On the last Friday of September, Pastor Andrew Murray chaired an emergency community meeting in St Anne’s Church in Soho. The evening’s topic: drugs.

While merrymakers across the neighbouring West End smoked, snorted and swigged their Friday night away, Soho residents and business owners shared decidedly less glamorous stories of drug use with Pastor Murray.

Community leaders like Murray, and those who helped set up the Soho Society, have worked hard to smooth away Soho’s rough edges, the unseemly features that had, during decades past, earned the area the reputation of being somewhat sleazy. Their work has helped foster a space in the city centre where families and communities can exist in comfort, without ceding the region’s own unique brand of local colour.

However, come 2016, an ugliness had started to sweep back through the streets. The behaviour of the homeless and rough sleepers who had frequented Soho, a great deal of whom were well known and respected in their own right amongst other locals, had become uncharacteristically erratic, coinciding with the arrival of a new, particularly bullish cohort of drug dealers.

In conversation, Pastor Murray makes it clear to me that “drug crime [has been] on the obvious increase throughout 2016” in Soho. He is adamant that a new breed of dealers, peddling a new breed of drugs, are to blame for this rapid reemergence of antisocial behaviour in the area.

Several news articles published over recent months reveal this simmering drug-related disorder. Soho is likened to a scene from the ‘Walking Dead’ in The Evening Standard, and, obvious sensationalism aside, Pastor Murray confirms that conditions have become somewhat chaotic over the course of the year. Flagrant, aggressive behaviour from drug dealers, who frequently intimidate locals, have introduced ‘Spice’, synthetic cannabinoid receptor agonists (or SCRAs) to problematic drug users in Soho, the majority of whom are homeless. This has, in turn, compounded the problem as Spice is similar to cannabis in name and method of consumption only, and has proved itself highly dangerous, inducing psychotic symptoms in users. An ITV poll estimates that one in five homeless people in the borough of Westminster have consumed Spice at some point, which shows the prevalence of the toxic substance on the streets of Central London.

Reading over the minutes of September’s community meeting, the same incidents seem to surface again and again.

The hoarding of assorted drug dealers and users, openly dealing and consuming, in and amongst the great many nooks and crannies of Soho, these hideaways often including church gardens and the private alleys that back onto residential or commercial properties. Soho locals report countless incidents of aggressive behaviour: from groups refusing to be moved on to rival dealers fighting each other in broad daylight. Employees at Soho restaurants have left their jobs over this spike in anti-social behaviour, and a great many have found themselves similarly on the verge of quitting, sick of being hassled, often quite aggressively (a result of the disorientating effects of Spice), by either homeless people begging or dealers protecting their patch. The community agree that these disturbances are not the fault of local police, but are rather manifestations of the general, overriding failure to combat the intermingled societal malaise of drugs and homelessness, which their violent, Spice-fuelled resurfacing has made uncomfortably clear.

The Guardian spoke to Jamie Alexander, a former Spice user now living in a hostel:

“I call it the suicide drug: it will send you on a long, long buzz – four to five hits and you can’t move.” In a hostel in central London, James Alexander, 40, recalls trying “spice” for the first time when he was in prison.

“You get an instant buzz, you go from one to 100 straight away,” he said, shaking his head. “You get a different buzz from weed – but I don’t like it; it’s not a drug you want to be messing with. I had some the other night and the moment the buzz started I said to my mate, ‘Tear it up, put it in the bin.”

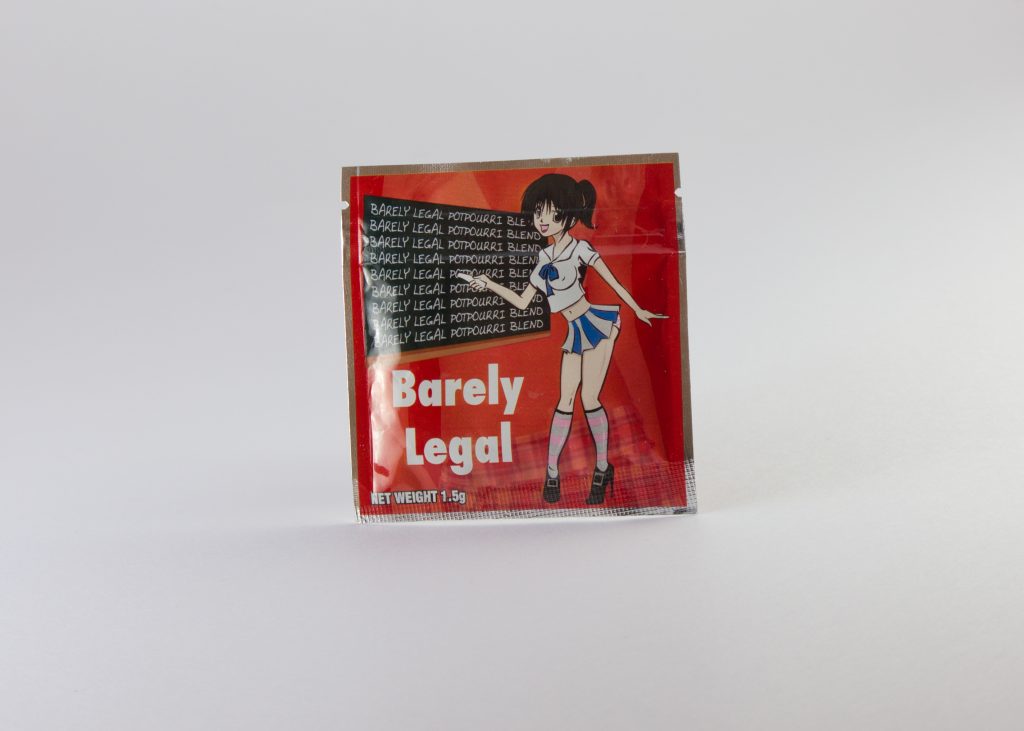

Alexander’s words show Spice for the particularly unpleasant concoction it is, which had – until the recent Psychoactive Substances Act – been available in head shops, and has now been transferred into the control of criminal gangs. Spice, which can vary in its chemical makeup and strength from batch to batch, has hijacked the cannabis ‘brand’, with manufacturers even spraying the potent SCRA chemicals onto green plant matter to create a ‘Trojan horse’ effect where its apparent similarities to the relatively safe, familiar cannabis plant are flaunted to hoodwink the undereducated and vulnerable, explaining the conviction with which dealers are pushing Spice on the homeless.

A recent BBC3 documentary – Drugs Map of Britain: Black Mamba in Wolverhampton – provides an eye-opening expansion on the worrying subject of homeless people using SCRA’s (Spice merely being the most ‘household name’ amongst these products).

Sunny Dhadley, works for SUIT, an organisation committed to helping those recovering from substance abuse issues, and is featured prominently in the programme. Dhadley shared his insights into the SCRA crisis amongst homeless people with me:

“SCRAs compound multiple issues already faced by homeless people and also adds a few new problems. The obvious health conditions associated with SCRA use affect homeless people more adversely that other parts of society. The new legal framework surrounding SCRA’s can vindicate homeless people for sharing substances between themselves in ways that was normal practice before the ban came in to force.”

Dhadley confirms my suspicions, suggesting that the recent Psychoactive Substances Act, which made SCRAs illegal, played into the hands of drug dealers, who appear to have less qualms than more legitimate retailers in forcing their product onto the vulnerable:

“The illicit marketplace does not offer a brilliant level of customer service to many of its customers, none more so than to homeless people. The attention that homeless people attract from criminal justice agencies adds an additional obstruction to the transaction process. Homeless people are becoming more and more marginalised and therefore their behaviour simply mirrors their position within society.”

SCRAs are a large component in the recent social disturbances in Soho, exacerbating as they have the already chaotic lives of problematic drug users amongst London’s homeless community. They have attracted more aggressive dealers less likely to usethe drugs the sell, and motivated purely by their own profit. They have induced a more erratic, volatile form of behaviour in their users, who, as Dhadley stresses, are being made to feel less and less welcome in the increasingly austere cities of the UK, opting thus to find an easy oblivion in the form of Spice, Black Mamba, and the other SCRA products available.

Pastor Murray shares a statement with me soon after our discussion, and it appears as if the community has found a way to curb the burgeoning chaos:

“There has been a noticeable increase in visible policing in Soho since the public meeting and some of the worst-affected locations have seen improvements. The police have also reported some successes in tackling individual offenders. However, there is still a long way to go before the community can be confident that positive change will be sustained.”

Murray is steadfast in his assertion, found in the opening lines of the meeting’s minutes, that “the drug users who are causing so much of the chaotic behaviour are people and part of the community, some of whom have been on our doorsteps for five years or more.” Soho is not going to give up on its most vulnerable, as maintained in the spirit of Murray’s words. It is however, one can ascertain at this stage, very sick of Spice.

Words by Calum Armstrong. Tweets @vf_calum