Ask anyone who has ever tried LSD, and they will tell you that ‘paradoxical’ is a fitting descriptor of its effects. Seeing, feeling and thinking seemingly impossible scenarios are the characteristic symptoms of this and other psychedelic drugs.

On initial reading then, the title of a new study, The Paradoxical Psychological Effects of Lysergic Acid Diethylamide (LSD), published last week in Psychological Medicine, may seem to be stating a truth that has been obvious to many since the psychedelic revolution of the 1960s. However, the study, conducted by the team of the Beckley-Imperial Psychedelic Research Programme based at Imperial College London, specifically investigates the dramatically different acute and mid-term psychological effects induced by LSD in healthy volunteers, and the team’s findings are illuminating.

The acute effects of LSD — the ‘acid trip’ itself — serve as an excellent model for psychosis (hallucinations, disorientation, paranoia), yet the researchers found that the mental wellbeing of the study subjects two weeks after administering the drug was — paradoxically — positive:

“Increased optimism and trait openness were observed […] and there were no changes in delusional thinking.”

In assessing the acute effects of LSD, volunteers scored highly on a test known at the Psychomimetic States Inventory, an index of psychosis-like symptoms typically used to assess the severity of psychotic mental states.

The Beckley-Imperial team have noted some key differences between the acute experiences of the volunteers and those that would typically be expected from a genuine psychotic experience:

“Based on the PSI results, one might infer that participants’ acute LSD experiences were dominated by unpleasant psychosis-like phenomena; however, this was not the case. Some volunteers did show frank psychotic phenomena during their LSD experiences (e.g. paranoid and delusional thinking) but at the group level, positive mood was more common.”

The ability of psychedelic drugs like LSD to induce controllable psychosis-like mental states, despite not immediately sounding useful, is in itself of particular interest to researchers. It provides them with tools for probing, and hopefully treating, the underlying neurobiological mechanisms at work in patients exhibiting psychosis. Recently a team at King’s College London embarked on a study trialling treatments for schizophrenia, and the model they used to model the condition? Psilocybin, the active substance found in magic mushrooms and a psychedelic with effects similar to LSD.

However, it is the contrasting mid-term psychological effects of the drug — those lasting feelings of improved wellbeing — that hold the most promise, as far as finding a therapeutic use for LSD is concerned. The increased positive mood and thinking of the subjects that remained two weeks after they were administered the drug signify the potential of LSD as an aid to improved mental health. The hope is that in a longer-term follow up study that these lasting positive effects on mental and emotional wellbeing will remain.

The findings back up an ever-growing body of evidence that indicates the potential of psychedelic drugs, both as therapeutic aids in psychotherapy and as tools for improving the wellbeing of healthy populations. A 2015 report that looked at the collective mental health of psychedelic drug using populations found that they exhibited a lower lifetime incidence of suicidal thoughts when compared to the general population, whilst a recent study that explored the incidence of domestic abuse in an incarcerated male population found that those that had taken psychedelics were over a third less likely to have been arrested for a domestic violence offence.

Leading this new LSD study was Dr. Robin Carhart-Harris, who holds the distinction of being the first person to be given permission to legally administer LSD to healthy volunteers since it was banned internationally over 40 years ago. Whilst the specifics of the pharmacology of LSD are well understood, the challenge faced by Dr. Carhart-Harris and his team was how to join the dots between what was known to be happening at the level of neurons and receptors, to the complex and contrasting psychological effects seen in the volunteers.

The key to understanding the psychological effects lies in what the research team describe as the ‘Entropic Brain’. The team developed the Entropic Brain theory during an earlier investigation trying to understand the effects of psilocybin, and it essentially boils down to the effect that drugs like LSD and psilocybin have on a collection of neurons in the brain called the default mode network.

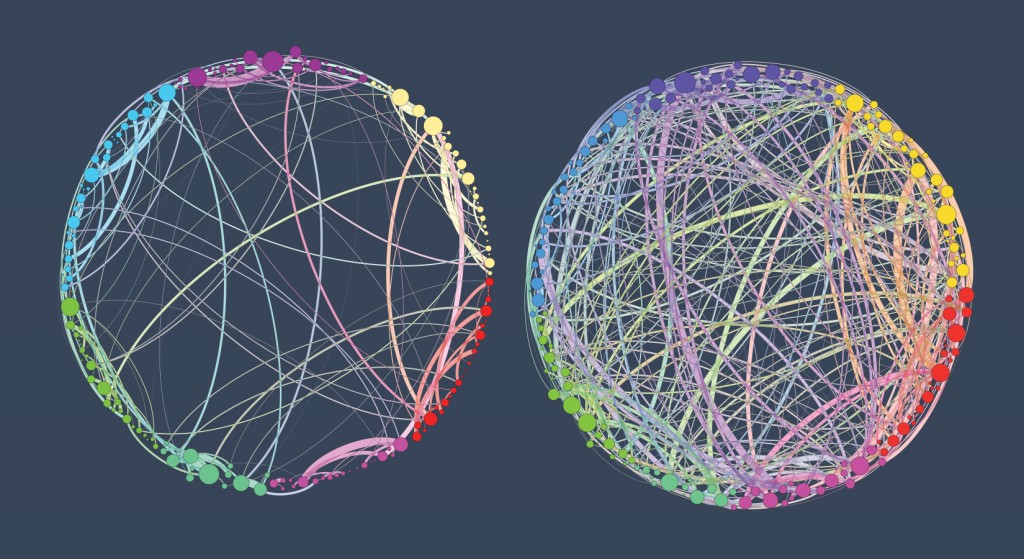

The Brain on Psilocybin: A visualisation of connectivity between functional areas in the brain during the resting state under placebo, left, and psilocybin, right. (Source: Adapted from Petri et al. 2014)

In a normally functioning brain, this network acts as a gatekeeper, or as Carhart-Harris has previously described it, “an orchestra conductor”, ensuring our mind is only focussing on one thing at a time. When under the influence of psychedelics, however, the functioning of this network is suppressed, allowing the full spectrum of thoughts and feelings to fire off at random, much like an entire orchestra playing out of time:

“The psychedelic state has been characterized as an ‘entropic’ state in which the mind/brain operates outside of its normal, optimal level of order, in a realm of relative disorder”

The short-term ‘trip’ effects of the LSD can be understood in terms of suppression of the default mode network and the resulting uncontrolled cacophony of thoughts, but it is the sustained positive effects on mood that arise after this effect has subsided that are remarkable. The team describes a subsequent resetting of thought patterns, which

“leaves a residue of ‘loosened cognition’ in the mid to long term that is conducive to improved psychological wellbeing,”

allowing more positive thought patterns to be adopted and retained.

The research constitutes part of an ongoing series of studies into the effects of LSD that is being conducted by the Beckley-Imperial Psychedelic Research Programme, an endeavour that is co-directed by Amanda Feilding, Director of the Beckley Foundation, a think tank that researches psychoactive drugs and campaigns for reform of drug policies, and Professor David Nutt, Director of the Neuropsychopharmacology Unit at Imperial College London.

The team have already released their findings on the ability of LSD to enhance people’s emotional responses to music and their emotional suggestibility, and they plan to tie all the findings together later this year with the results of a much-anticipated neuroimaging study — the first time anyone has ever imaged the human brain on LSD.

Hailing the importance of the findings, Feilding explains,

“It’s a major breakthrough, the great thing about LSD is it is very dose-sensitive. It increases wellbeing, it shakes up and breaks down rigid patterns of thinking. Out of the shake up comes new, looser patterns of thinking — and new connectivity.”

For their next steps, the team of the Beckley-Imperial Research Programme intend to pursue the potential link between psychedelics and creativity. Feilding elaborates:

“With LSD we are planning on investigating whether the increased chaos in the brain leads to greater creativity, which we hope to measure through observing changes in the pattern recognition ability of volunteers.”

Alongside the LSD study, the team have also just finished the pilot stage of a programme using psilocybin assisted psychotherapy for treatment-resistant depression. A larger clinical trial is now scheduled to take place later this year, based on promising initial results.

LSD and other psychedelic drugs clearly still have plenty of secrets to reveal, and their potential as therapeutic aids still remains largely untapped as research in the area is hampered by the regulatory and financial hurdles necessitated by their status as Schedule I drugs. With each new discovery, however, it appears science is finally allowing us to comprehend these most mysterious of psychoactive substances.