An exhibition by Estonian artists KIWA and Terje Toomistu brings Soviet hippies straight into the lair of East London hipsters.

The Red Gallery in Shoreditch has been hosting the exhibition Soviet Hippies: 1970s Estonian Psychedelic Underground Culture in its small space with bare walls, adorned only by photographs, screens and shelves displaying vinyls by Soviet Estonian bands and Led Zeppelin records with Russian titles.

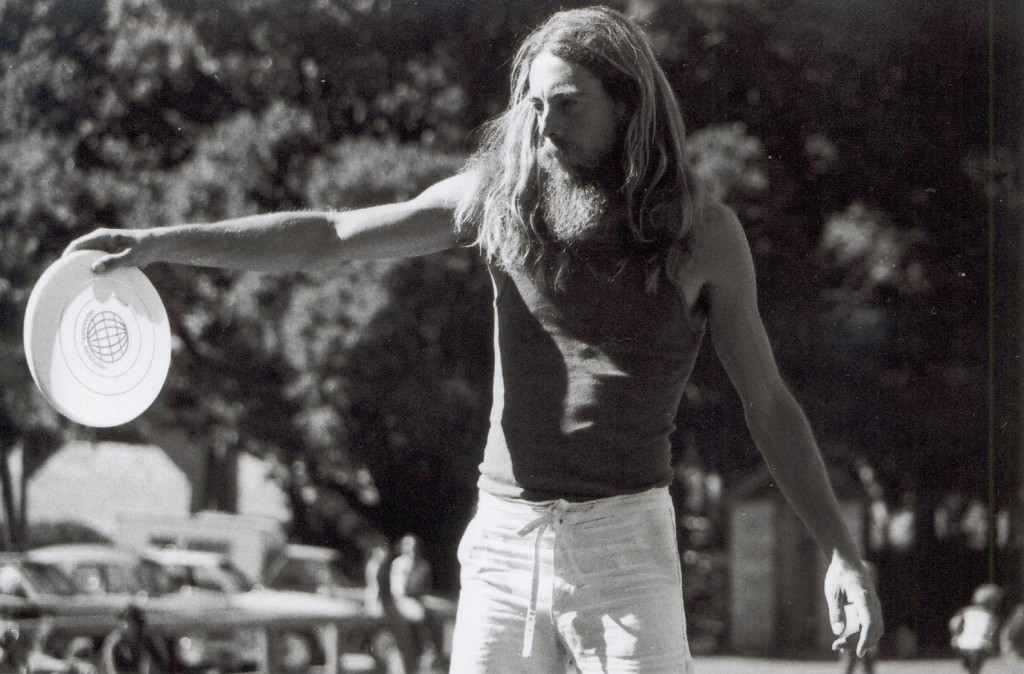

A number of TV screens play interviews with former members of the hippie movement, now in their 60s and 70s. Many are still long-haired, kaftan-wearing, placid-looking men. Their recollections vary from the fond to the bitter and are dotted with tales of mischief – but also frustration at the lives they couldn’t live. The interviews all feature the same fifteen men (very few women appear on screen) but they are helpfully edited and then bundled together in categories: music, spirituality and repression, for instance. Each section features a number of items that complement the videos, mostly photographs.

The collection does a good job at focusing on the Soviet Estonian hippie movement as a cultural phenomenon, but the historical context means politics remains inextricable from the stories behind the objects on display. This is not a criticism: one leaves the gallery with a wider understanding of the USSR – and, indeed, the West – in the 1970s, during Brezhnev’s rule.

The very concept of the exhibition raises inevitable questions about the Soviet paradox. Repression of capitalist practices and bourgeois elements can be understood in the wider context of communist ideology, but why, then, fight a movement that reflected an internationalist character similar to socialism and celebrated community life and rejection of capitalism?

The answer lies in a brilliant one-liner by one of the interviewees. “In a vacuum,” he says, grinning, “even a fart is air.” In other words, so controlled was social order in the USSR that even a young man’s shoulder-length hair constituted a subversion serious enough to warrant repercussions.

The other facet of Soviet repression of the hippies is touched upon in the “Spirituality” section of the exhibition. The Soviet ban on religion and spirituality – anything that could be considered supernatural, otherworldly or all-powerful – meant that the hippies’ attraction to figures such as members of Hare Krishna or yogis was viewed with great suspicion.

This isn’t a coincidence. A common Russian literary archetype is that of the “holy fool” – a sort of mystic agitator, often an outcast due to his or her unconventional behaviour, scandalous clothing and itinerant lifestyle. The hippies qualified for this description, and were promptly treated like fools. The Soviet state, never to shy away from its fondness for experimental psychiatry, landed many “subversive” youngsters in asylums and jails.

Indeed, perhaps the most striking part of the exhibition is the section on political repression, in which an interviewee called Peti – at the time in his late 20s – is pictured literally behind bars. The caption explains he was being held in a special clinic for venereal diseases in Tallinn, “one of the most common ways to rein in the youth of the 1970s and 1980s”. Today’s Peti happily chats from the screen directly next to the photograph. His hair and beard are just as long as they were when he was imprisoned in his hospital room.

Insanity in all its forms – faked, pretend, forced, chemically induced – is present throughout much of the exhibition. In one corner glass case containing a box of Dimedrol, a drug that has hallucinogenic powers if mixed with alcohol; the curator explains that its LSD-like effects were well known to the Estonian hippie community who frequently used it with vodka. It is now known that Dimedrol can also cause delirium, disorientation and death.

The glass case also features a book on schizophrenia, which young, pacifist hippies studied and re-enacted diligently to avoid the inevitable draft – although many were then put in Soviet asylums and became actually mad after years of experiments and forced drug-taking.

The single most interesting exhibit in the collection is perhaps a letter from one Estonian Communist youth official to his Russian counterpart, in which the former complains about groups of youngsters who have begun appearing on the streets of Tallinn and Tartu, a university town: “Their appearance – long hair, outlandish clothing- and a sloppy manner popularises degenerate Western “fashions”… In some cases [the hair] even reaches the shoulders.”

The official goes on to complain that few of the members of the hippie movement base their behaviour on philosophical grounds, which the majority “lacks the capacity to understand” due to their poor background and scarce education. (The KGB had extensive experience in tackling intellectually-driven movements; one that was mainly interested in festivals, music and what the Estonian official called “booze-ups” may well have been harder to quash.)

Whatever the actual reasons for the relative political disengagement of the majority of the hippies, it is important to remember that the movement was first and foremost a cultural phenomenon that was wholly inspired by the West.

One interviewee recalls tuning into Finnish TV and watching Hitchcock’s Psycho and reports from Woodstock; another remembers secretly listening to Janis Joplin and Jimi Hendrix on Radio Luxembourg. Music was crucial: a literal cacophony of sounds played by bands at countryside summer festivals contrasted with the sanctioned urban sounds of songs about the Soviet work ethic.

The Beatles sang about love and the Estonians responded with their own psychedelic rock, smoking dubious cigarettes with filters made out of cough medicine, wandering the country and professing the kind of spiritual freedom that the Homo Sovieticus was never to find.

From the West, the hippie movement permeated the already corroded Iron Curtain and mixed with the harsh realities of Soviet life. This gave way to some heartbreakingly naïve behaviour, such as subterfuges to avoid the draft which resulted in long stays in asylums or short-lived abstract jazz bands which succumbed to censorship. Perhaps the most extraordinary glimpse of the Estonian hippie movement is a quote by a Soviet yogi who, when asked whether politics in the USSR could ever be changed, replied: “Yes. After all, the power of the KGB is just an illusion; it’s just black magic.” If only.

Soviet Hippies ran at the Red Gallery, London EC2A 3DT, until 18/09.

Laura Gozzi is a regular writer at VolteFace. Tweets @lauragzzi