“Any questions?” I ask, as I conclude a one hour drug awareness session to a packed sixth form common room. The projector next to me is beaming a POV shot of a roller coaster onto the wall with the Bill Hick’s quote “Life is just a ride” in bold underneath it.

I take a swig of my water bottle and wait for one of the obligatory awkward questions that follow talking to this age group. A lone hand pops up from the back and I nod his way, betting that from his cocky smile he is going to ask me the second most popular question at the end of any talk; Have I ever smoked weed or taken heroin? Instead he goes for number one; “So you said that alcohol is one of the most dangerous drugs around right… like… worse than cannabis… so if pretty much everyone drinks, what’s wrong with smoking weed?”

“Well… It’s not quite as simple as that”, I reply.

Talking to young people about drugs can be one of the most rewarding elements of drug treatment. Standing in front of three hundred young people and giving them a message that has the potential to change the way in which they understand drugs is daunting, yet exhilarating. I have always felt such talks to be a real privilege and something that carries an enormous amount of responsibility. As drug education is so lacking in schools, many young people get little more than a one hour assembly to learn the truth about drugs, free from the bias that comes from family, friends and the media.

Despite the rewards and short lived fame as you walk to work past a local school and have kids point and shout “You’re the drugs man!” (that one certainly raises eyebrows among parents dropping off their kids) the role comes with a huge risk. If such talks go wrong, young people can quickly create justifications for problematic use, which in a system that provides so little room for drug education is extremely problematic.

The question asked of me in the sixth form common room is both typical and challenging. Professor Nutt’s work highlights the harms of alcohol and is widely known both academically and in popular culture. It is hard to deny that alcohol is more harmful than cannabis. Unfortunately, the complexity of cannabis in the UK means the accuracy of this statement becomes somewhat problematic.

To highlight the issue, the first question I ask any cannabis smoker is: “What kind of cannabis are you smoking?” The typical response: “Well, whatever I can get really, don’t know what type it is… it’s just weed”. Most young people I have encountered are blissfully unaware of the different strains of cannabis that exist, and even if they are knowledgeable on the subject, they simply buy whatever a street dealer has in. This is a major issue and one which I believe contributes to the increasing number of cannabis presentations in both treatment and mental health services.

In reality there are estimated to be around 779 different strains of cannabis all of which contain different levels of THC (Tetrahydrocannabinol) and CBD (Cannabidiol), both of which have quite distinct effects. The truth is that young people (along with most of society) do not appreciate the complexity and variety of these 779 strains and the diverse effects they can have. There is a growing body of evidence that cannabis with high levels of THC (Skunk) impacts the development of ‘neural pruning’ in a young person’s brain and most certainly affects their concentration and engagement in education.

I describe the lottery of black market cannabis procurement to be like walking into a bar and ordering a pint of alcohol. Once ordered, the bartender grabs whatever alcohol is nearby and serves up a pint, which you merrily consume without questioning the ethanol content. As you can imagine drinking in this way would be irresponsible, but it is essentially how cannabis is procured on the black market. Typically speaking, young people buying cannabis have no idea of the THC content and rarely have the strain knowledge to appreciate the impact skunk can have on their wellbeing. This lottery method of procurement is dangerous for people of all ages but none more so than those of a young age with limited education or awareness of cannabis and THC.

Unfortunately educating young people on this issue seems pointless and I often feel like I’m fighting a losing battle. No matter how aware young people become of the issue, the fact remains that most of the cannabis sold on the streets of the UK is high in THC content and if that is all the dealer is selling that’s what they will go with. Although the dark web offers alternative methods of procurement and choice, this is hardly a conversation an ethically sound drugs worker can have with 300 school children, (imagine the Daily Mail headline on that story). The system presents the problem and no amount of educating young people can change it.

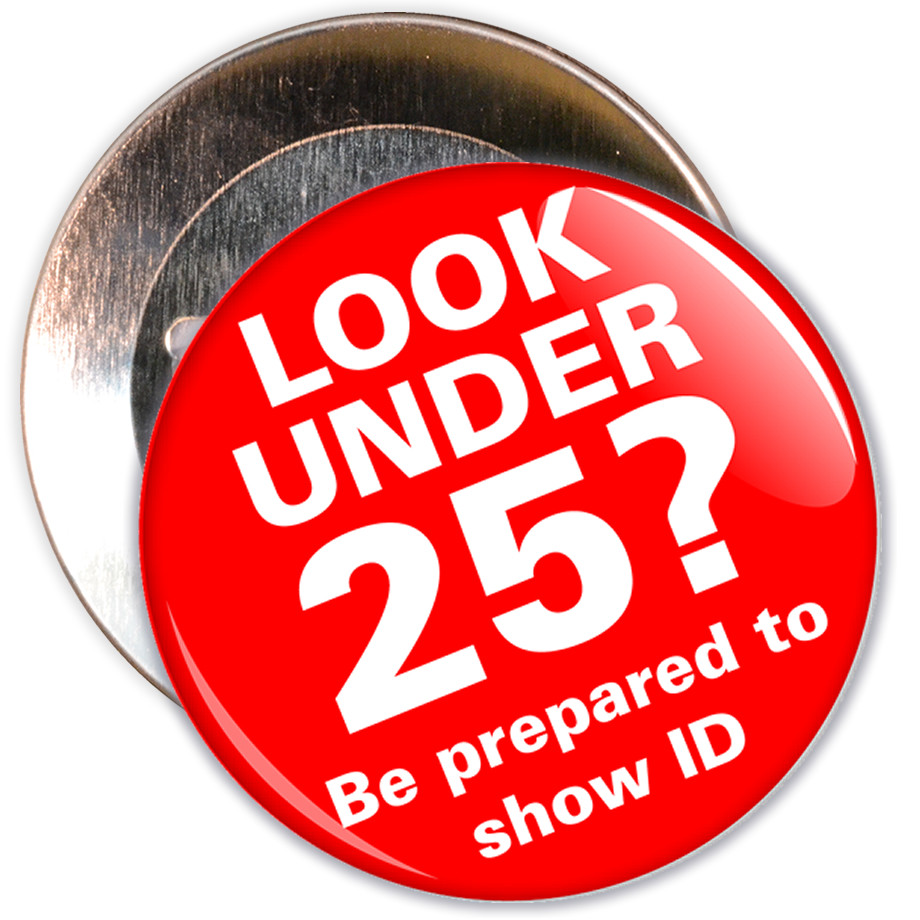

As the young person pointed out in the talk, many people view alcohol as more dangerous than cannabis and use this argument as justification for their own use. Again, the reality is far more complex than a simple scale of harm. There is a great deal of evidence spelling out the harms of alcohol. Yet the key is that alcohol exists in a regulated market where a user can negotiate a relationship with the drug and we can attempt to restrict access to under 18s. Every drink also comes with an ethanol percentage by which a user can seek a measurement to reach the desired effect. With cannabis, we do not have this luxury, and the truth for young people in the UK is that they can access cannabis far easier than they can alcohol. A local dealer is much easier to persuade than a shop assistant wearing a ’Look 25’ badge.

Whilst alcohol is in many ways more dangerous than cannabis, this should not disperse from the reality of the potential harm that cannabis use may cause. The point I made to the young person in the assembly is that a problematic relationship with any drug is by its very nature problematic. Although regular use of alcohol may be more dangerous for young people, it does not detract from the fact that so too is cannabis if abused, especially if its is Skunk, and even more so at an age where the brain is still forming and engagement in education is paramount.

The hardest element of drug education is often sifting through and explaining to young people all the bits from our current model of illegalisation that don’t make any sense. It would be much easier to educate if we didn’t have to do so within a model that lacks a clear message and instead protects them from harm via regulation and education. Even the police have given up trying to enforce such a system, which only adds to the inconsistency of such models. In our locality, when officers have caught young people with cannabis they have simply asked them to attend our service for ‘a chat about it’, no paperwork, no arrest and no clear message.

The fact that cannabis is not policed appropriately, discussed adequately in education, or regulated effectively like alcohol, means an immensely confusing picture emerges for young people to decipher. This too becomes exceptionally hard to explain at the front of an assembly hall. The message our legal framework gives is full of hypocrisy; alcohol is more dangerous than cannabis but legal, cannabis is a class B drug but you won’t always get in trouble if caught by the police, and cannabis is more dangerous now because its illegal.

It is time for treatment services to speak more openly with policy makers about the confusion and complexity that occurs on the frontline. Young people are forming problematic relationships with cannabis due to its illicit nature and availability, and while harm reduction is a great way of helping young people manage their relationship with cannabis, if the only strains on offer are skunk, what options are left on the table? Even the ‘war on drugs’ isn’t even a war anymore, as the police can’t afford it in terms of time or money. It is time we looked closely at the confusing messages illegalisation gives and for policy makers to think critically about the options available.

The Sixth Form assistant head comes over to me at the end of the talk with a concerned frown on her face. “It’s not that bad alcohol is it? I mean, it doesn’t send you mental or anything, does it? I have a few glasses a night and it hasn’t hurt me! The Government would just ban it wouldn’t they if it was that bad?!”

“Well… It’s not quite as simple as that”, I reply.

Read Part One of The Secret Diary of a Drug Treatment Worker