Growing out of a community and street campaign in the 1990’s, CityWide has developed into one of Ireland’s most important drug policy reform advocates.

We sent Brian Houlihan to meet with Anna Quigley in their headquarters in Fairview to help us trace not only their organisation’s history, but the history of modern Irish drug campaigns.

CityWide is a network of community activists and organisations that united to find a response to Ireland’s drugs crisis.

Grassroots development

CityWide has many objectives, central to their work. Amongst these is developing the capacity of communities to respond to the drugs problem in their area. They provide ongoing support, facilitation and networking to local groups working on the issue.

Political campaigning and lobbying

On top of this grassroots development, CityWide looks to campaign and lobby on drugs policy issues, representing the community sector on policy boards. They also encourage an inter-agency response to the drug problem. They want to see government departments and agencies, trade unions, community and voluntary bodies and other relevant agencies work together.

Network creation

CityWide helped create many networks which assist communities affected by drugs . One example is the National Family Support Network which offers support to families affected by substance misuse. A recent survey found that 80% of the National Family Support Network members support the decriminalisation of drug use.

Representing and defending both communities and people who use drugs

Providing a voice for drug users and communities affected by drugs is a key aim of CityWide. They also play a role in holding the media and others to account. In 2011 they were part of a group which complained against a journalist’s use of derogatory language towards drug users. Alongside engaging with the media, Citywide has also produced short documentaries addressing issues relating to drugs.

In its representative capacity, CityWide plays a key role on numerous committees, networks and advisory boards. They participate on bodies such as The Oversight Forum on Drugs, The National Advisory Committee on Drugs & Alcohol, The Prisons Liaison Group and The National Drug Rehabilitation Implementation Committee.

International Attention

CityWide has hosted conferences on various drug issues which featured local and international experts. In 2010 they organized a conference looking at the issue of Irish criminal gangs. At their 2013 conference, CityWide first raised the idea of decriminalisation when they launched a leaflet highlighting the issue.

CityWide recently celebrated its 20th anniversary with an informative conference held at Croke Park. Among the distinguished guests was the Irish president Michael D. Higgins who gave a compassionate speech.

Representatives of the organisation have appeared before various government committees over the years, while behind the scenes their team has produced a number of policy documents and publications. CityWide should also be praised for their support of Irish minority groups such as Travellers and for their work with the LGBT community.

CityWide is a fine example of how a community based group can stay true to its roots while growing into an internationally respected organisation.

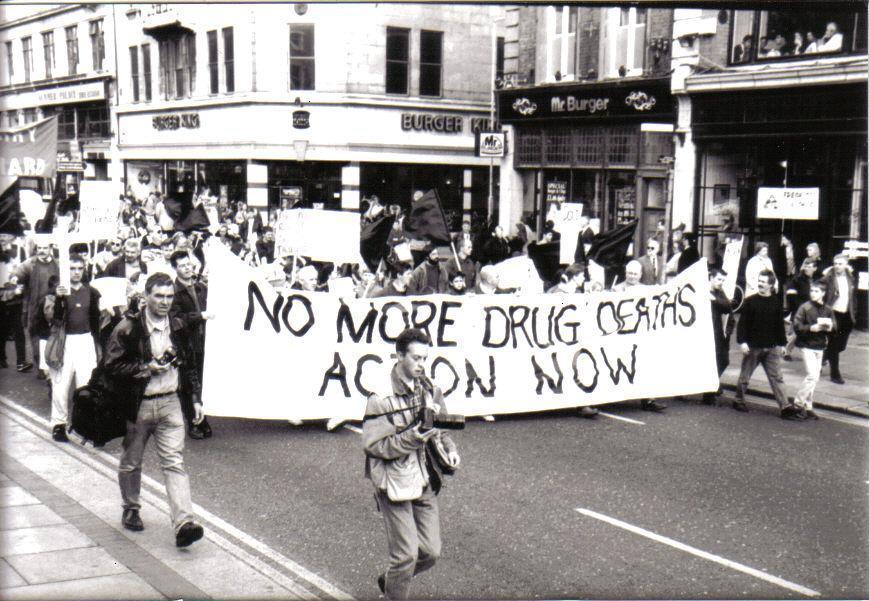

From activists organising street protests, to speaking before government committees and hosting the President of Ireland, CityWide’s influence has grown steadily over the years.

So where did CityWide come from?

Recently I spoke with Anna Quigley to get her valuable insight into CityWide, and how the drug crisis in Ireland has evolved.

Anna has worked with CityWide since its inception. She was part of the campaigns and community groups from which CityWide emerged, and has also served as a local councillor for Dublin North Inner City.

The first meeting of CityWide was held in the Liberty Hall in September 1995, conducted by the Inner City Organisations Network, where activists from various community groups came together.

The drug crisis had been growing for the previous two decades.

Since the late 1970s communities in Dublin’s inner city had tried to respond to the situation. The extent of the crisis is unimaginable. Research in 1983 known as the ‘Bradshaw Report’ revealed that 10% of 15 – 24 year olds in the north inner city had use heroin at least once.

Anna believes that the crisis that led to the creation of CityWide was “quietly spreading without much attention”. Many in the communities affected by the drugs crisis in the 1990s felt it was largely due to the inadequate state response to the roots of the crisis in the 1970s and 1980s.

The initial role of CityWide was to ensure that the state response was more substantial this time around. There was little political support for the issue, although unions such as SIPTU did provide assistance.

The community campaign from which CityWide emerged is largely misunderstood and often misrepresented.

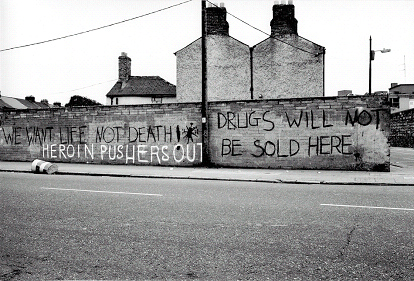

These communities in the inner city, which were bearing the brunt of the crisis, began to take matters into their own hands. Actions such as: street protests, the naming and shaming of dealers, forced evictions, patrols of areas and others were used by community activists.

These tactics soon drew criticism from politicians and the media. Community activists were branded as vigilantes and wrongly portrayed as Republicans or other dissidents. Regarding the tactics deployed by the activists, Anna states that “looking back now, people can see the damage it did within communities. It turned people against their neighbours”.

The community turned to such tactics because “people were acting out of desperation”. Anna suggests that these communities believed they had no other action left to take, and “back then nobody had a real sense about the nature of drug use”. She believes many people in communities didn’t tie it into their wider social circumstances.

The media was quite critical of the campaign and is perhaps responsible for how issues around drug use are perceived today.

“The media didn’t focus on why these people are doing this”

Anna believes the media was more interested in linking activists to republicanism than assessing the crisis. While Sinn Fein politicians and supporters did participate, the claims the community movement was dissidents appear unfounded.

What is often overlooked is the other forms of direct action undertaken. I was told the story of a woman in Crumlin whose family had been affected by heroin. Anna says “she went and found a hall and a doctor who would prescribe methadone”. The woman essentially established a de-facto methadone clinic in order to help others.

Anna highlights that “while people were involved with protests they were also trying to get services for people”. This is an aspect which is perhaps forgotten now. Arguably the tactics used did lead the authorities to finally intervene, even if it was initially to arrest a number of the activists. These community actions did at least draw attention to the wider drugs crisis.

The pressure from activists helped lead to the establishment of a governmental task force in 1996.

The Ministerial Task Force on Measures to Reduce the Demand for Drugs eventually released what is known as the Rabbite Report. The report stated that this problem was concentrated in the poorest areas.

Around this time there was another significant event that brought the drug crisis to the fore.

The next time drugs were to appear in the fore front of public debate was in the aftermath of a bloody execution.

In June of the same year, a journalist named Veronica Guerin was killed by members of a drug gang. Guerin had been investigating Ireland’s criminal underworld for some time. Unaware she had been followed, two men pulled up on a motorcycle and opened fire on her as she sat in her car. Her death shocked the nation.

The outcry following her killing would see the Irish state intensify its efforts to tackle drug crime.

Within a week of her murder the government enacted two pieces of legislation, the Proceeds of Crime Act 1996 and the Criminal Assets Bureau Act 1996. Both acts allowed assets that were purchased with proceeds of crime to be seized by the state. The Criminal Assests Bureau was established to undertake such actions. This was a success for CityWide, as they and others had been calling for such an organisation to be established prior to Veronica Guerin’s death.

Anna tells me that “there is no question that her death had a major impact because it made drugs an issue for broader Irish society”, and suggests the media, especially the Irish Independent for which Veronica Guerin worked for, were now more interested in highlighting the issue. What was once seen as only relevent to disadvantaged areas soon became a topic of national discussion.

While the state may have responded swiftly in tackling the proceeds of crime, arguably little was done to establish services for drug users.

During the 1990s Anna tells me “there were very limited services available for users” and that “during the Celtic Tiger [economic boom years] there was no willingness to acknowledge that this problem is connected to broader social issues”.

CityWide played a key role in getting the Drug Task Forces established across the country. These Drug Task Forces would provide drug services for users. However, even to this day, a gap still remains between the services needed and the number that are available. Anna tells me that “once you start creating services you have to invest in them, as the needs only begin to emerge. Soon you realise there are other services you need”. At times it has been a struggle to obtain funding.

CityWide has tried to change attitudes in Ireland towards drugs and arguably this year has been one of the most significant.

In March of this year CityWide led the cries for a Junior Minister to be given the role of developing the National Drugs Strategy. Labour TD Aodhán Ó Ríordáin would be given the role a number of weeks later and since then the debate around drugs policy has intensified in Ireland. Discussions on issues like decriminalisation and medically supervised injection centres have become more common place.

On the impact of Aodhán Ó Ríordáin’s appointment, Anna states “you can see the difference a committed Minister makes”. The “genie is out of the bottle”, she observes, and that it is certainly easier now to vocalise support for decriminalisation and other issues around drug use. “Political leadership is crucial” for seeing effective policy change, Anna claims. “We have seen the extent to which a Minister can provide leadership in this” she adds.

A government committee travelled to Portugal to assess their change in policy over 15 years ago. That change in Portugal saw authorities adopt a policy of decriminalisation. The government committee released a positive report on their findings and later made a number of recommendations following a public consultation process on decriminalisatrion. CityWide participated in the consultation process. However, Anna is cautious about any potential changes in policy and states that “actually implementing it will take a good bit longer”. She highlights that “on their own a Minister can’t change things” rightly suggesting that they need the backing of their party, the cabinet, civil service and other agencies.

The next few months are crucial for groups like CityWide with a number of important events coming up:

- There is a new National Drugs Strategy due next year which will provide the blueprint for drug policy over the coming years.

- A new Misuse of Drugs Act is due which should allow for the introduction of a medically supervised injection centre in Dublin.

- The upcoming elections in Ireland which means we are likely to have a change of government before any mooted changes are fully implemented.

Despite the air of positivity around policy change, there is also a lot of uncertainty.

One certainty is that groups like CityWide and activists like Anna Quigley are going to play a key role in Ireland’s ever evolving attitude and policy towards drugs, building on more than two decades of work.

You can visit www.citywide.ie to learn more.

Words by Brian Houlihan

Photos courtesy of CityWide

Editor’s Note: On December 15th, it was reported that the Irish cabinet approved a pilot scheme for a medically supervised drug injection facility in Dublin due to the work of advocate groups and Minister Ó Ríordáin.