The Economist have published a comprehensive explainer on the ‘dark web’, the secret online marketplace for drugs, exploring the functions of networks such as ‘Silk Road’ in addition to the trials and tribulations of ‘dark web’ entrepreneurs.

Online drug markets are part of the “dark web”: sites only accessible through browsers such as Tor, which route communications via several computers and layers of encryption, making them almost impossible for law enforcement to track. Buyers and sellers make contact using e-mail providers such as Sigaint, a secure dark-web service, and encryption software such as Pretty Good Privacy (PGP). They settle up in bitcoin, a digital currency that can be exchanged for the old-fashioned sort and that offers near-anonymity during a deal.

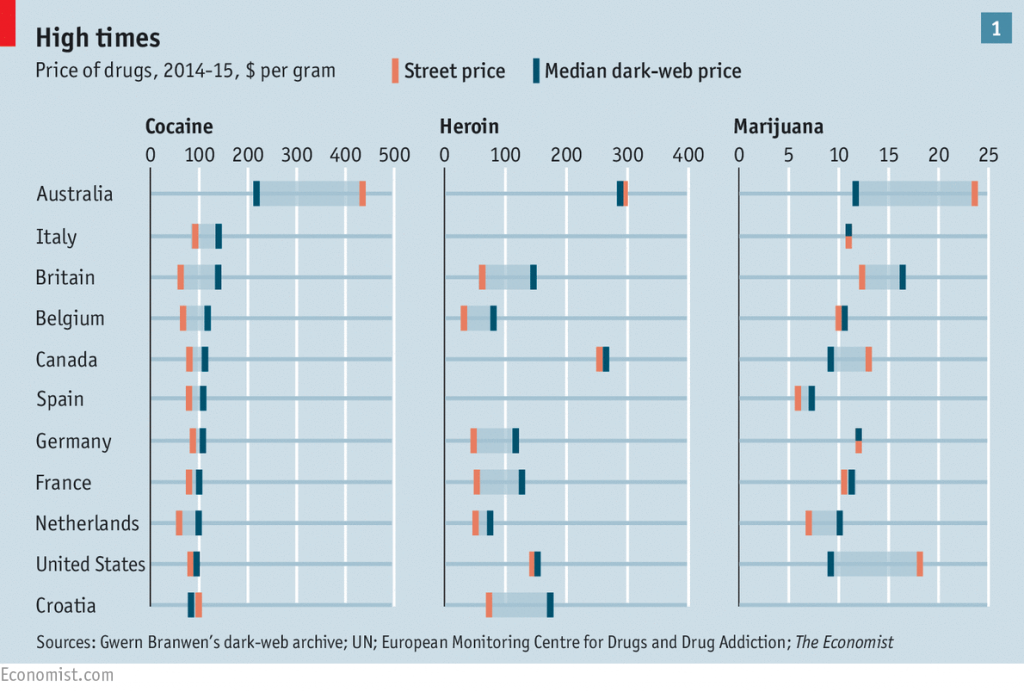

The article also reveals extensive data, unearthed exclusively for the report, that exposes purchase and seller data from a number of ‘dark web’ sites in extensive detail.

In addition to revealing the almost doubling of drug users purchasing substances online – from 8% in 2014 to 15% in 2015 (via the Global Drugs Survey), the article also proffers a variety of insights into the behaviour of a previously guarded market:

MDMA (ecstasy) sold the most by value (see graphic). Marijuana was the most popular product, with around 38,000 sales. Legal drugs such as oxycodone and diazepam (Valium) were also popular. A third of sales did not belong in any of our categories: these included drug kit such as bongs, and drugs described in ways that buyers presumably understood, but we did not (Barney’s Farm; Pink Panther; Gorilla Glue).

Potential perils and pitfalls of buying drugs online are also explored. The market relies heavily on positive reviews and feedback from customers, however, dangers and scams still prevail for the unsuspecting and the uninitiated:

For most drugs, though, cryptomarkets allow dealers to avoid the dangers they face on the street. They no longer run such risks as being shot by a rival or stabbed by a junkie. Customers are less likely to be arrested, or sold dodgy products. But there are also new dangers.

Ms Aldridge points to “doxxing”—the release of personal details online—as one. An aggrieved (or opportunistic) vendor who thinks a customer’s review was unfair may publish the delivery address or threaten blackmail. On a forum, one user complains that he received a letter postmarked Hawaii saying that someone “has my info and he’s going to give it to the cops” unless five bitcoin ($1,217 at the time) are sent to an untraceable account. And cryptomarkets themselves have suffered distributed denial-of-service attacks, in which a website is brought down by a flood of bogus page requests. These may be orchestrated by rivals who want to grab market share, says James Martin, a cryptomarket expert at Macquarie University in Australia, just as offline gangs engage in turf wars.

All in all, the piece provides a valuable primer on the operations of a previously under reported and under explored sector of the drug market.

As customers increasingly opt to access and purchase their substances of choice online, reporters will have to tow the fine line between safeguarding against the potential hazards of the market, and exposing its inner workings to the greater public.

Words by Calum Armstrong. Tweets @vf_calum