Moments before we go live, a make-up technician leans towards a large expanse of orange flesh, and, for the third time that day, daubs away the crummy residue of a hastily-gobbled Twinkie. As she leaves (with a swish of her skirt but premeditated swiftness), the owner of the visage compulsively flexes his fingers. Old habits die hard, but he remains stationary. The hypnotist on his PR team has been coaching him for months not to grab people’s pussies and they’re about to go live on air at the White House… Lights, camera, morally and intellectually bankrupt action: “We’re becoming a drug-infested nation,” says President Donald Trump, glancing at his script. “Drugs are becoming cheaper than candy-bars. And I’m not going to let it happen, any longer.”

Trump is, unfortunately, a prominent figure who forms part of the international context in which, a day earlier, a smaller-scale but much more sophisticated, pertinent and constructive discussion took place at the London School of Economics and Political Science. The LSE Ideas event (which you can watch and listen to in full here) was chaired by Dr Mary Martin and featured Dr John Collins, Executive Director of LSE’s International Drug Policy Project (IDPP), Professor Lawrence Phillips of LSE, Dr Joanne Csete of The Lancet Commission on Drug Policy and Colombia University, and Dr Michael Shiner, Head of Teaching for IDPP. Together, they outlined possible “Drug Policies Beyond the War On Drugs,” based, in direct contrast to Trump, on a nuanced and carefully acquired academic understanding of the issues at stake.

The ‘War on Drugs’ is a Discredited Strategy, but Stigma Still Kills

Trump denounces “drugs” (which as Prof Toby Sneddon discusses, is a blanket term with a long history of being deliberately misleading, and furthermore one which doesn’t differentiate between the all-too-often lethal opioid substitute fentanyl and the -not as yet lethal- prostrate-related drug Finasteride which Trump abuses to grow his hair) from a platform of immense power. Nevertheless, as evidenced throughout the discussion at LSE, he’s a sagging balloon exhaling stale stigma pertaining to long-since morally condemned and academically discredited lines of thought.

But, whilst his “drugs are becoming cheaper than candy-bars” remark is so abstruse that one could be entirely forgiven for wondering if Trump has been candy-flipping, a tried and tested anthropological strategy forms its basis. He is releasing a vintage brand of hysteria out into the world like a titan: he knows that it will whip up an anti-drugs media frenzy afresh, directly influencing the decisions of politicians worldwide and retarding the progress of drug policy reform.

As Shiner explains in his examination of cannabis’ shifting classification in the U.K. and our Home Office’s deference to The Daily Mail, the mainstream media serves as policymakers’ “barometer for public feeling” about drugs. Paradoxically, and more disturbingly, the inverse is also true: the media is as close in function to an artificial weather simulator as it is to a barometer. When it promulgates hysteria, it subliminally etches factually unfounded but frustratingly dearly-felt beliefs about “drugs” into the hearts and skulls of its followers, beliefs which politicians then purport to “measure” by following the press. (A tendency which has caused social-satirist Charlie Brooker to dub the media “the most dangerous drug” of all.)

Nevertheless, the mainstream media reliably renders politicians scared, or – as Shiner discusses, in the case of briefly reclassifying cannabis from B to C as the Labour Government did in 2004, brave enough- to make potentially unpopular drug policy changes. Trump’s supporters might argue that his bombastic “candy bar” comment about the price and prevalence of drugs was not intended to be taken literally. Nevertheless the consequences of the remark will be real; the policymaking it inspires will cost millions their lives, causing drug-related deaths worldwide.

This is clearly illustrated by Csete, who, deliciously candidly, describes her visit to the U.K. to participate in the discussion as a welcome respite from “an asylum run by a hyperventilating, braying huckster, (if only that were a metaphorical description!)”. Leaving aside the idea of making changes to the classifications of various controlled drugs, she illustrates how personal prejudices can and do result in politicians blocking harm reduction measures with lethal consequences:

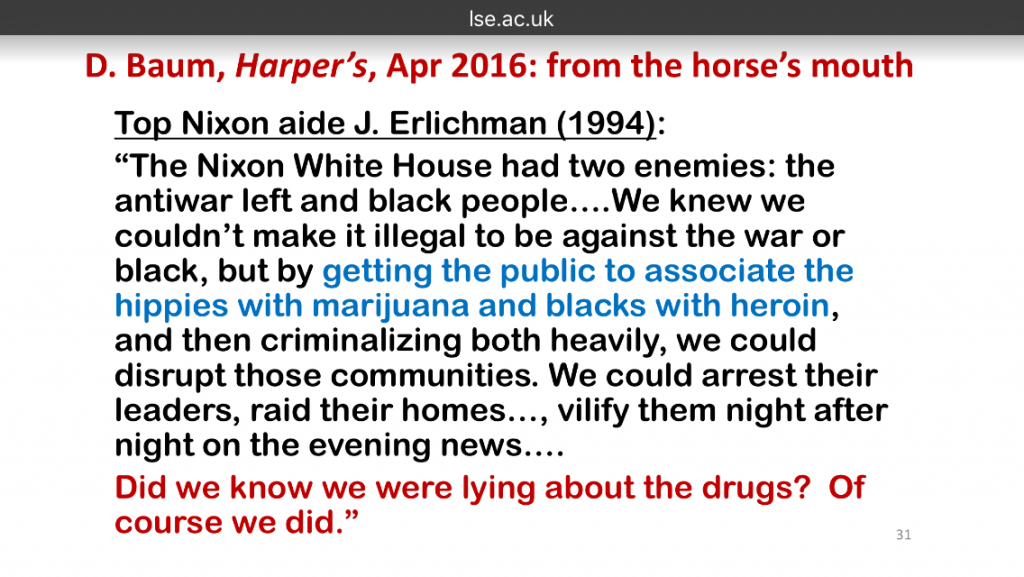

Charges of Crimes Against Humanity are literally being brought against Trump’s Vice President Mike Pence, who caused the most severe outbreak of HIV in North America in recent years with his closure of the Planned Parenthood centres. These had previously been the sole providers of HIV-preventative measures in Indiana, such as needle-exchange services. Figures speak for themselves, so Csete reveals the recent positive impact of a single US safe-injection facility: 3000 overdoses, no deaths and no brain damage, “because harm reduction works.” As well as showing how Trump’s “neo-Nixonian” endorsements of prohibition will exacerbate existing drug-related problems, she goes one better, and flags up their overtly racist origins:

Findings from the Frontiers: LSE’s International Drug Policy Project

The LSE Ideas event has an importance far beyond being a fantastic, Tramadol-like ideological panacea to the bizarre and perplexing reality of Trump’s presidency. Collins points out at the outset of his presentation that the “War on Drugs” is already an “internationally discredited strategy.” He illustrates this with a show of hands: “Who thinks the war on drugs has been a success?” Absolutely no one. “Drug Policies Beyond the War on Drugs” is categorically the only one of the two happenings featuring thinking relevant to the future of global drug policy.

The Expert Group’s landmark study “Ending the Drug Wars” (2014) made waves by advocating that drug policies should informed by research from an academic framework. One of the top ten policy studies by a think tank worldwide, Collins describes its provocation of a “massive normative shift” in the public perception of the War on Drugs. It stimulated a much-needed flurry of enlightened articles decrying current drug policy’s tangible harms.

In their next report, they focus on alternative policies. “After the Drug Wars” (2016) advocates deprioritising the prohibitionist strategies that have caused so much harm, and implementing Sustainable Development Goals (STGs) – initiatives that focus on protecting public health, integration and sustainability. The report was signed by 6 Nobel Prize Winners, including the Colombian President Santos. This calibre and quantity of endorsement demonstrates that those who have experience of policymaking are keen to be guided by academic thinking, specifically of the kind which takes place outside the ivory tower.

Policies need to be made based on case-studies of the people whose real lives they affect. To make this happen, the IDPP are making eye-opening journeys down dirt roads (“it’s generous to call it a road,” says Collins, alluding to its barrenness and geographical remoteness from any social services) to channel the lived experiences of Colombians whose livelihoods have been wrecked by crop-spraying directly into the academic discourse that will eventually inform the local drug policies that will govern them.

“In some cases, we don’t know what to do, but we know what to stop doing.”

In many parts of the world, Collins explains, current drug control measures are so devastating to communities, that, even just to deprioritise them would constitute an active and dramatic improvement – a vital step before the implementation of new, more holistic protocols can be strategized. Collins offers us some examples of the policies that -with their incredibly evidential harms- the IDPP have identified most pressingly need to be eradicated from future drug policy discourse.

Rather than breaking up the structure of drug-trafficking cartels, the IDPP’s research in Mexico reveals that decapitation (state-sponsored removal of the heads of the cartels) leaves the hierarchy intact, with the subordinates struggling to assume power. This reliably creates a hydra effect, where two cartels spring up in place of one, each claiming a separate territory and thereby spreading the inevitable violence that pertains to two warring cartels across a greater area.

There’s no correlation between criminalization and consumption, so excessive policing simply raises the incarceration rate, and unnecessarily tars more people with criminal records, greatly increasing the chances of their participation in further, and/or non-drug related crime.

Finally, Collins outlines the various disadvantages of spraying crops as a means of eradicating the supply of coca in Colombia. The chemical used is “extraordinarily expensive, ineffective, pollutes the water supply and is a carcinogen.” Furthermore, as a biologist who examined the area observed, it has made it “more effective for coca to grow, as they’re eliminating the competition”! Supply eradication simply displaces the location of the source: “you focus on reducing the supply in Colombia, and [an identical incarnation of the cocaine trade] pops up in Peru and Bolivia.” Interestingly, Collins terms this displacement “the balloon effect”; as Prof David Nutt elucidates in his 2012 popular guide to drugs and their various effects, there is no place for balloons full of hot air in the development of sensible drug policies.

The abandonment of these actively damaging measures will allow politicians to begin pursuing SDG’s, such as introducing inclusive, “wraparound” social services for those experiencing drug-related problems. In combination with scrapping these actively damaging drug control measures, a move from prohibition to a legally regulated market is as necessary in Latin America as it is elsewhere, so that the next generation of public services can improve people’s lives most significantly.

Squaring up to Stigma: A Rational Evaluation of Drug Harms

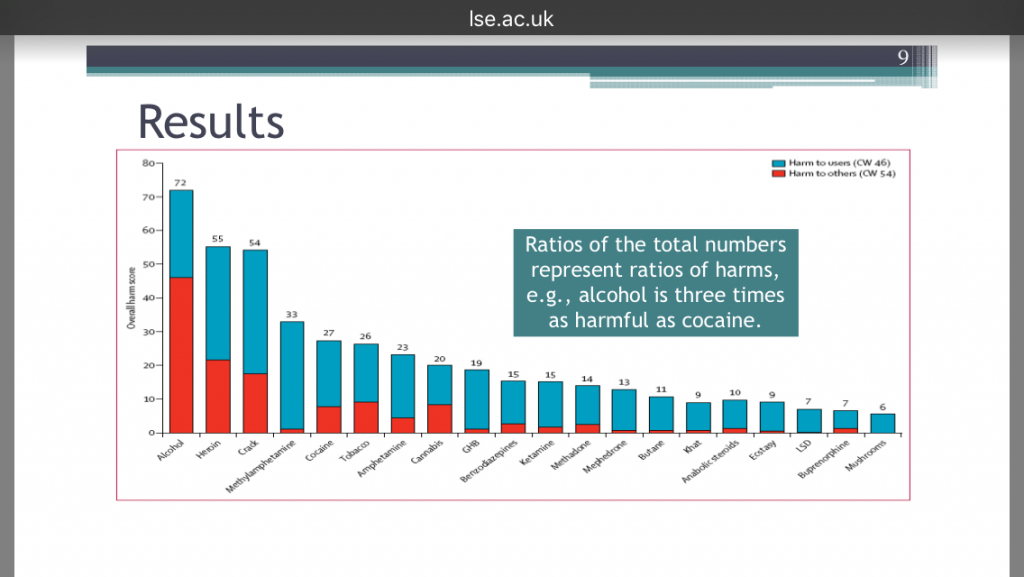

“I know how to turn evidence into policy recommendations,” says Lawrence Phillips, Emeritus Professor of Decision Making at LSE, who presents “An MCDA framework for evaluating and appraising government policy for psychoactive drugs.” First, Phillips explains how individual drugs can be evaluated for harmfulness. He is author of the pivotal and much cited “Drug Harms in the UK: a multicriteria decision analysis (MCDA)” (2010) conducted on behalf of the Independent Scientific Committee on Drugs with David J. Nutt and Leslie A. King.

“Throughout my career, my wife has often reminded me that I have a touching faith in rationality.” And, as Phillips talks us takes us on a thorough tour of the decision-making formulae behind the ranking system, he certainly inspires one, especially given the discussion’s timing! Twenty drugs were assessed based on 16 harm criteria by the ICSE member and two external mediators at a meeting facilitated over a decision conference. This kind of careful, honest academic rigour feels like the other extreme, in comparison to the panoply of pathologies being pantomimed by a certain individual across the pond. After surveying the 20 drugs, the ISCD ranked them from most harmful (alcohol) to least (mushrooms).

These results clearly suggest that policies should be changed to reflect them. As in the earlier incarnation of this study, which earned Nutt dismissal from his position as the government’s drugs advisor in 2007, alcohol retains its position as the most harmful drug. According to Philips, government-funded healthcare resulting from alcohol specifically, costs each individual U.K. taxpayer £1,000 per year. (Alcohol was also found to be the most harmful overall drug in the earlier incarnation of these results, which, because they failed to corroborate existent policies, earned Nutt his dismissal from his position as Chair of the Advisory Council for the Misuse of Drugs in 2009).

Shouldn’t we ban alcohol too, then?

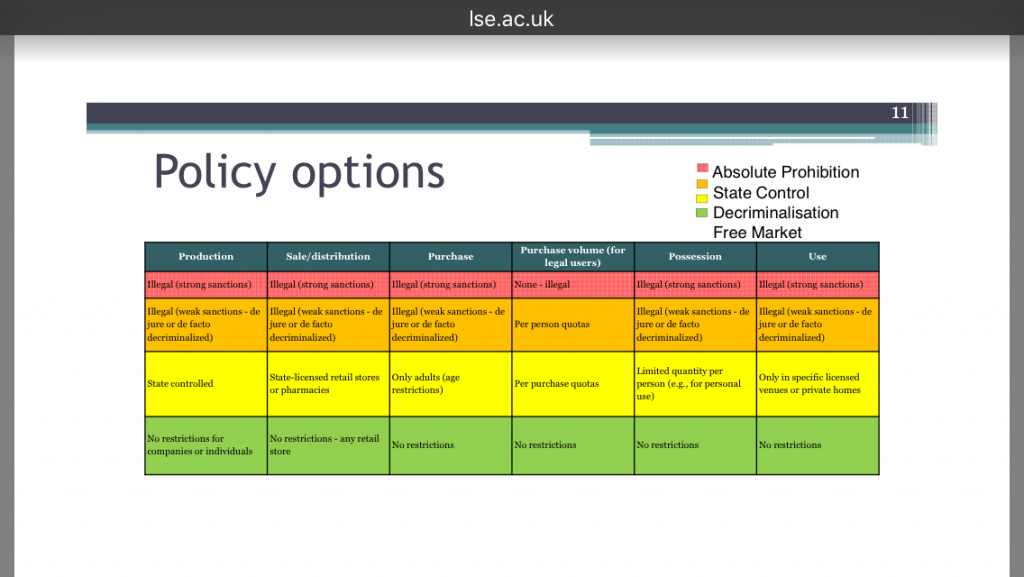

A prohibitionist might jump on this figure and argue, that, if it’s causing so much damage, alcohol, too, should be illegal. They would be, scientifically, wrong. Philips explains the results of more recent work by the Drug Harm Policy Project (2016), undertaken as a collaboration by Nutt’s DrugScience and Frich Gate. Like the MCDA framework for evaluating drug harms, their investigation into which policies suit different drugs is based on a careful decision-making process using a sophisticated methodology.

They used 27 evaluation criteria to decide whether each individual drug’s harms would be most minimised by prohibition (red), decriminalisation (orange), government regulation (yellow), or a free market (green).

That’s “twenty-seven topics to argue about!” And the findings? For every single drug surveyed, the potential for harm was at its greatest with an illegal status. Philips compares cannabis, alcohol and heroin, and the results show that a strictly regulated legal market would most effectively reduce the harms of all three substances.

“We now have a coherent framework for discussing drug policy,” he concludes. It’s just a matter of convincing policymakers to adopt it. Was there a reform bias in the room? Inevitably. However, as Csete’s research into the diverse and disturbing array of treatments currently on offer for drug-users goes on to demonstrate, a reform bias is certainly an improvement on a racial one!

Patients not Criminals: Public Health as a smokescreen in drug policy reform

As in the wake of the “War on Drugs”, most policymakers -whatever their beliefs- approach drugs within a “public health conceptual framework.” However, Csete describes the phrase “patients, not criminals” being “dropped from the mouths of delegates” from some of the countries where the worst human rights abuses are being carried out in the name of protecting “public health.”

The adoption of these words into global drug policy discourse is, she explains, deliberately misleading. Her presentation traces the roots of current “treatments,” back to historic “population control” measures such as forced sterilization, which were designed to reduce the world’s non-white population. Because the “criminal” and “patient” statuses of drug users are often amalgamated, they are all too often involuntarily subjected to the various forms “treatment” can take.

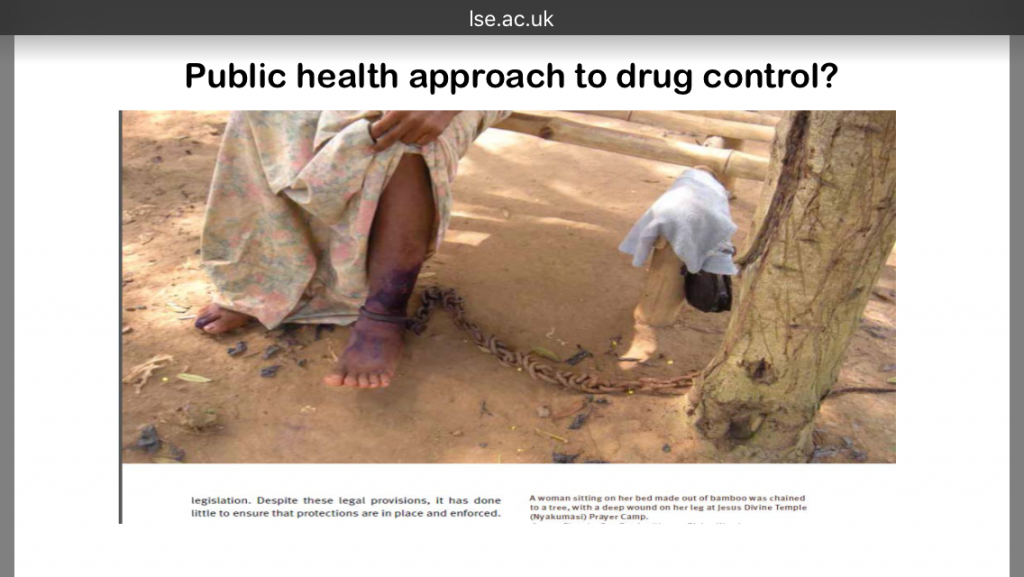

Thanks to the documentative accomplishments of the Human Rights Watch, Csete takes us on a brief photographic tour of some of the atrocities currently masquerading as “treatments” worldwide, which include mass incarceration, forced labour and outright torture. “For what other health-based problem would anyone call chaining someone to a tree and beating them to a pulp “treatment”?” she asks, revealing a glimpse of daily life in a faith-based treatment centre in Ghana.

Going forward, the phrase “treatment not torture” needs to replace “patients not criminals” in drug policy discussions worldwide, to reduce the potential for providers of treatment to gratify their discriminatory inclinations.

Social problems are often several and intricately connected, with drug-related elements being a small part of a whole picture. It is disconcerting that it should be so refreshing to consider that, when people are caught with illegal drugs in Portugal where they are decriminalised, they are met with a range of social service providers. It is not only accepted that they might not have a “problem” but also that, if they do, it might have its roots in “unemployment, or discrimination, or something else entirely!”

Learning from a Foiled Reform: Cannabis Classification in England and Wales

Various small-scale experiments such as the Lambeth cannabis pilot -in which the police of Lambeth did not arrest members of the public for cannabis possession between 2001 and 2002- indicated that decriminalising cannabis throughout the U.K. could have enormous positive benefits. In the first six months alone, police and the public saved a combined total of more than 2,500 hours! There was a 19% increase in arrests of class A drug dealers and all local head teachers to respond to a survey said there had been no increase in cannabis-related incidents in schools; several headteachers said there had been fewer. The Lambeth cannabis pilot was supported by 83% of residents outright or unconditionally. Essentially, drug policy reform was explored extremely successfully in this single London Borough.

It was reasonable of the Labour Government, when reclassifying cannabis from B to C in 2004, to expect these results to be replicated across the country as a whole. However, Lambeth proved too small a crucible to withstand the prejudices and preferred practices of the entirety of the U.K.’s Police Constabulary. In keeping with the idea that there is a complex, multilateral relationship between drug policy making, the attitudes of the population and the media, Shiner delineates how this particular reform was “thwarted,” not, as is usually the case, by pusillanimous politicians, but by the attitudes of the police.

Shiner draws on two 2016 sociological studies on the police, which reveal that a great proportion of them, arresting members of the public for drug possession is part of “a moral crusade.” Cannabis is symbolically important to the police, these studies reveal: it’s how they imagine the tangible success of their job, and experience a sense of achievement. Police are “wedded to the drug war mentality and motivated by operational success on a case by case basis” (Bacon, 2016). Furthermore, “confiscating drugs provided officers with a tangible outcome that eluded them in many other cases” (Bear, 2016).

“As an unwanted, externally imposed reform, the reclassification of cannabis was adapted to reflect the priorities and practices of the police organisation,” explains Shiner. The prejudice-fuelled predisposition of some police to go after members of the public disproportionately for cannabis possession is reflected in the statistics: during the period where cannabis was classified as a Class C drug, 70% of self-reported arrests made were for cannabis possession.

The fact that arresting people for small-time drug possession provides police with a false sense of the importance of their job is exemplified by the Crawley Police, who combine it with another very self-affirming pursuit: uploading their antics to social media. Not only were they famously compelled to return a seizure of poppers which was made under the impression that they were covered by Psychoactive Substances Act 2016, on the day of its introduction (“#nosecondchance #poppersincluded”) but they have also been known to post amateur photography on Twitter on the beat: “enjoying the foliage whilst searching for cannabis smokers; certainly a far better smell.” Perhaps, if like ‘Good Cop Bar War’ (2016) author and UK LEAP chairman Neil Woods, they were to stop looking at the hollyhocks and engage with the reality of the drug-related criminal underworld, rather than concentrating on cannabis possession, they might be inspired to join Law Enforcement Against Prohibition – growing ranks of police worldwide who have experienced the damaging effects of our drug laws first hand and no longer wish to enforce them.

Shiner’s presentation clarifies that -even more so than within society at large- the police force is populated by a significant proportion of individuals who’ve got into the habit of believing “alternative truths,” and have become unused to disentangling learnt prejudices from the bare facts. There will be many challenges, as Collins points out, when we move “from an illicit market to a licit one.” As Shiner elucidates, “reform is not a top-down process, and as such one of these challenges will be working to help dismantle cultural biases which, for many, were once legitimised by our prohibitive drug laws.

For how much longer can stigma stand in the way of rationality?

The press conference at the White House and the discussion at LSE are ideologically opposite in spirit, but nobody should make the mistake of thinking that the two clashing standpoints are equally weighted, or alternatively valid. The problem is not that we don’t have the wherewithal (the researchers, the techniques, cognizance that they are needed) to design feasible alternative policies, it’s that the global intellectual climate has -for so long- not been ready for them. And now, as Csete observes- governments aren’t necessarily funding vital follow-up research.

This discussion conveyed the importance of the work of the International Drug Policy Project, the Independent Scientific Committee on Drugs and The Lancet Commission on Drug Policy and the drug policy reform movement with electrifying clarity. When we “give Donald the warm and energetic welcome [to London] he deserves” (Csete), let’s all protest for prejudice-free policymaking. As Deej Sullivan excellently explains in a recent reconnoitre at the lack of public engagement with drug laws, “have British people forgotten how to protest?”, the repercussions of harmful drug laws affect us all. But, even if you don’t have a particular interest in drug policy, surely we can all get behind the idea that all laws should be made with integrity, and without disregarding, or deliberately trimming away research (Theresa!) by people with an empirical understanding of the issues at stake?

If authentic findings can trump prejudices and inform our next drug policies as fully as they should, then Trump, the belligerently bewildered septuagenarian who has found himself as President of the United States, will be one of the War on Drugs’ last prominent foot soldiers. Any public policy that affects humans should be underpinned by the steadfast commitment to academic integrity which was so pronounced throughout this drug policy discussion from LSE Ideas.

Rosalind Stone is Director of Development for Drugs and Me. She has also written for Psymposia, Talking Drugs, The Stylist and The Londonist. Tweets @RosalindSt0ne