Eighty three years after Prohibition was repealed, can there be anything new to say about the ‘noble experiment’? Lisa McGirr’s new history The War on Alcohol emphatically answers that question in the affirmative.

Historians have tended to write about Prohibition as if it was doomed from the start and have therefore focused on the long campaign leading up to the 18th Amendment and the rather shorter campaign for the 21st Amendment (which abolished the prohibitionist 18th). Narrative histories of the fourteen years separating these two events fill their pages with tales of organised crime, the dubious glamour of speakeasies and the comic aspects of a doomed crusade. Since Prohibition is, it is assumed, dead for good, we can afford to laugh at the fanaticism of its adherents and marvel at the antics of bootleggers.

All entertaining stuff, but less has been said about the experience of ordinary drinkers living in Dry America for whom life was neither glamorous nor fun. This is where McGirr comes in. The title of The War on Alcohol is clearly designed to invite comparisons with the modern War on Drugs. A lesser writer might have hammered the similarities between these two disastrous follies into the ground, but McGirr is content to allow readers to make their own connections. She leaves it until the end of the book before drawing explicit parallels, of which perhaps the most significant is the disproportionate harm caused to ethnic minorities and the poor, both as suppliers and consumers, in the respective ‘wars’.

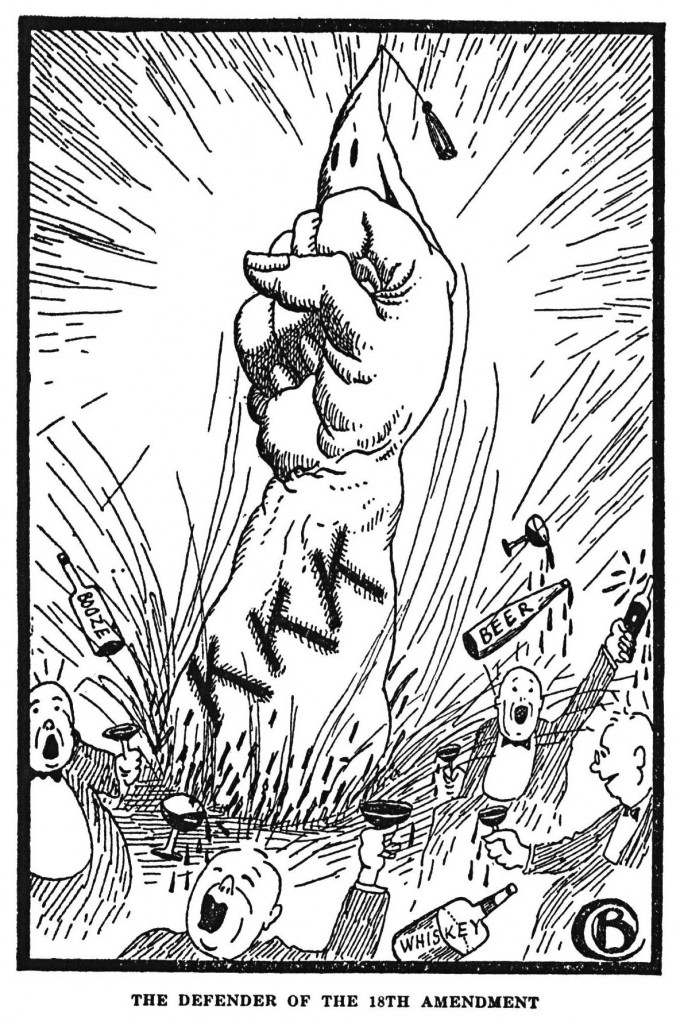

Prohibition corrupted institutions from the inside out and unleashed a wave of vigilantism that came close to a reign of terror in some towns and cities. One notable difference between Prohibition and the war on drugs is that there has never been a grassroots anti-narcotics society to compare with the formidable Anti-Saloon League. Having secured the 18th Amendment, the League effectively became an armed militia of teetotalitarians, conducting raids on private property with the tacit, and often explicit, support of local police, the Prohibition Bureau and the Women’s Christian Temperance Union. The League were true believers in the dry cause, but any mob of volunteers could join officials and private detectives in enforcing the Volstead Act. For some vigilantes, the 18th Amendment was nothing more than an excuse for persecution and score-settling. As McGirr recounts, the Ku Klux Klan enjoyed a terrifying revival once its members decided to become soldiers in the war against liquor. Unsurprisingly, some drinkers received more attention from the hooded order than others.

McGirr vividly illustrates the ways in which the 18th Amendment was used as a ‘blanket pretext to invade workers’ homes, clubs, gatherings, and boarding houses’, with detailed case studies in such localities as Chicago, New York and Pittsburgh. Much of this research is new and McGirr provides enough empirical evidence to show that the racial and class bias of Prohibition enforcement was not confined to bad apples and rotten boroughs but was a systemic, nationwide phenomenon. ‘The country is not being run for their benefit’, said the Board of Temperance, Prohibition and Public Morals when it was suggested that Prohibition was deeply unpopular with foreign-born workers. It showed.

The Klu Kux Klan took up the prohibition cause as a guise for their own racism (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

Joseph Gusfield’s classic sociological study Symbolic Crusade portrayed Prohibition as a war between WASPs and the urban proletariat. It is a view with which McGirr seems to sympathise (as do I) and it is undoubtedly true that European immigrants, blacks, Mexicans, Catholics and the urban poor were hit harder by Prohibition than cider-brewing farmers and millionaire wine collectors. Unable to afford the better quality alcohol enjoyed by the affluent, these groups were also more likely to suffer from the ill effects of cheap moonshine, which included being blinded, crippled and killed.

But it is an ill wind that blows no good. For budding entrepreneurs of any background, the illicit alcohol business was a get-rich-quick scheme. ‘The illicit liquor traffic has become a means of comparative opulence to many families that formerly were on the records of relief agencies’, reported the Federal Council of Churches in 1925. The same could be said of many drug dealers today, but the opportunities afforded to working class bootleggers were accompanied with great risks. Buyers and sellers of moonshine among the urban proletariat were much more likely to be prosecuted and imprisoned than their counterparts in high society.

The similarities between the war on alcohol and the war on drugs are striking, but they are not the core of McGirr’s thesis. Her main argument is more interesting. She contends that Prohibition led to the creation of the modern, heavy-handed American penal state. It was not, she says, a mere bump in the highway of history. It had a lasting impact not only on American drinking culture (male-dominated saloons never fully returned) but on the relationship between the American people and their government.

The First World War that preceded Prohibition and the New Deal that followed it both involved a significant expansion of government, but historians have often portrayed the period of 1920-1932 as a period of conservative retrenchment. Not so, says McGirr. The era saw the ‘greatest expansion of state building, outside of wartime, since Reconstruction’. Thanks to Prohibition and the crime wave that accompanied it, police raids on private property – including private dwellings – became commonplace, state surveillance was stepped up and the federal prison population rose threefold. By 1930, more than half of all prisoners had been convicted on drink or drug charges.

The (highly corrupt) Prohibition Bureau employed far more people and had a vastly larger budget than the Bureau of Investigation which later became the FBI under J. Edgar Hoover. Hoover watched the expansion of the Prohibition Bureau with interest and largely modelled his own organisation on it. The police, prisons and border control were all given bigger budgets to deal with the challenges of Prohibition. Government agencies, once built, rarely disband voluntarily and they had every excuse to keep growing in the 1930s. Prohibition, says McGirr, ‘permanently convinced Americans to look to the federal government for solutions to new national problems’. The war on drugs had gathered pace as the war on alcohol was burning out, providing a new stock of criminals to chase down and incarcerate.

The war on drugs grew out of Prohibition to a large extent. Certainly, it is was borne of the same strange progressive brew of optimism and authoritarianism that led Americans to believe that mankind could be remade by force of law. The drug war was, says McGirr, ‘founded on the same logic as the alcohol Prohibition regime, drew upon its core assumptions, infrastructure, and moral entrepreneurs’. Those with a better understanding of human nature correctly predicted that the market for other stimulants would grow once the market for alcohol was suppressed and McGirr makes the interesting point that the abolitionist approach to liquor influenced the Supreme Court decision in 1919 to ban non-medical addiction maintenance. It was this, as much as anything, that kick-started America’s illegal drug trade.

A further insight in McGirr’s book may come as a surprise to those who are new to this period of American history. It is easy to forget that the Republicans were once the party of black voters and city dwellers whereas the Democrats were the party of white supremacy and the countryside. This only began to change when the battle against Prohibition drove the oppressed urban workforce into the arms of Al Smith and Franklin D. Roosevelt. By giving a voice to the millions of ordinary folk who resented the dry tyranny, the Democratic party – which had not won a presidential election since 1916 – was transformed and revitalised.

One might quibble with some of McGirr’s political terminology. Her assertion that ‘neo-liberalism’ is synonymous with big government is questionable and I raised an eyebrow at her claim that Prohibition was rooted in ‘proprietary capitalism’. In truth, the politics of the Prohibition era do not easily fit modern interpretations of left and right. McGirr argues plausibly that the anti-drink crusade spawned the modern ‘Christian right’ but although they were mostly Christians, the Anti-Saloon League and WCTU were born of the Progressive era and were not right-wing as most people would understand the term. McGirr briefly mentions the WCTU’s greatest leader, Frances Willard, but only to portray her as one of the era’s many casual racists. Perhaps she was, but she was also a trade unionist, a Suffragette and a socialist. This was not an unusual combination of traits for a teetotal crusader.

US Riot Police. The Prohibition Era led to the development of far more extensive, heavy handed policing policies (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

Insofar as 21st century pigeonholes apply to pre-WWI America, the Drys were predominantly of the left whereas those who resisted the seemingly unstoppable march of progress, of which Prohibition was supposedly as a crucial part, were predominantly conservatives. If there is a political lesson to be learned from this book, it is that progressives are keen on passing laws while conservatives are keen on enforcing them. Prohibition had never been a conservative project but once the states had ratified the 18th Amendment, the likes of Herbert Hoover felt obliged to make sure the law was respected. In doing so, McGirr argues, Republicans became inclined towards ‘a kind of conservatism comfortable with a more expansive state’.

There is no shortage of books about Prohibition, many them very good (Andrew Sinclair’s The Era of Excess (1962) and Daniel Okrent’s Last Call (2010) are two personal favourites). None of them are quite like this, however. The War on Alcohol is original enough in its research and conclusions to be essential reading for any scholar of the period. Would I recommend it to someone who only intends to read one book about Prohibition? I think I would. The story is told in a broadly chronological order and all the key facts are there for those who do not know them. What sets it apart is the way it hones in on the social consequences of an extraordinary political project, the ramifications of which are still felt today.

Christopher Snowdon is an author, journalist and research fellow at the Institute of Economic Affairs. Tweets @cjsnowdon