The central revelation of the ‘Panama Papers’ is how the criminal, the corrupt, and the cheat hide and move their dirty money. Their approach appears simple: hide dirty money in plain sight, through normal bank accounts, which are owned by companies or trusts that cannot be linked to its real owners. This is made possible by engaging the services of secrecy providers – lawyers, bankers, accountants and other middlemen, whose principal role is to maintain the fiction of the ‘limited liability company’ as a legal person.

A company, once established, can legally trade, transact business, or make and receive payments, even if its real owners are unknown. It can purchase properties, say, prime real estate in central London; buy shares in a listed, publicly-traded company; or invest in profit-maximising portfolios run by fund managers. The sheer magnitude of the abuse exposed by the Panama Papers shows how easy it is for drug lords to register companies and set up bank accounts to enjoy the proceeds of crime, legally. Prime Minister David Cameron has himself effectively admitted that London, with its banks and prime properties, has become a huge parking lot for dirty cash.

The failure of last April’s UN talks on the world drugs problem to recognise the problem of secrecy-for-sale is shocking, to say the least. If the UN were really serious about bringing drug lords to justice and hitting them where it hurt, it could simply have resolved to end the financial secrecy that criminals use to cover their tracks and hide their money. Yet there is no mention at all in the ‘outcome document’ of the UN talks on how secrecy services – so crucial to those profiting from the drugs trade – could be tackled. This is an extraordinary and inexplicable failure.

How it’s done

A month after Mexican drug lord Joaquin ‘El Chapo’ Guzman, kingpin of the Sinaloa drug cartel, escaped from a maximum security prison last July 2015, a branch of a company called ‘Tequila Honor’ was registered in Miami, Florida. The parent firm with the same name was registered a year earlier in Delaware. This registration of Tequila Honor was conducted by an agent, Harvard Business Services Inc., which trades on the website www.delawareinc.com. Its business is to set up corporate entities for clients that it will then not identify. In its brochure, Harvard Business Services states that

“anyone, anywhere in the world can incorporate in Delaware, without ever visiting the state”.

Secrecy is presented as the agent’s unique selling point:

“The only circumstance under which we will divulge company information is when we are forced to do so through legal proceedings.”

Much is known today about Tequila Honor LLC because Mexican intelligence services are said to have been already on the lookout that the drug lord was looking to invest financial resources in a company with legal operations in Delaware. Hence, the company registration was monitored closely by Mexican prosecutors. In February 2016, after Guzman was recaptured, the prosecutors also invited Mexican actress Kate Del Castillo to testify on the financial links between the company and the drug lord. The actress appeared in adverts as the public face of Tequila Honor, and was widely reported as El Chapo’s friend.

Del Castillo denied the allegations. In a press statement, Tequila Honor also denied wrongdoing, pointing out that the company has not been called to testify, emphasising that it “intends to cooperate with authorities as needed”. Nothing is still known about the identity of the real owners of the company, except that “they are a group of brand development experts focused on bringing an excellent product to the market”. News reports also did not identify the bank or banks with which Tequila Honor had opened accounts, or through which it transacts its sale of tequila stocks to its distributors in the US (listed in its website). To date, Tequila Honor is a legitimate capitalist enterprise – there is no evidence that the company does, or does not, have financial ties to El Chapo.

[Watch] Regulate. But How? – Our first VolteFace debate on how the UK should regulate cannabis

This case demonstrates the near impossibility of conducting due diligence or know-your-customer checks on each and every new company registration. Each year, it is estimated that over two million new companies are born (registered) in the US. The UK, with its overseas territories and crown dependencies (e.g. British Virgin Islands, Cayman Islands, etc.) is not far behind. Agents like Harvard Business Services, or the now more famous law firm Mossack Fonseca, are required by law to know who their customers are. When ‘offshore companies’ (i.e. those registered ‘offshore’ in Delaware, the Cayman Islands, etc.) open bank accounts, banks are also required by law to make due diligence checks, and to submit SARs (Suspicious Activity Reports) if they suspect anything suspicious or do not know where the funds of their clients are coming from.

However, as pointed out by the economist Jeffrey Sachs, the sheer volume of registrations makes it impossible to do proper due diligence. Mossack Fonseca has registered over 300,000 companies in its 40 years of operations. With 250 working days in a year, this means conducting background checks, collecting paperwork, asking questions or writing profiles about company directors at an average of 30 companies a day. That the firm could do due diligence on over 300,000 firms, Sachs said, “is beyond ludicrous”. Harvard Business Services, a much smaller firm, reports to have registered over 149,000 companies in 30 years of operation, or an average of 17 a day. Clearly, the Panama Papers exposed only the tip of the iceberg.

The complicity of banks

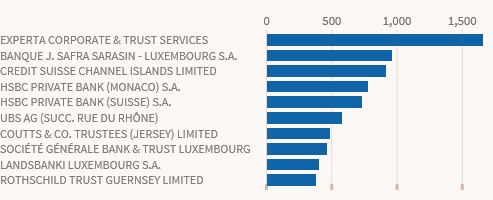

The Panama papers also revealed that Mossack Fonseca had worked with “more than 14,000 banks, law firms, company incorporators and other middlemen to set up companies, foundations and trusts for customers”. More than 500 banks, their subsidiaries and branches, are reported as having “registered nearly 15,600 shell companies”. The table with “the 10 banks that requested the most offshore companies for clients” is presented below:

In this table, ICIJ focused attention on the biggest bank in Europe, saying that “HSBC and its affiliates created more than 2,300 (offshore companies) in total”. This comes as no surprise, because on July 17, 2012, the Permanent Sub-Committee on Investigations (PSI) of the United States Senate had already exposed HSBC as a key conduit for illegal proceeds associated with organised crime.

[READ] Follow The Money – Drug money keeps the global financial system afloat, Harry Shapiro explains

The PSI investigation came about because there was concern, among others, that drug traffickers unable to deposit large amounts of cash in the US due to anti-money laundering controls were transporting US dollars to Mexico to arrange for bulk deposits in Mexico. Once inserted in the Mexican financial system, Mexican banks – in this case HSBC affiliate HSBC-Mexico – could easily insert it back into the US financial system through its correspondent bank account with HSBC-US. The PSI reported that in 2007 to 2008, HSBC-Mexico was the single largest exporter of US dollars to HSBC-US, “shipping $7 billion in cash to HSBC-US over two years, outstripping larger Mexican banks and other HSBC affiliates”. US law enforcers were of the opinion that HSBC-Mexico’s “bulk cash shipments could reach that volume only if they included illegal drug proceeds.”

Solutions

No charges have been filed against Mossack Fonseca. They have been vehement in asserting that they have not broken any law. Equally, many other agents like Harvard Business Services continue with business as usual. Despite the US Senate investigation, HSBC was not prosecuted – the US Department of Justice, in a deal reportedly penned by now Attorney General Loretta Lynch, accepted a public apology from the executives of HSBC Group and received a fine of $1.9 billion from the bank.

The problem really is that no laws are being broken. If laws have been broken, the best response would be enforcement, prosecution, and eventually conviction and the confiscation of assets. But the global armies of imaginative criminals, aided by professional lawyers, bankers, and accountants, are too clever to be breaking the law when hiding or moving money. With no one being prosecuted because no laws are being broken, the system that makes crime profitable continues.

What is baffling is that the solution is simple and inexpensive – require new companies to declare under oath their real, beneficial owners, identified by their unique passport number or driver’s license, and put the information on a publicly accessible register (i.e. a database searchable online with no fees charged for access). In other words, company registrations will continue, but secrecy of ownership will be removed. In the absence of a ‘silver bullet’, public registers of real owners are the best that we could have in dealing with the scourge of secrecy for sale.

The UN General Assembly Special Session held in April completely failed to respond to the new information confirmed by the Panama Papers leak. Such failure of the international community to deal with problems like secrecy for sale only reinforces the opinion that the systems in has in place are simply not fit for purpose.

Eric Gutierrez is a Senior Adviser on Accountable Governance and author of the report Drugs and Illicit Practices: Assessing their impact on development and governance.