Use of synthetic cannabinoids (aka ‘Spice’), as reported extensively in the mainstream media, has recently become a major problem among the homeless community and in prisons. Spice is cheap, hard to detect, has hugely variable levels of potency and comes with some severe adverse effects.

Huge stress is being put on the prison and health systems, with reports of ambulances being called out almost continually to Manchester city centre and daily to many prisons for spice-induced medical emergencies. Many vulnerable people who take spice are risking their lives on a daily basis. It can have extremely harmful effects on the body and has been known to stop hearts and induce suicide.

New Psychoactive Substances (NPS) is an umbrella term for a variety of drugs like spice that were designed to imitate traditional illegal drugs. They were all made illegal themselves last year with the Psychoactive Substances Act, yet use of spice is still on the rise, particularly in the homeless population. The mortality rate from deaths involving NPS, whilst still dwarfed by that for heroin, have increased sharply in recent years, with 114 deaths registered in 2015 (up from 82 deaths in 2014). Whilst we do not know for sure how many of these were spice-related and how many were related to other NPS, spice has one of the highest rates of use and is one of the most dangerous, so it is likely to be responsible for the rise in deaths.

Talking about systematic problems causing people to take spice are absolutely key to resolving the ‘spice crisis’, as well as discussing treatment, homeless services and prison reform. However, what no one seems to be talking about is what can be done to help people suffering from the acute effects of spice use. An antidote for spice, similar to naloxone that is used to treat opioid overdose, could be a real help to paramedics and other frontline health staff.

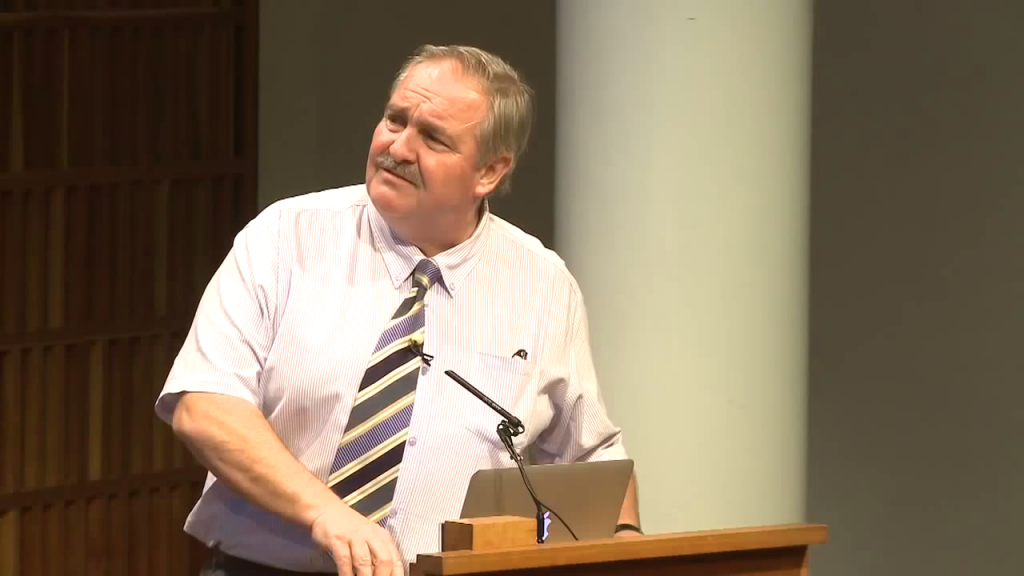

David Nutt, Professor of Neuropsychopharmacology at Imperial College London and former government drug advisor, has suggested that there are a number of potential spice antidotes that should be investigated, including two antagonists – Rimonabant and THCV. He put forward a proposal to the government in January to develop the possibility of re-introducing rimonabant, a potential antidote for spice, and for more research to be conducted on the subject.

Spice simulates cannabis by acting on the CB1 receptor in the brain, but to a far greater extent than cannabis does, which is what is causing all these new problems. Rimonabant is an antagonist of the cannabis CB1 receptor. It was initially investigated by Sanofi, a French pharmaceutical company, about 20 years ago, who wanted to treat schizophrenia. However, their research found that rimonabant reduced appetite and was consequently licenced as a medicine to prevent weight gain after a person quits smoking. Unfortunately, the side effects of long-term use included a drop in mood and suicidal thoughts and so the drug was dismissed by the FDA and removed from sales worldwide.

This is where its potential as an antidote comes in. Rimonabant was also found to be a reversal agent for cannabis in the same way as naloxone is for heroin. Since cannabis and spice work on the same receptor, there is a good chance that it could work on spice. Crucially, the negative side effects seen when taking the drug long-term are unlikely to be experienced from a single dosage of antidote. Moreover, whilst there are understandably some concerns about rimonabant’s safety profile in the general public, the idea is for it to be developed as a potentially life-saving antidote, so possible side-effects would have to be pretty severe to be worse than death.

There are also questions about the comparative binding affinities of rimonabant and some of the most potent spice on the streets. Whilst rimonabant has a high potency and selectivity for the CB1 receptor, if the binding affinity for the spice causing the overdose is stronger, rimonabant may not be able to be an effective antagonist. Whilst rimonabant worked on cannabis and early synthetic cannabinoids, it has not been tested on more recent spice samples which are far more potent. Nevertheless, this is exactly why research needs to be carried out – to answer these sorts of questions.

Nutt claims that the response he received from the government was less than enthusiastic. The Justice Secretary Liz Truss replied that they were too concerned about the possible adverse effects of rimonabant, even though these effects have only been shown for long term use and safety checks would be a significant part of the research. Health Secretary Jeremy Hunt replied that it was up to Sanofi, the owners of Rimonabant, to pursue this through the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA).

Sanofi have been contacted about researching rimonabant and its potential as a spice antidote. At first, the Business Development Directors responded that out-licensing of the molecule was not a strategic priority for them, but have been put in touch with the Corporate Social Responsibility team. However, even if Sanofi were on board, government intervention is likely to be required to fund, distribute and develop the drug. Professor Nutt told Volteface:

“The failure of the UK government to even consider resurrecting a proven antidote to spice is a serious mistake that will result in many preventable deaths and a vast amount of wasted NHS resources over the coming years.”

But rimonabant isn’t even the only option. There are 100s of compounds in the cannabis plant that haven’t been studied due to its controlled nature, some of which have potentially therapeutic effects. For example, THCV is a cannabis derivative shown to have anti-epileptic properties and has potential to help with obesity, anxiety and schizophrenia. THCV also looks like it has THC-antagonist effects (THC being the cannabinoid that produces the ‘high’) and could be a useful antidote for the psychosis-producing effects of spice.

However, due to THCV’s Schedule 1 status, which indicates that it has no medical value, it is very difficult to conduct research on. As Professor Nutt said: “Drugs can only escape Schedule 1 if they can be demonstrated to have medicinal value, yet because they are schedule 1, research with them is almost impossible.” Licences to conduct research on these substances are very expensive and can take years to be granted, which puts off many researchers who may be interested in investigating their effects.

Having said this, the licences would only be a fraction of the total cost of such research. A licence for using the most restricted drugs can cost around £4,000 outright (cheaper to renew) whilst the costs of carrying out the research itself can reach hundreds of thousands. However, THVC’s Schedule 1 status does add obstacles and make it harder to conduct research, which is a quite unnecessary state of affairs, especially considering it could be a potential antidote – or at least a starting point.

Late last year, a number of psychopharmacology experts, including Professor Robin Murray from the Institute of Psychiatry at Kings College London asked the Advisory Council on the Misuse of Drugs (ACMD) to review the status of THCV as their experience was that it has very little potential for abuse, because it is in fact an agonist to THC, rather than behaving in a similar way. In December, the ACMD released their review on phytocannabinoids that concluded:

“While the potential risks appear limited, it is not appropriate to recommend rescheduling of delta-9-tetrahydrocanninol-C3 to Schedule 2 of the Misuse of Drugs Regulations 2001, since only therapeutic (medicinal) potential, not proof, has thus far been demonstrated. Such potential can only be established by further research.”

It seems to be that the decision to keep THCV in Schedule 1, for now, is partly due to a study in the 1970s which suggested there may be psychoactive effects and due to a lack of concrete evidence of its therapeutic effects. However, the ACMD did go on to add:

“ACMD recommends that the reasons for the limitations upon research perceived and produced by inclusion of compounds in Schedule 1 of the Misuse of Drugs Regulations (2001) be reviewed in order to determine whether specific recommendations can be made that can safely reduce or remove such limitations and so facilitate research.”

This implies that they will look into ways in which to help facilitate research of schedule 1 drugs. However, Professor Nutt has been very critical of the review, believing this assurance to try and ease the burden on researchers is simply be a fob off and will never materialise. As there are so many barriers to the “further research” required to justify a rescheduling, it will likely not come to fruition without intervention. The ACMD have been contacted but have yet to respond to our request to clarify their position on easing research restrictions.

From an academic viewpoint, as with rimonabant, there is the concern regarding the binding affinities of THCV and all the variants of spice. Some are sceptical that their THCV would be feasible, given that the binding affinities of many types of spice may be higher than these potential antidote targets. Would rimonabant or THCV have a sufficient binding affinity at CB1 receptors to act as an effective antidote to spice, especially the most potent (and therefore more dangerous) variants? However, regardless of this, investigating these could kickstart the research into spice antidotes and lead to an effective antidote to be developed.

Quite apart from the chemical practicalities, there are a number of other things to consider when discussing developing an antidote for spice. For example, for a drug such as this there are plenty of important hoops to jump through before it can be brought to market, including sufficient clinical development, phase 1-3 studies, intervention development studies, evaluation of training of peers, development of practice guidelines and structural development. All these things, naloxone, for example, has gone through.

As rimonabant has previously gone through phase 1-3 trials, it could be possible that not all of these would need to be re-done – perhaps just phase 3 trials again to check the safety of one-off use. Either way, however, it would take years for this to get to market by which time the ‘spice crisis’ could be much worse. In this way, it is definitely not a quick fix and the research and development would have to be conducted in the background whilst other changes are made to tackle the causes of spice use and to help people in recovery.

There are lots of obstacles to overcome when it comes to developing an antidote, with plenty of ongoing funding required, and it’s not clear where all of this would come from. Whilst the government has not offered this funding, no one else has either. That said, if the funding was granted, there is nothing stopping Professor Nutt, or anyone else interested in this, from developing a licensed medicine to act as a spice antidote. Having said this, if someone wanted to develop Rimonabant for this purpose, it would be necessary to involve Sanofi in the process as they would not be able to produce a product for market without them.

On the other hand, whilst Sanofi own rimonabant, there are plenty of other CB1 antagonists, with the potential to carry out a similar function, that could be investigated without their cooperation. So if the two mentioned here are proving difficult to look into, researchers should keep an open mind as to what they can investigate.

Another potential obstacle in using a spice antidote to help people and prevent deaths is the paramedics and treatment services themselves and whether there would be enthusiastic uptake of the usage of the antidote. Many treatment services are resistant to naloxone, for example, even though it saves many lives every year, due to the sheer cost and lack of funds. This could end up being true for a spice antidote too, especially considering the demographic of people it would help and the general apathy that the public have for them.

Another thing to consider is that even a well-developed effective antidote would be of limited utility as a solution to the ‘spice crisis’, as it does not address the route of the problem. They are not going to stop people taking spice or help people get out of the spiral of addiction. Might it be better to focus on the causes of the spice crisis? However, whilst it may be wise to be sceptical, it could definitely help address the immediate harm and prevent drug-related deaths in the years to come and at the very least it is an interesting and worthy area of research.

Overall there has not been a great deal of effort put in to research and develop antidotes for spice, with the government being dismissive at best. Even if neither rimonabant or THCV are ultimately the answer, they may be a good starting point for developing a new drug that would act as an effective antidote and research is obviously necessary for this to happen. So even sceptics about the utility of these drugs, must surely admit that this research would be helpful. Naloxone has saved thousands of lives over the years and as the numbers of people taking spice and experiencing serious health risks as a result increase by the day, we need to do something to help.

Obviously developing an antidote is not the be all and end all – far more needs to be done to help the homeless and prison populations, and it is by no means a solution to the problem. But it could end up saving lives and giving people a second chance and what is more worthwhile than that? If the government truly cares about the people affected by spice they need to prove it and show at least some interest in whether they live or die.

Words by Abbie Llewelyn. Tweets @Abbiemunch.