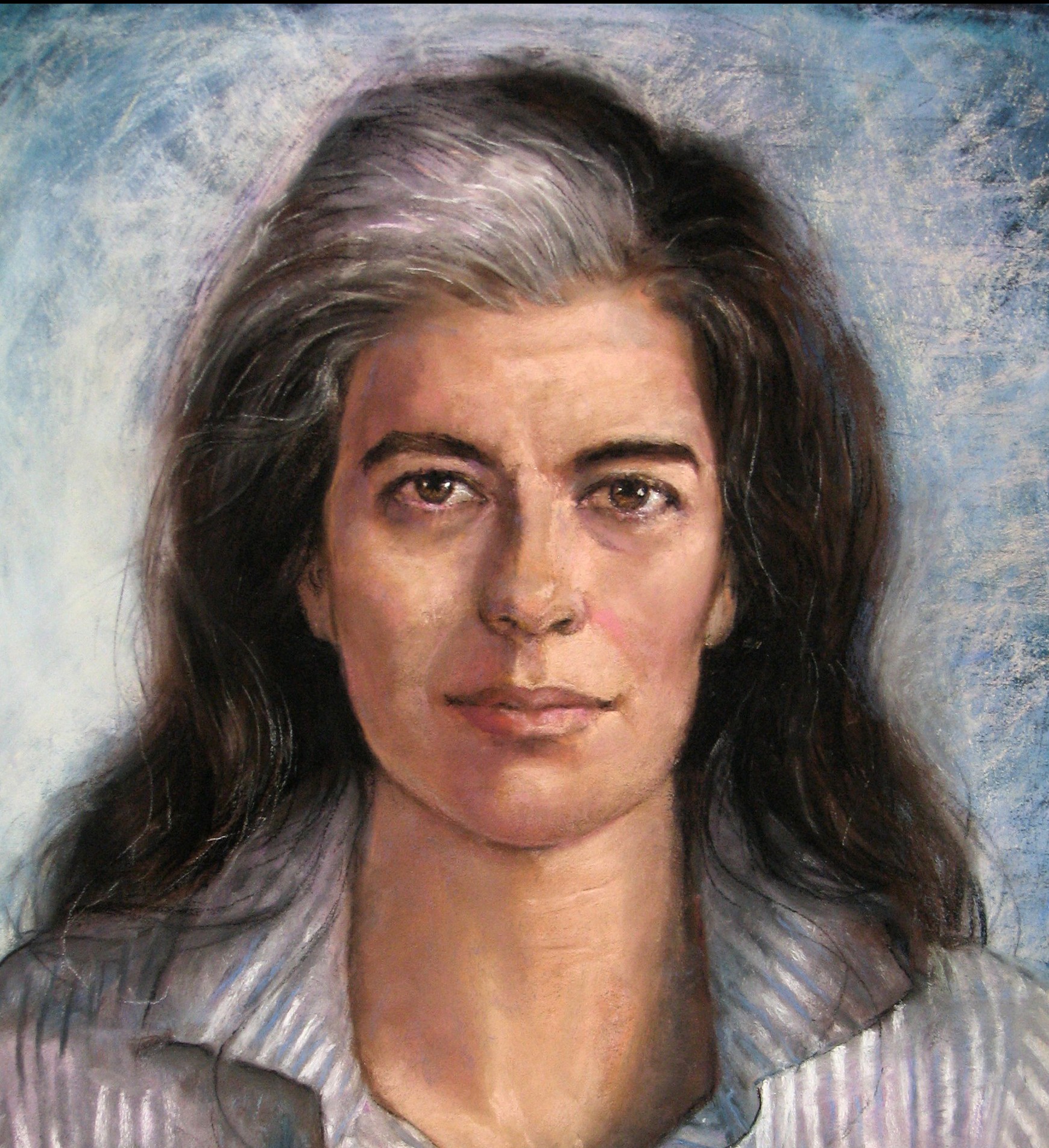

Fay Zenoff’s office sits on the sixth floor of a building on Market Street, between 7th and 8th Streets at the UN Plaza, in San Francisco. Until recently, she shared the building with the Art Institute of California, whose students grapple with gaming technology, fashion, visual design and a host of other creative interests as they pursue, the Institute’s website says, “problems to be solved. And futures to be formed”. Fay’s concerns are surprisingly similar, given that her organisation is apparently of a quite different nature. As Executive Director of the Center for Open Recovery, Fay is a leader in the recovery advocacy movement, a movement with a tradition that dates back at least eight decades but whose provenance and progress are not as well-known as they should be.

It was June 2015, and I was headed to San Francisco for a conference. I decided to add a few extra days to catch up with friends and spend some time in the city. A couple of weeks before the conference, the organisers invited me to devote the first afternoon to a session where conference delegates offer pro bono support to a local non profit. They sent me a list of organisations seeking help, and one name leapt off the page. I remember thinking, nobody will want to help them. Maybe I should. It was the National Council on Alcoholism and Drug Dependence, Bay Area (NCA-BA). And I was wrong, of course, because a colleague from Italy and two from Canada also volunteered. So the four of us sat down with Fay Zenoff and independent development consultant Yuki Mosher for the afternoon, to discuss NCA-BA’s plans for a rebrand and associated strategic communications. It was fun. We all got on well, and Fay and Yuki left with a rewritten vision and mission statement, an outline plan for the rebrand, and suggestions for keeping stakeholders informed and engaged.

I arranged to visit Fay at her office in the Tenderloin district after the conference, to discuss communicating the rebrand with her staff and governing board. She emailed me directions, adding “Happy to meet you somewhere if you have any hesitance about walking in the neighbourhood.” Hesitance hadn’t occurred to me. I once strolled from Baltimore’s tourist-friendly Fell’s Point area to the downtown church where Edgar Allen Poe is buried, oblivious to the fact that I was crossing streets notorious for their homicide rates. And I hadn’t read articles like the Quora page headed ‘How dangerous is the Tenderloin, really?’ (The answers are mixed, and feature the words ‘sketchy’ and ‘funky’.)

So I struck out that Thursday morning along Market Street, amidst the sunshine and bustle of summertime shoppers and tourists, finding my way to the Art Institute without trouble. After talking with Fay and meeting some of her team, Fay offered to take me on a brief walking tour of the area. As we set off, she told me about the 79 liquor stores that inhabit just 44 Tenderloin blocks, describing the programme her organisation runs to persuade storekeepers to move liquor to the back of the store and put fresh fruit and vegetables near the counter, along with free leaflets from NCA-BA on healthy eating. A classic ‘nudge’ policy, it encourages some of the many single-occupancy dwellers within the Tenderloin to think a little more carefully about what they put into their bodies. It’s effective, but just a small part of the services Fay and her staff offer to those coping with the consequences of drug- and alcohol-related problems.

As we walked, we saw people in variously distressing situations; homeless and hungry, high on drink and drugs, some lying unconscious (or worse) in the street. And each may as well have been wearing a placard stating ‘this is my fault’, because that is how their predicament is so often regarded by others. As my initial reaction to the name National Council on Alcoholism and other Drug Dependence shows, I was far from immune to such prejudice. But the little time I spent with Fay helped me to realise that this is the attitude that perpetuates so much of the misery. Because as problem drug users, these people are prey to unscrupulous dealers and other criminals; while as sufferers in need of treatment, they are frequently denied the basic care that others with less stigmatised illnesses take for granted.

Others like me. The support available in my recovery from cancer has been excellent, and unconditional. Even after five years of remission I have access to a wide range of physical and psychological care to help me cope with life after treatment. But it hasn’t always been like that. As Siddartha Mukherjee recounts in The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of Cancer, a breast cancer survivor in 1950s America wanted to set up a support group for women. She rang the New York Times to place an ad in the classified pages. After a pause, the clerk told her “I’m sorry, Ms. Rosenow, but the Times cannot publish the word breast or the word cancer in its pages.” We might scoff now at attitudes like that, but we have sought to impose the same silence on the victims of other diseases in the last fifty years, notably HIV/AIDS, and addiction.

It begins with language. In Illness as Metaphor, Susan Sontag brilliantly skewers the verbal images that generate the “punitive or sentimental fantasies” which characterise language about certain illnesses. In the 1970s, when she wrote the book, cancer was still considered such a taboo that many physicians lied to their patients, only sharing their diagnosis with the patient’s closest relatives. Compare that with today’s wall-to-wall TV coverage of Stand Up 2 Cancer campaigns. And it would be unthinkable to incarcerate cancer sufferers, instead of caring for them. Yet that’s exactly what we do to many problematic drug users.

The costs of such punitive fantasies acted out as policy are staggering. In the United States alone some $350 billion a year is consumed by responses to drug and alcohol addiction, through lost productivity, health care demands, and criminal justice costs. Of that sum, just two per cent is used for prevention or harm reduction. It is not because the Federal government deems this a good use of public resources, but because public perception has largely represented addicts and alcoholics as moral failures, with a rich vocabulary of pejorative and insulting terms that trap people in disease and deceit. And as the author William Cope Moyes tells Greg Williams, in the latter’s absorbing 2014 documentary The Anonymous People, “public perception drives public policy.”

This is why Fay Zenoff wanted to rebrand NCA-BA; to reframe its role, as she told me recently, in a way that ended nearly six decades of a focus “on prevention and treatment, not sustaining recovery.” The rebrand did not signal a move away from the original purpose of founder Margaret ‘Marty’ Mann. Far from it. As one of the first women to join Alcoholics Anonymous, Marty Mann was a tireless campaigner for recovery not recrimination, and for openness not opacity (while respecting the validity of the original 12-step value of anonymity). Creating the Center for Open Recovery represents another step on the road to advocacy’s triumph over discrimination, a testament to the fact that recovery from addiction is possible, and a promise that eventually the stigma will end.

I did not return from San Francisco vowing to abstain. It just happened. But whether it was the sights and sounds of the Tenderloin, or the facts and figures of addiction, or the fundamental justice of the case for open recovery, it seems self-evident now that someone’s addiction is no more cause for persecution than was my cancer, and that access to the means of recovery is a right, regardless of the nature of the illness. Does any of this explain why I no longer drink? Maybe. Whatever the case, I am proud to be associated with the millions who are living in recovery, and to share the hope of recovery for millions more.

Ezri Carlebach is a writer, lecturer, and consultant, and a Fellow of the Royal Society of Arts and the Institute of Internal Communication. He writes here in a personal capacity. Tweets @ezriel