This article was originally published by Transform.

Key policy questions around the future of dance drugs in the UK have, this year, crystallised around two profoundly contrasting events: the closure of Fabric for what Islington Council deemed its failure to tackle the nightclub’s ‘culture of drugs’, and the introduction of drug testing for individual users as part of pragmatic drug harm reduction response at two UK festivals (Secret Garden Party and Kendal Calling). These two events could hardly be more different, representing the Yin and Yang of UK drug policy.

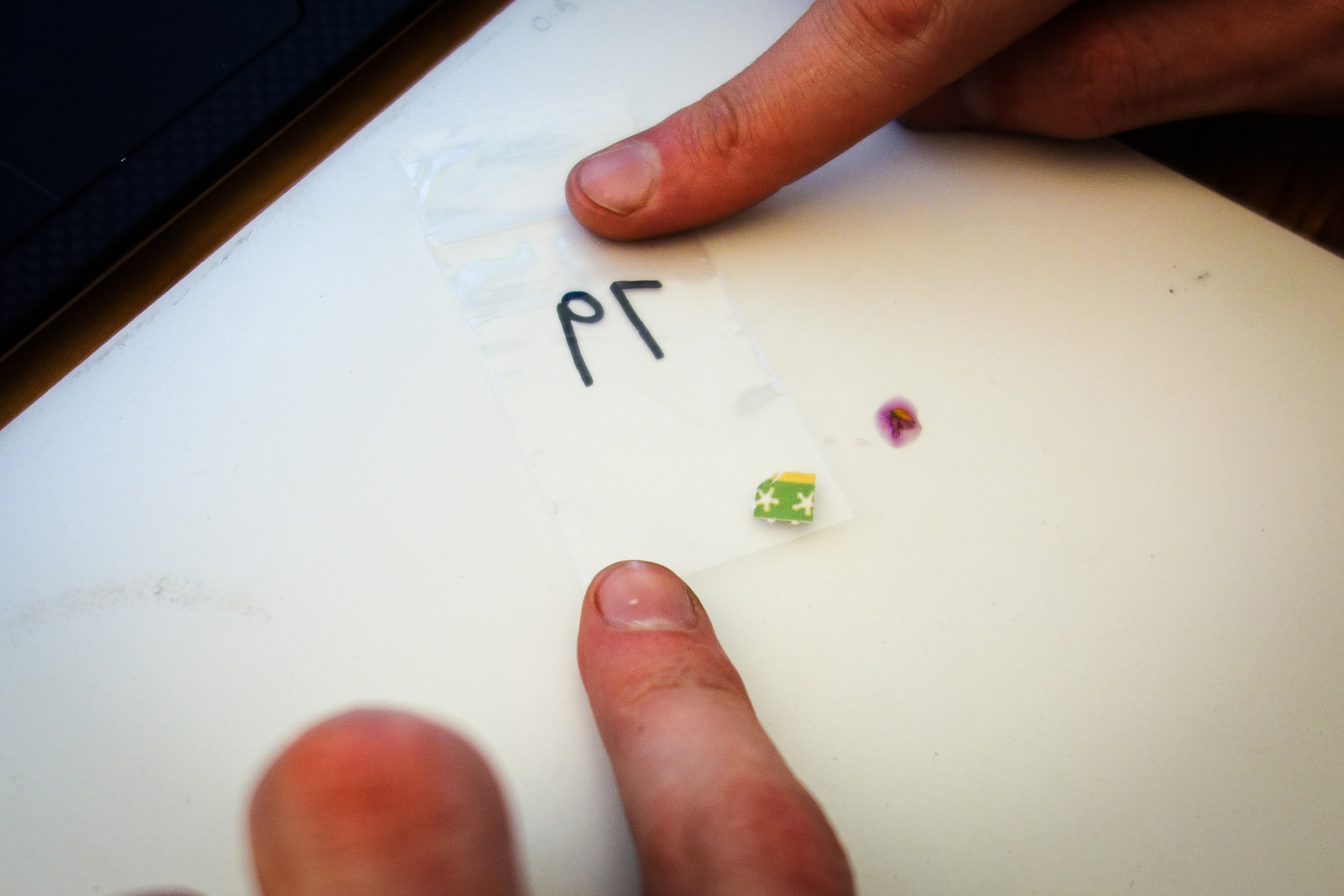

The introduction of Multi Agency Safety Testing (MAST) provided by the volunteer drugs service The Loop at Secret Garden Party represented a huge step forward. It was the first time ever in the UK that drug users were able to take substances of concern for a range of forensic tests conducted by Loop staff and receive the results of those tests half an hour later as part of an individually tailored harm reduction package. Upon discovering the contents of their illegal wares, ranging from boric acid to malaria tablets and even concrete, a quarter of users chose to dispose of their drugs rather than consume them.

Establishing the festival-based advice and ‘drug checking service was the result of years of pioneering harm reduction work and careful negotiations by The Loop’s Director, co-author Professor Fiona Measham. Critically, it depended on securing agreement between the event organisers, police, local authorities and public health officials. The result may seem paradoxical: a drug testing service, effectively a decriminalised drug space, at an event with a stated ‘zero tolerance’ drug policy. But such paradoxes are inevitable in the current legal and policy environment where drugs are illegal and their users are criminalised. Yet despite this, millions of people choose to take illegal drugs in the UK. The authorities are pragmatic by necessity; they must balance a nominal requirement to enforce failing and discredited punitive drug laws against a responsibility to protect the health and welfare of thousands of people using drugs at leisure events.

If the authorities at Secret Garden Party and Kendal Calling made the decision to prioritise the health and welfare of drug users over punitive enforcement targets, the story of Fabric’s closure witnessed the balance swinging dramatically in the opposite direction. The club had probably the most stringent security and search policies of any venue in the UK, if not the world, but the reality is that drugs are small, potent and easily concealed. You simply cannot stop drugs getting into clubs. Worse – more intensive security measures may often encourage riskier drug use. For example, people may consume all their drugs at once outside a venue if the security looks intimidating (a view supported by the judge in the previous Fabric review of December 2015), or be less able to gauge how much of a drug they are taking if the activity is necessarily surreptitious once inside a venue. The deaths at Fabric were tragic but the reality is that the ever intensifying demands by authorities for more drug enforcement actually made putting in place more effective harm reduction – such as drug checking –impossible. At no point in the often Kafka-esque license hearing did police or council acknowledge any responsibility for creating a legal and policy environment that made such tragedies more, rather than less likely.

Going forward the way seems clear. Since the summertime The Loop has been besieged by requests to set up MAST at other events next year and is now working to help facilitate a roll-out by sharing expertise and establishing a training and accreditation organisation supported by the events industry, venue management, trade associations and other stakeholders. Nightclubs face different challenges to festivals, however, and sophisticated on-site testing will rarely be practical or financially viable. Plans are afoot to pilot alternatives including city centre testing and advice kiosks, as well providing guidelines for best practice. Testing services are not the panacea to all problems created by drug use and its ongoing criminal status, but until the UK stands down from its ideological ‘war on drugs’ footing and drugs are available via a responsibly regulated legal market, they are a vital missing piece of the jigsaw if we are serious about avoiding more deaths and hospitalisations.

Drug use cannot be wished away and rising use over the past half century shows it cannot be eradicated by punitive enforcement either. We do not and never will live in a drug-free society. That basic reality has to be the starting point for any responsible policy maker concerned with the health and welfare of its citizens. Do we close all nightclubs and engage in mass arrests at festivals? Or do we attempt to pragmatically manage the reality of drug use as it currently exists so as to reduce the harms it can cause?

Fiona Measham is Professor of Criminology at Durham University, Co-founder and Director of The Loop drug, alcohol and sexual health service, and Member of the Advisory Council on the Misuse of Drugs. Tweets @FMeasham

Steve Rolles is the Senior Policy Analyst at Transform, the British based think tank providing world class research to the global drug policy debate. Steve authored the briefing paper, ‘The War on Drugs: Harming, not protecting, young people’. Tweets @SteveTransform