Unsurprising but true: policy documents and treatment interventions developed to tackle illicit drug use do not acknowledge the social benefits, and indeed pleasures of, substance use.

It would make little sense to continue prohibition if there was no industry voice whatsoever to advocate such a message.

In this article we will focus on what this silence around pleasures related to cannabis implies, but our principle points could apply to any illicit drug.

Improving our knowledge of the pleasures of cannabis could provide more balanced public health messages and information. This could in turn improve public engagement, message credibility, and the expectations of those entering treatment. By focusing solely on harms they have lost sight of why so many people start and continue to use cannabis. A fuller understanding of the pleasures and benefits of cannabis use could offer valuable intelligence for public health, treatment and policy.

Treatment

Many people are drawn into drug use by the pleasure drugs offer, both in the short term and the long term. Drugs such as cannabis can enhance many physical and psychological senses. For many this pleasure is maintained through a sense of control, but others unfortunately find that pleasure diminishes and their balance between pleasurable and problematic use tips towards negatively impacting their health and or social lives. It is the latter group who seek treatment.

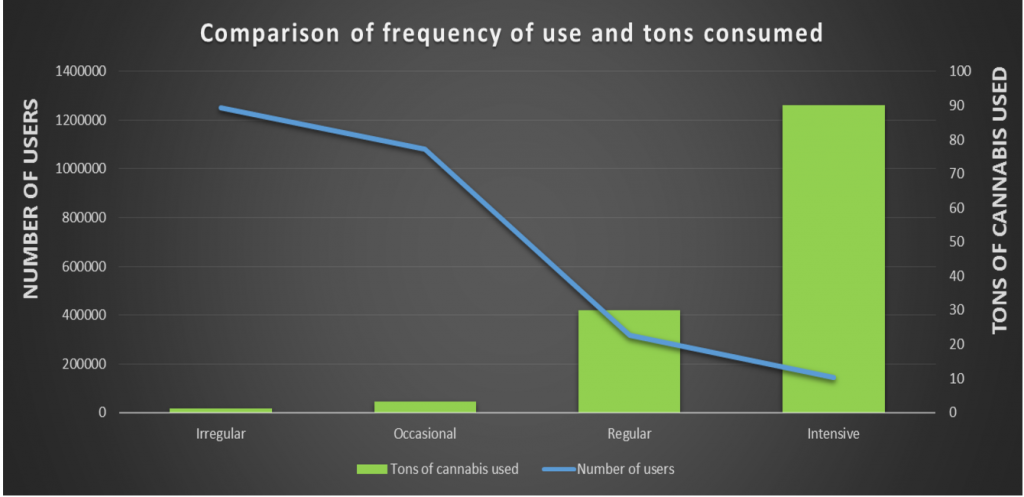

This group are distinct from their peers who continue to gain pleasure from cannabis use or at least abstain if pleasure is diminished. Problematic cannabis use is associated with social stress and psychosis. Immediate benefit rather than long term consequences is prioritised for such people, but they lack the supportive social networks that those in higher socio-economic groups benefit from. Their risk of developing a range of problems, including cannabis dependency, is enhanced by the disproportionately large amount of cannabis they use. A mere 9% of individuals are responsible for consuming 73% of the cannabis available illustrated in the graph below. Some of the more frequent, heavier users of cannabis will be doing so to counter their poor mental health.

‘Irregular’ – Less than once a month

‘Occasional’ – Less than once a week but at least once a month

‘Regular’ – Once a week

‘Intensive’ – Daily or almost daily

Although the advantaged and disadvantaged are able to gain cannabis pleasure in the same way, they have distinct consumption patterns and underpinning needs for pleasure. Both these patterns and needs ultimately lead to differing trajectories when problems arise. However, it is not solely the cannabis that has ‘caused’ the problem, but rather the social disadvantage of exclusion, isolation and poor mental health that preceded exposure to cannabis which provides the toxic mix prompting engagement with treatment.

Strengths, not deficits

Despite the paradigm shift years ago in mental health towards a strengths model, with its focus on an individuals journey, the main drug treatment response to date for all drugs including cannabis is problem focused, and offers a problem orientated suite of interventions.

The first stage of these interventions is assessment, which concentrates on problems associated with cannabis use, as well as basic information about frequency and quantity of use. The assessment stage is key to building a rapport and setting the therapeutic tone of the relationship between client and therapist. Given that therapeutic engagement relies on facets such as warmth, honesty, empathy and openness, it is odd that such a skewed focus – treating an individual’s use of cannabis as a kind of deficit – is taken. The role these components of engagement play in research outcomes have not been acknowledged sufficiently; instead it is the intervention that has usually received research attention.

The evidence-base for the effectiveness of cannabis dependency interventions is equivocal. There is no clear sense that any single intervention outperforms others (Cooper et al, 2015) and engagement is likely to be enhanced by including a more strengths and pleasure balanced exchange. Likewise, interventions are distorted by fixating on problems rather than augmenting strengths with deficits. While treatments such as cognitive behavioural therapy and motivational interviewing might build self-efficacy and affirm positive attributes, they do this solely in relation to compliance with desired behaviour or cognitive change. There is opportunity to negotiate what this desired change might be, but it is largely blind to the existing strengths and current or past pleasures the client has experienced and values. Acknowledging both strengths and pleasure as the individual perceives them is not only critical to building therapeutic rapport, but provides the therapist with crucial intelligence about the individual. In motivational interviewing there is at least an attempt to garner this perspective by employing decisional balance information from the client.

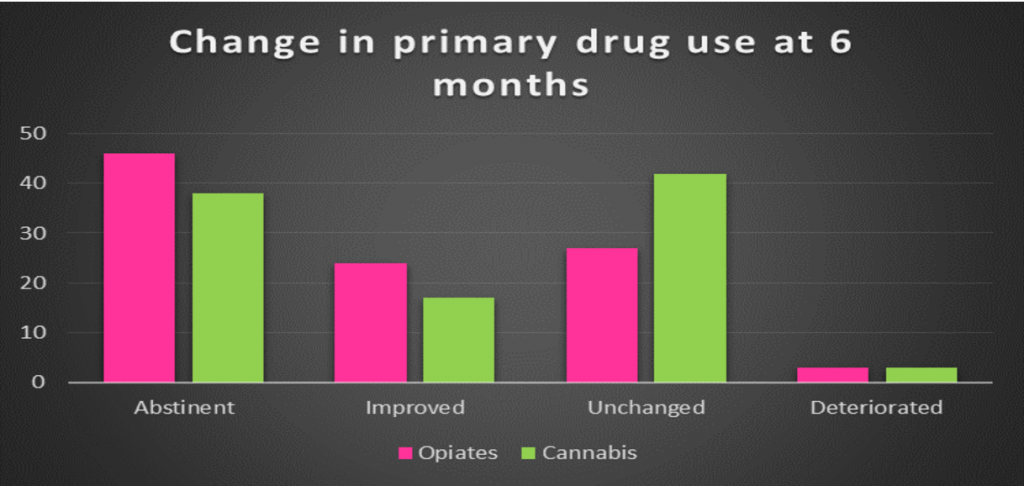

The policy shift from harm reduction to abstinence incentivises a binary measurement of treatment outcomes, where an intervention is deemed successful if the client stops using cannabis and the intervention ‘fails’ when the client continues using or exits treatment prematurely. But for some a more realistic approach would be to calibrate the pleasure / risk balance for an individual client. Compared to their opiate counterparts people whose primary drug problem is cannabis fair less well in treatment illustrated in the graph below depicting the latest treatment data reviews conducted six months into treatment.

If therapists understand what pleasures the client gained from using cannabis, they can then work towards restoring these, either through adapting current quantities and frequency of cannabis use, for example, or by discussing alternatives. Either way an acknowledgement of pleasure and an effort to install this component as part of the intervention is not only more balanced but offers the client hope that the pleasure deficit can be restored.

Public Health Campaigns

The considerable investments made in marketing regulated substances is a testament to the effectiveness the alcohol and tobacco industry place in promoting positive messages about their products. Their funding ability not only dwarfs that of public health but they are more sophisticated and appear more tuned-in to their audience than public health. Although not routinely available publicly, it has been suggested that the alcohol and tobacco industry collaborate by sharing intelligence on strategy. At least they evaluate their marketing efforts, something that is lacking in public health campaigns about substances. Of the limited evaluations published, public health campaigns run the risk of promoting rather than deterring drug use.

Indeed, reducing the stigma associated with treatment and interventions could help engage those with the greatest need.

Perhaps the fear in public health and treatment is that by acknowledging pleasure we are in a way condoning drug use. There is also a sense that highlighting pleasure could contribute to the ‘benign neglect’ of cannabis dependency as a public health problem. Denying pleasure, however, misses an important aspect of an individual’s experience. A persons’ relationship with cannabis is a story that needs to be heard, listening to the good and bad of that experience provides a more rounded view of that relationship.

In treatment, policy and research we’ve been hypervigilant for problems and blinded to pleasure. Balance must be restored.

Mark Monaghan is a Lecturer in Criminology and Social Policy at Loughborough University. Tweets @mpmon

Ian Hamilton is a Lecturer in Mental Health at the University of York. Tweets @ian_hamilton_