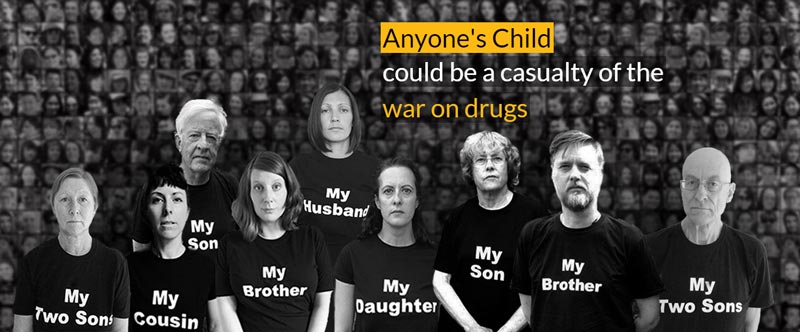

Launched in April 2017, Transform’s ‘Anyone’s Child Mexico’ campaign enables victims of the country’s devastating drug war to tell personal stories via a free telephone line. Voices of pain, anger, fear and courage pervade the poignant anecdotes. The innovative way in which campaign coordinator Jane Slater has collated audio, visual, and textual content (in the form of individual testimonies, infographs, statistics and educational resources) to create the idocumentary, provides global exposure to an issue widely and conveniently ignored by both domestic and foreign audiences.

Photo – http://anyoneschild.org/mexico/

The extent to which the campaign can be regarded as a success, however, will depend on its ability to influence public opinion. In short, can the ‘Anyone’s Child Mexico’ campaign engender a judicial rethinking whereby policymakers begin to design progressive drug policy grounded in science, compassion, and human rights? And can we as a human collective begin to realise the shared goals of improving public health, protecting young people, reducing crime rates and enhancing the effectiveness of governmental expenditure?

The i-doc begins by providing relevant political context and shocking statistical evidence of the devastating effect of President Calderon’s catastrophic misjudgement in militarising Mexico’s domestic drug policy in 2006. For example, reminders of the 150,000 murders and the 310,000 victims of forced displacement highlight the indelible damage caused by insistence on a feckless ‘tough on crime’ approach that, since its inauguration at the UN convention in 1961, has not come close to its stated aim of a ‘drug-free world’.

The i-doc’s first chapter, titled ‘Waiting With Love’, exposes viewers for the first time to phone line audio recordings of accounts from families of drug war victims. Strikingly, the callers’ use of collective pronouns, such as ‘us’, ‘our’ and ‘we’, underline the i-doc’s most prominent theme: “shared responsibility”. Whilst the accounts come from callers of different genders, ages and socio-economic backgrounds, as leading drug policy reformers Michelle Alexander and Bryan Stevenson argue, the most severely affected are society’s most vulnerable and marginalised people. The testimonies are situated against a backdrop of contrasting images, including a heat map, various crime scenes, mass grave excavations, depictions of family unity, and photos of absent sons and daughters (used during missing persons appeals). The especially evocative sight of the Mexican flag, which elicits contrasting feelings of pride and shame, reminds viewers of the nationwide scale of the crisis.

Photo – http://anyoneschild.org/mexico/

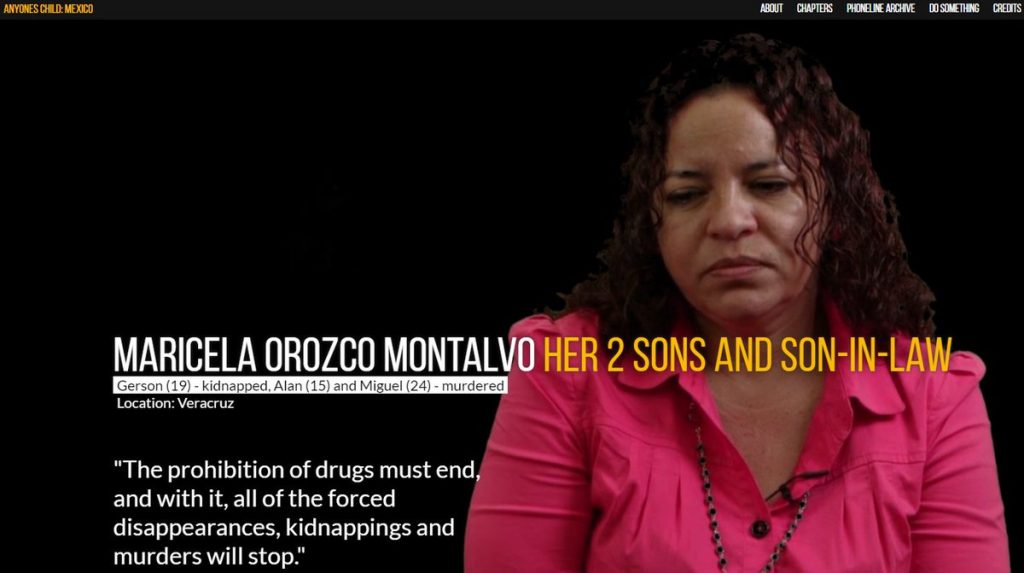

Moreover, the poignancy of the audio clips is accentuated by the inclusion of the names, ages, interests, professions and, most harrowingly, final locations of the countless murdered, kidnapped and disappeared Mexican people. This realistic characterisation works on two levels: Firstly, for victims’ families, the online identification of missing persons provides a sense of renewed hope for the closure and dignity that they desire and deserve. Secondly, the online campaign provides victims’ families with a powerful platform from which to awaken a global audience to a domestic injustice. Pained and plaintive voices of those directly affected by Mexican drug policy provide a contrasting rhetoric to the populist ‘war on drugs’ message which pervades current policy. This effective juxtaposition will continue to reach viewers previously disinterested in reform and will, eventually, catalyse rational, evidence-based debate.

“We are reminding the Mexican government that they have a debt,” says Araceli Rodriguez Nava, who lost her 24-year-old son (a police officer), before declaring a “humanitarian emergency”. In ‘Nowhere To Turn’, the i-doc’s penultimate chapter, the tone of the testimonies becomes pejorative as victims’ families elucidate the causes and consequences of Mexico’s punitive, prohibitionist approach. The issue of widespread institutionalised injustice manifests as sordid police incompetence, brutality and impunity; topics corroborated outside of the i-doc by cop-turned-reform-campaigner Neil Woods and explored further by drug policy scholar Roberto Saviano. Testimonies attest to how endemic corruption of the nation’s institutions constitutes the most significant obstacle for seekers of justice. This in turn leads to debilitating and poisonous mistrust between civilians and law-enforcement that complicates the goal of community cohesion.

Photo – http://anyoneschild.org/mexico/

The final chapter, titled ‘A Perfect Solution’, generates space for families of victims to speak out in order to frame the debate for future drug policy reform. The useful inclusion of links to definitions of relevant drug reform terminology provides viewers with an important opportunity to clarify meanings and avoid misconceptions. For example, the i-doc highlights the reality that, by removing black-market profit incentives, regulation is tougher on crime than prohibition. The linked definitions constitute an especially well-considered feature if the public are to engage in sensible discussions about legislative reform and if lawmakers are to construct appropriate regulatory models that will engender harm reduction, increased public health and stronger communities Ultimately, the outcome of the debate must guarantee a safer world for everyone, but especially for young people and families, so that fewer parents have to count the years since they last hugged their daughter or celebrated their son’s birthday. In a subtle but deliberate return to the theme of “shared responsibility”, the i-doc concludes with an invitation to join the campaign, the conversation, or both. On the campaign’s home page, viewers are implored to tweet a politician to persuade them that now is the time for a meaningful, evidence-based regulatory model that controls drugs, and to find a legal solution that genuinely guarantees the safety of everyone’s family members.

The Anyone’s Child Mexico campaign represents a simultaneously emotive and provocative platform against disingenuous policy-makers who continue to an eschew common-sense approach to drug policy reform. The i-doc’s extensive audio catalogue, engaging aesthetics, and varied media content provide families wrecked by the drug war with an opportunity to educate a global audience about the social and political causes and consequences of a blatant injustice. The timing is significant: during next year’s presidential election, over 3000 local and governmental positions could change. As such, the period between 2018-2021 represents a window of opportunity for incremental legislative progress, a belief strengthened by the fact that, at present, 36% of the Mexican public support cannabis regulation. Ultimately, the true mark of the success of the ‘Anyone’s Child Mexico’ campaign will be the proportion of the remaining 64% of Mexicans who can be persuaded to countenance drug policy reform by recognising that it could be anyone’s child.

Matthew Wood – @Mattywood91