Yesterday, the Global Drug Commission, chaired by former UN General Secretary Kofi Annan, released a report investigating the way drugs and drug users are perceived and how it impacts them.

The report, called ‘The World Drug Perception Problem’, finds that the perception of people who use drugs is generally negative, leading to their stigmatisation and discrimination.

The Commission believes that in order to change how drug consumption is perceived, there must a concerted effort to alter the language currently used to discuss the subject.

According to the report, this stigmatisation is so profound and subconscious that even the scientific community is discriminative when talking about drugs and drug users: “even trained mental health professionals who were given identical case studies – but where in one the patient was referred to as ‘substance abuser’, and in the other as ‘someone with a substance use disorder’ – were more likely to believe that the patient in question was personally culpable and that punitive measures should be taken when the term ‘abuser’ was used.”

According to the report media and political leaders are partly responsible for this perception. The media, in particular, are highlighted: “two narratives of drugs and people who use them have been dominant: one links drugs and crime, the other suggests that the devastating consequences of drug use on an individual are inevitable”.

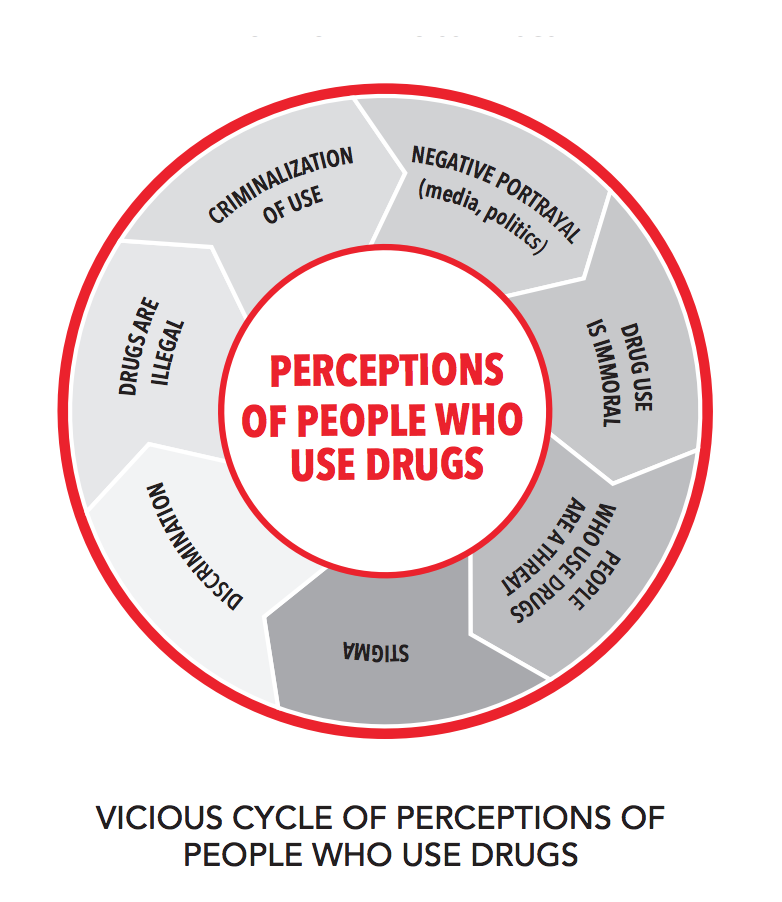

By using negative language such as ‘junkie’, ‘crackhead’, ‘clean’, or drug addict’, they lead the general public to develop a negative image of drug users and discrimination is likely to increase. This terminology encourages people to think drug users are marginal, morally flawed, or even “inferior individuals” according to the report. This attitude toward drug users has the effect to make people believe drugs are illegal for good reasons. In return, this perception leads the public to discriminate against drug users even more.

This vicious cycle of perception can hinder efforts to develop alternative policies and generate public support for reform.

The pejorative terms which are used, and the negative perception emanating from them can give the debate around drugs a moral dimension rather than a scientific, fact-based one. The Commission explains that the primary assumptions the general public has toward someone using drugs is that they are ‘weak’ or ‘immoral’. Another stereotype of people who use drugs cited by the report is that of people living “on the margins of society, who are not equal members of it or entitled to the same rights as others”.

This perception blinds the general public’s view on drugs, which prefers to associate them with a deviant social attitude rather than an activity largely existing in all cultures and less harmful than we think.

However the Commission found the exact opposite. According to the report, an estimated quarter of a billion people (aged 15-64) currently use illegal drugs, of which only 11.6% are considered to suffer problematic drug use. This data suggests two things. First, drug consumption is more common than we think. Second, most drug consumption is episodic and non problematic.

Nick Clegg, former Deputy Prime Minister of the United Kingdom and member of the Global Drug Commission, said:

“Current drug policies are all too often based on perceptions and passionate beliefs, not facts. Any drug use carries risks, but only a small number of people who use drugs go on to face addiction or dependency. Those who do develop problems need our help, not the threat of criminal punishment.”

Other data from the report shows that ‘lifetime drug users’ (individuals who have taken a certain drug at least once in their life) are much higher than those who have ‘used in the past year’ for all substances. In the EU for example, there are: 87.7 million lifetime users of cannabis vs. 23.5 million yearly users, 17.5 million lifetime users of cocaine vs. 3.5 million yearly users, and 14.0 million lifetime users of MDMA vs. 2.7 million yearly users, all of which indicate that most people who try a drug do not become dependent or frequent users.

However, for those with problematic use, the report recommends a wider range of treatment options should be made available to people who seek it.

Addiction is often perceived to be permanent and irreversible. Even though recovery is possible, health authorities perceive abstinence as the best way to go for treatment. However if we are promoting physical and mental wellness, then abstinence may not be the way to go. Complete abstinence can be source of anxiety and damage a person’s mental health in the long term. Therefore large options of treatment should be available. The report suggests needle and syringe programs, safe injection facilities, provision of opioid-overdose antagonists, and drug checking as some options that should be made available.

Our Policy Adviser Paul North, with 9 years of experience working in Drug Treatment services agrees this is the case.

Addiction is a symptom of a problem, not the cause. Interventions should focus on the individual, and look far beyond the use of any drug. While for many abstaining is a recommended and viable option, such a label does not define a problematic relationship. Addiction is about why a drug is being used, not how often. Good treatment allows the individual to make their own choice around frequency of use rather than provide a strict guideline or label. – Paul North, Policy Adviser, Volteface

In the UK, policy alternatives with a focus on harm reduction are slowly emerging. Whilst Glasgow is looking to open a drug consumption room, The Loop started to offer drug testing services in festivals throughout the UK. This report provides further evidence of needed policy reform in the UK.

Pierre-Yves is Communications Officer at Volteface. Tweets @PYGallety